The events that occurred in northwestern Canada on January 18, 2000 — and in the critical days thereafter — might just be the most important ever in the science of meteoritics. That's when a 50-ton chunk of interplanetary debris exploded in the early-morning sky, rattling the residents below and dropping dark meteorites onto the frozen, snow-covered terrain near the provincial capital of Whitehorse.

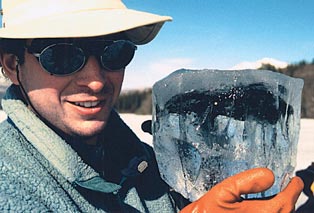

This piece from the Tagish Lake meteorite fall in January 2000, seen here still encased in a chunk of ice, represents one of the oldest — and most pristine — samples of the early solar system on Earth.

Alan Hildebrand (University of Calgary)

Within days of the fall, an alert local outdoorsman named Jim Brook had carefully collected nearly a kilogram of still-frozen fragments in clean plastic bags and stashed them in his freezer. Later a team of Canadian geologists and volunteers scoured the lake's frozen surface to collect as much of the fragile interplanetary material as possible (even using chain saws to hack some pieces out of the ice) before the spring thaw swallowed up the remaining pieces.

Remarkable as much for the rapid, textbook recovery effort as for the stones' black, carbon-rich texture, the Tagish Lake fall has provided cosmic chemists with a unique window into the materials forged at the very beginning of the solar system.

From the outset, however, researchers were puzzled by what they found inside the frozen stones. In some cases, the dark, crumbly interiors (having the highest carbon content of any meteorite) are riddled with carbonate minerals created when liquid water percolated through the rock multiple times. Yet adjacent sections bear no carbonates or other traces of water's influence at all.

The dark interior of this 157-gram piece of Tagish Lake meteorite reveals stone's carbon-rich composition. The small cube to its left is 1 cm on a side.

NASA / Mike Zolensky

Although chemists would have bet money that the black stones teemed with exotic hydrocarbon compounds, analyses turned up a disappointing yield. "We were hoping to find all these amino acids," lamented Iain Gilmour (Open University) after his team's initial tests, "and they're just not there."

But researchers are still ever-so-thankful that Jim Brook happened along so soon after that fateful February day. By having access to the meteorite in an uncontaminated, still-frozen state, a new round of research shows that Tagish Lake has helped solve a longstanding puzzle about the origin of organic material found in primitive objects throughout the solar system.

In the June 10th issue of Science, a team led by Christopher Herd (University of Alberta) reports that various amino acids are present in four carefully analyzed Tagish Lake samples at only a few parts per million, with many undetectable at even 1 part per billion. Instead, much of the organic content is in the form of monocarboxylic acids, or MCAs, the types of which showed wide variations from stone to stone.

Rather than being due to differing primeval mixtures, Herd's team believes that this diverse organic menu was cooked up within the meteorite's parent body, influenced solely by how much the compounds were exposed to liquid water and to modest heat (no higher than 240°F) from rapid-decaying radioisotopes such as aluminum-26.

"What we're saying is that amino acids are actually the result of the geology happening on the asteroid," Herd told the Canadian Broadcast Centre. Moreover, the water and warmth present in the parent asteroid's interior — not to mention the shielding it provided from space radiation — likely provided better conditions for chemical synthesis than would exist in interstellar space.

As noted in an online press release, the high-end, "insoluble" organic matter found in the samples (such as amino acids, essential for forming proteins) maps well to nearly the entire compositional range found in primitive meteorites. It gives credence to the idea that the solar system's organics came from a common source, and that Earth likely got its fair share as our young planet swept up countless asteroids and comets.

You'll enjoy listening to an interview with Herd on this week's "Quirks and Quarks," a CBC radio program hosted by award-winning science reporter Bob McDonald.

4

4

Comments

Geoff

June 10, 2011 at 9:25 pm

Kelly,

Quoted in your interesting article Iain Gilmour says this about amino acids: "...they're just not there."

But Christopher Herd says they did find amino acids. Who is right? I looked at Herd's Science press release, and it says nothing about the handedness of the amino acids (life forms on Earth use only left-handed amino acids). Any comments?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Kelly Beatty

June 12, 2011 at 8:05 am

Geoff: Herd's team reports in Science that amino acids truly are in short supply (a few ppm at best). I've changed the wording to make this clearer. Also, the chirality, or "handedness", of the organic molecules was largely racemic (equal amounts), with a slight L excess in isovaline. Thanks!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

sam

June 14, 2011 at 6:31 am

The small debris meteorite, while entering the Mesosphere, of the earth’s atmosphere over the earth 70 to 100 Km height, with 15 to 30 Km per second speed, it will reach 3000 degree Celsius. So, everything melts in the small body, and the Amino Acids will evaporate Due to high temperature in the small meteorite body, How is it possible to find the Amino Acids and organisms in his small debris?

Sam.G

Space Research Center of Madras

India

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Michael C. Emmert

June 30, 2011 at 3:10 pm

Hello, Sam, when a meteor flies through the atmosphere, it is almost all air that is heated by it's passage. The meteor will slow down very quickly, hundreds or thousands of g's deceleration, and there's little time for the heat to penetrate. It is protected by ablation, which only affects the skin.

Tagish Lake is a stunning find that teaches us a lot about the Solar system. I have been waiting for this article and was not disappointed. My thanks to Jim Brook and his extended team for a job well done.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.