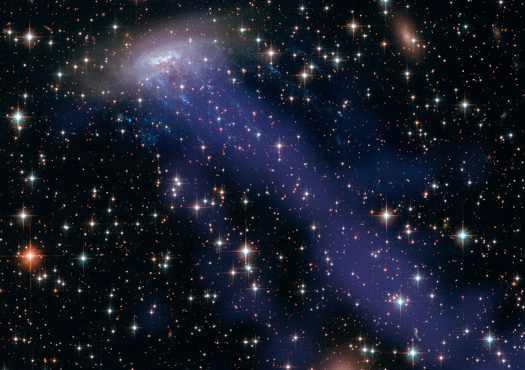

These stunning new images of spiral galaxy ESO 137-001 highlight its violent encounter with the intracluster plasma of Abell 3627, which is stripping away its gas and forming stars in the streamers.

NASA/ESA

This new image from the Hubble Space Telescope shows the galaxy ESO 137-001, located in the Abell 3627 cluster in the Triangulum Australe. This spiral galaxy may look like a jellyfish casually trailing tentacles through space, but don’t be fooled by its serene appearance. ESO 137-001 is being violently stripped of its gas and dust as it plows through the hot, diffuse gas filling the cluster. The interaction is forming new blue stars in the stripped streamers.

NASA/ESA/CXC

This "ram pressure stripping" shows up better in the second image, which is a composite of Hubble and Chandra X-ray Observatory images. Most of the gas is only visible in the X-ray part of the spectrum (shown blue).

Ram pressure is the pressure exerted on something moving through a fluid, such as water or air. This pressure creates drag. So essentially, ESO 137-001 is experiencing an immense drag as it moves through the gas permeating the galaxy cluster. The ram pressure in this intracluster medium is strong enough to strips off gas from the galaxy. It’s like when you use a hair dryer on full blast and it splays hairs away from your head—it’ll even launch hairs that aren’t strongly attached away into the air. Except in this case, gas are being pushed “off” a galaxy.

Stars are too tiny (relatively speaking) and massive to be affected. But the gas in the streamers is turbulent, and parts of it become compressed enough to trigger the gravitational collapse of small cloudlets, which then form bright new stars.

Meanwhile, the stripping renders the victim galaxy unable to form new stars itself once its gas is gone.

Another fascinating example of the strange things that can happen to stars because of ram pressure stripping is that of IC 3418, a galaxy in the Virgo Cluster, whose gas tails may harbor one of the most distant individual stars ever seen. The effect might also explain why our Milky Way does not have more dwarf satellite galaxies visible.

Read the full press release from Hubble and the European Space Agency.

5

5

Comments

Bruce Mayfield

March 11, 2014 at 5:38 am

I've enjoyed your writing Emily, but in this report I must question some of your statements. Ram pressure stripping is clearly pushing lite weight gas and dust out of the pictured galaxy, but can gas pressure really be powerful enough to strip stars out too? It hardly seems possible that objects as massive as stars could be essentially blown out of a galaxy by an intergalactic wind. There likely are stars forming in the compressed gas steams, which makes it look like stars are being torn out, but the gas gets stripped first and then would be illuminated by new star formation inside the stripped gas and dust, IMO.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

tom hoffelder

March 11, 2014 at 7:44 pm

I guess it is just me, but EVERY time I see a photo like this two questions immediately pop into my head: 1) What is the field of view and 2) How far away is the main subject? Then I read the associated article, and as usual, my questions are not answered. At least now that I'm retired I have time to try to find the answers. The distance is easy since it is noted in the "full press release" as around 200 million ly. The FOV took a little more work, but based on a fuzzy 2.4'x2.4' photo on SIMBAD, the photo at the top of this article covers about 1.5x2.5 arc minutes, in case anyone else wonders these things. Back to the full press release, WOW, I thought NASA was bad at creating sensationalistic titles for astronomy articles. ESA has pulled ahead in that race! Also that article says, "These streaks are actually hot young stars, encased in wispy streams of gas that are being torn away from the galaxy..." It's hard to tell from that whether the stars were ripped from the galaxy with the gas or if they formed in the gas after it was ripped. My guess would be the latter, but it's only a guess.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Alan MacRobert

March 12, 2014 at 9:03 am

> can gas pressure really be powerful enough to strip stars out too?

No, that was a mistake. It's fixed now. Thanks for catching this!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Peter

March 14, 2014 at 2:00 pm

Why is there no star formation on the leading side, where gas compression/density would be expected to be highest?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bruce Mayfield

March 14, 2014 at 6:47 pm

Peter, there most likely would have been the beginnings of star formation on the leading side of ESO 137-001 when this galaxy first began its motion into the intergalactic headwind, but by now the leading side must surely have been swept clean of all star making materials. The stars that formed first might be among those lighting up the “tendrils” farthest from the galaxy now. But how long would it have taken the pressure front to have lit up with new stars? The galactic motion of 137-001’s gas and dust would be halted by the ram pressure while the galaxies massive bodies like previously formed stars keep right on trucking with the galaxy’s overall motion. Did these new stars that are trailing behind the galaxy form while still inside the galaxy proper? So yeah, these new stars weren’t blown out of the galaxy technically, but some of them could have still been inside the galaxy when they formed. Alan MacRobert, I sure hope that my pointing out a technicality hasn’t hurt the promising career of a fine young science writer. I hope to soon read more reports with Emily Poore’s byline. The fact that she herself didn’t respond but one of her superiors did gives me pause.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.