NASA's Magnetospheric Multiscale (MMS) mission will study the behavior of magnetic fields around Earth.

Credit: NASA

It’s the mission you might never have heard of. Even the name might leave you scratching your head. But with the goal of better understanding Earth’s space weather environment, NASA’s Magnetospheric Multiscale (MMS) mission launched just over an hour before midnight on March 12th from Cape Canaveral on a worthwhile endeavor.

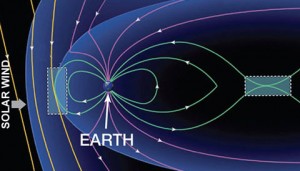

The mission aims to provide a high-resolution, 3D view of magnetic reconnection in Earth’s magnetosphere, the magnetic windsock that surrounds our planet and where Earth’s magnetic field wins out over the solar magnetic field streaming by. Reconnection is the rapid-fire splicing of magnetic field lines, essentially a magnetic explosion that releases billions of megatons of TNT’s worth of energy. When Earth’s field lines reconnect, they can shoot back toward Earth and hurl charged particles into our atmosphere, spurring auroras. It’s also the process by which the Sun unleashes massive flares.

MMS isn't the first mission to investigate goings-on in the magnetosphere. Other notable missions include ESA's Cluster and NASA's THEMIS. But MMS mission scientists aim to do measurements 100 times faster than before.

MMS is a quartet of four, 11-foot-wide octagons each decked out with 11 instruments. Once in space they’ll unfurl various booms, including wire booms nearly 200 feet long with sensors on the ends, making them look a bit hairy. In terms of magnetic and electric fields, the spacecraft are some of the cleanest ever launched: they need to prevent as much residual magnetism and electric charge as possible, in order to detect with high precision what’s happening with the charged particles and magnetic fields in Earth’s vicinity.

The four spacecraft will fly 10 kilometers apart, and they must maintain their tetrahedron formation to an accuracy of 100 meters, or one-hundredth that distance. The nominal mission is two years, with six months prior to that spent moving them into orbit. They won’t predict space weather directly, but their data will help scientists better understand how that weather works.

Reconnection also happens closer to home, in lab devices designed to harness nuclear fusion, principal investigator Jim Burch (Southwest Research Institute, San Antonio) pointed out in a prelaunch press conference held on February 25th. So-called sawtooth crashes are a current topic of investigation for plasma physicists, and MMS data might help them understand how magnetic reconnection works in their systems, too, Burch said.

Check out NASA’s press release on the launch for more info on MMS. Below, you’ll also find two videos. The first is a video of magnetic reconnection in Earth’s magnetosphere caused when a coronal mass ejection from the Sun disrupted the magnetosphere and triggered a geomagnetic storm in July 2012. (The reconnection is the rapid bottlenecking and shrinking of the loops on the right-hand side, Earth’s night side.) The second is a crash course from MMS team member Paul Cassak (University of West Virginia) on how magnetic reconnection works. (If you prefer computer graphics to chalkboard diagrams, you can also watch another video from NASA. The MMS folks also have several other educational videos.)

Credit: NASA / CCMC / Bridgman

Credit: NASA Goddard Science, sponsored by CLUSTER II and MMS Mission Education & Public

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.