The annual Quadrantid meteor shower is expected to put on a great early morning show this weekend.

Slip into your long underwear and zip up that heavy coat. It's "pants on" for this year's Quadrantid meteor shower!

Sky & Telescope

Peaking early Saturday morning on January 4th, the annual meteoric downpour promises to be one of the year's best for North America. At maximum, the "Quads" can fire off up to 120 meteors per hour. However, the peak typically lasts just 6 hours, so unless the shower radiant is well-placed at your location near the time of maximum, you'll see a more modest display of about 25 meteors per hour.

The International Meteor Organization (IMO) puts the peak at 8:20 UT (3:20 a.m., EST) on Saturday, January 4, when the radiant in northern Boötes stands almost 40° high in the northeastern sky for observers in the eastern time zone. Further west, the radiant is lower but still above the horizon at that hour. Given that the shower will be at its best for several hours around the peak, observers all across North America should see a good show.

Obsolete But Not Dead Yet

Tycho Brahe (1598), Astronomiae instauratae mechanica

The Quadrantids emanate from the obsolete constellation, Quadrans Muralis.

Back in the 1790s, when constellation-making was still in fashion, French astronomer Joseph Jérôme de Lalande strung together several faint, unassigned stars belonging to Draco, Boötes, and Hercules, to commemorate the mural quadrant hanging on the wall of the l’École Militaire Observatory in Paris. The device was once an important tool for measuring the altitude of stars and planets as they transited the meridian.

Although the quadrant was included on several older atlases it fell out of use early int the 20th century. Only the name remains, like one of those street signs that describes a feature of the natural landscape now concealed by roads and buildings.

Viewing and Photography Tips

The first quarter Moon sets by 1:30 a.m. local time on January 4th, on the night of the shower's peak. That means the best time for a meteor watch is between 2 a.m. and dawn. As the night progresses, the radiant climbs higher and is some 60° up by the start of morning twilight.

Mike Hankey

You'll see meteors no matter which direction you face, but I usually turn 60° to 90° away from the radiant point — toward the north or southeast — to get a mix of face-on meteors, and the longer ones that streak off to the sides. Shower members always point back to the radiant, but sporadics or random meteors can come from any direction.

If you're taking pictures, remember to rubber-band two or more chemical hand warmers around the barrel of your camera lens to prevent frost or dew from forming. Use an intervalometer — a built-in camera function, or a separate hand unit that automatically trips the shutter — so you can watch the shower without having to monitor your camera. If you don't have one one already, intervelometers are easy to find on Amazon or eBay for most camera makes and models.

A good starting exposure is 30 seconds at ISO 1600 or 3200, with your lens set to f/2.8 or f/3.5. Be sure to use your camera's "live view" function to accurately focus on a bright star before you start shooting. Alternatively, you can pre-focus on the Moon earlier in the evening, then take the lens off autofocus to lock in the infinity setting.

Zombie Comet Origin

Peter Jenniskens with visualization by Ian Webster

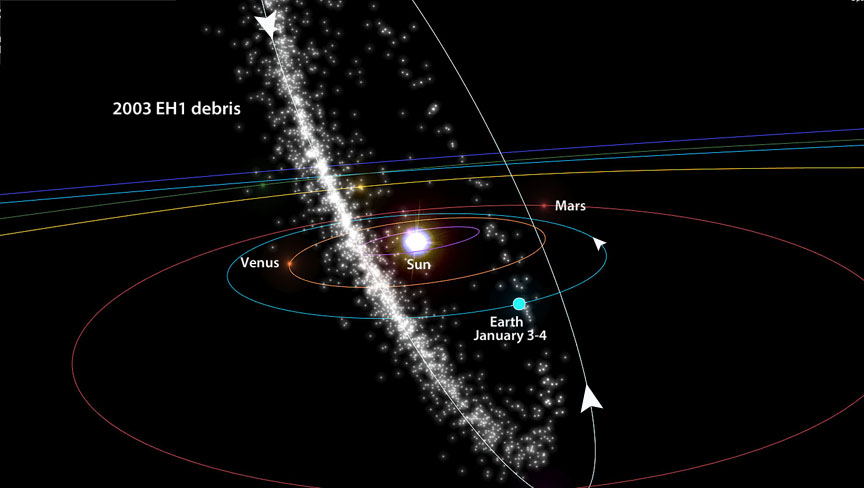

When a Quadrantid flares across the sky, you're seeing a flake from an extinct, near-Earth comet cataloged as 2003 EH1. Discovered in 2003, the object is thought to be the remnant of a much larger comet that broke up long ago. Because the debris stream is narrow, and Earth encounters it perpendicularly, our planet flies through the densest strands of meteoroid dust in just a matter of hours, which is why the peak is so brief. Don't miss it!

4

4

Comments

Anthony Barreiro

January 4, 2020 at 3:55 pm

About 0615 PST yesterday morning, January 3, about 70 minutes before sunrise, I happened to see a bright meteor streaking downward toward the northeast, south of Vega. I think it might have been a Quadrantid, but it might have been a sporadic. Last night and this morning were cloudy, so no more Quadrantids for me.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

January 6, 2020 at 10:53 am

Anthony,

Glad you saw something! I was so disappointed. Clear skies were predicted but didn't materialize.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Anthony Barreiro

January 6, 2020 at 3:23 pm

Oh, I'm sorry. I saw two more before dawn yesterday morning, January 5 -- one near Vega and the other near Deneb, both seemed to be on the right apparent trajectory to be Quadrantids. I don't really try to see meteors here in the city, but I'm always happy when I do see one.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Chuck Hards

January 6, 2020 at 1:20 pm

I went out from 1AM to 2AM when the sky miraculously cleared enough to see some stars. Still a high, very thin cirrus but I gave it a go. I saw exactly one Quad. Short, fast, bright, cutting through Leo.

At least I saw one, I've been completely skunked on meteor showers in the past. Seeing just the one made the hour worthwhile.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.