As the census of known extrasolar planets grows, so too does the variety of species in the Cosmic Planetary Zoo. There are "hot Jupiters," "super Earths," lava-covered orbs, and who knows what else — all being chased down at once. It's hard enough for professional astronomers to keep track of them all, let alone we interested bystanders.

GJ 1214b, shown in this artist's conception, is a super-Earth orbiting a red-dwarf star 40 light-years from Earth. Observations suggest that its atmosphere is mostly water.

David A. Aguilar / CfA

One exoplanet that's attracted a lot of attention since its discovery in 2009 is GJ 1214b. It circles a dim red dwarf that's just 40 light-years away in Ophiuchus, which makes this a fairly easy system to study. The planet is a "super-Earth", 2.7 times the size of ours, while the host star is only a fifth the size of our Sun and just 0.3% as luminous. The two are very close together, just 1.3 million miles (2.1 million km) apart, suggesting that the planet's surface temperature is hot but not outrageously so — probably within a couple hundred degrees of boiling water.

What makes astronomers so interested in GJ 1214b is not so much its size or proximity to us but rather its density, just 1.87 g/cm3. That's too low for it to be rocky throughout and too high to be a gas giant — but a water-rock mixture would be a good fit. In fact, follow-up spectroscopic studies with the Very Large Telescope imply that the planet's toasty-hot atmosphere is most likely dominated by water.

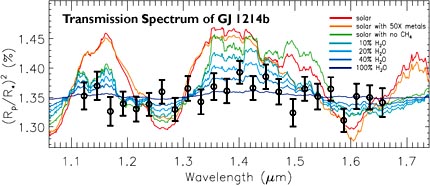

Now GJ 1214b is in the news again, thanks to near-infrared spectra collected by the Hubble Space Telescope's Wide-Field Camera 3. (WFC3 isn't a spectrometer per se, but its infrared channel has 15 different filters spaced between 1.1 and 1.7 microns.) A team led by Zachory Berta (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics) monitored three transits of the planet across the face of its host star, then carefully derived an absorption spectrum for GJ 1214b's atmosphere.

This is the first time that WFC3 has been used to monitor a transiting exoplanet, and the observers had to be alert to a few minor problems with both the instrument and the target. For example, the star itself is so cool and dim that it exhibits weak spectral features due to water molecules. Their article is set to appear in Astrophysical Journal.

Using the Hubble Space Telescope to record exoplanet GJ 1214b when it was in front of its star and off to one side, observers derived this near-infrared spectrum. Black circles (and error bars) are HST data, while the colored curves show various models for the planet's atmosphere. The new data rule out the possibility that GJ 1214b has a hydrogen-dominated atmosphere of "solar" composition or one contaminated by methane. Instead, it appears to consist mostly of water vapor.

Z. Berta & others / Astrophysical Journal

Working through these issues, Berta and his team conclude that the planet's flat infrared spectrum could not possibly be matched by a purely hydrogen atmosphere or by a hydrogen-methane mix, which had been two earlier suggestions. Nor is it likely due to a planetwide cloak of opaque clouds, which could mimic the observed spectrum but seems chemically implausible.

Instead, the new observations reinforce the notion that GJ 1214b's atmosphere contains at least 50% water by mass. This, in turn, suggests that the planet's large size and modest density are due to large amounts of water in its interior, as opposed to a rocky world surrounded by a puffed-up blanket of hydrogen and helium. And that, in turn, suggests that the planet might have formed farther out, beyond the star's "snow line," and then migrated inward to where it is now.

It's important to note that the new WFC3 measurements don't quite prove that GJ 1214b is a steam-choked waterworld, though theorists have now been boxed into a corner with no other logical outcome. The final word probably won't come until the James Webb Space Telescope or some future ground-based behemoth takes a closer look.

By the way, all morning we Sky & Telescope editors have been wrestling with a stylistic dilemma: the "b" in this planet's designation means that it's a companion to the host star — but should it be "GJ 1214b" or "GJ 1214 b"? You'll see it used both ways — there's no real consensus. As Alan MacRobert explains, "Visual binary stars have components A and B; spectroscopic binaries have components a and b. The first exoplanets were discovered spectroscopically, so they were named as if they were spectroscopic binaries. I guess it made sense at the time."

So what's your preference?

2

2

Comments

Richard Carroll

February 21, 2012 at 1:54 pm

It's bothered me for a while that exoplanets are named as if they are stars. But since an object can be discovered with no clear distinction between the two, it's probably best that the present system of "a", "b", etc. continue. However, especially as techniques improve, some pretty awkward names sound likely - suppose you have a visual binary with A and B names. If the fainter star is found to have a planet, it receives the new designation ending in -Ba, and the planet ends in -Bb. Even worse, if a planet is discovered around the fainter of a spectoscopic binary, the star ends in -ba, and the planet in -bb. We'll have to keep asking speakers if they're stuttering or not! Just kidding, it will usually be clear from the context.

Actually, I believe this situation already exists. Aren't there visual binaries where one or both stars are also spectroscopic binaries?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Edward Schaefer

February 24, 2012 at 10:25 pm

Let's see: In Star Trek, the planets had names like Rigel VI or Alpha Centauri III. So when push comes to shove, it is natural to associate a planet with its host star using an enumeration scheme. The issue is merely one of what the scheme should be. Use the Star Trek scheme? I think not or at least not yet: The numerals are in order of planets from the closest one in and heading out, and we cannot yet say that we are seeing all of the planets in any other system. Nor have we even decided what is and is not a major planet in a system.

So my suggestion is stick with what we have, and to use the space before the letter for a planet, and omit it for a stellar companion. As for a large extrasolar planet/small brown dwarf: Can you maybe use a half space? 🙂

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.