Using data from the Gaia satellite, astronomers have dissected the dance of our galactic neighbors, finding a host of insights into how galaxies in the Local Group evolve and interact.

Astronomers have used the European Space Agency’s Gaia satellite to measure the rotation on the plane of the sky for the Andromeda and Triangulum galaxies – the largest galaxies in the Local Group outside of the Milky Way. The results have some surprising implications for our future — in 4.5 billion years or so.

“We know galaxies rotate,” says Roeland van der Marel (Space Telescope Science Institute), who led a team in publishing the results in The Astrophysical Journal. But, he adds, this rotation has never been measured in three dimensions and on the level of individual stars. “But with less than two years of Gaia data, we were able to measure the 250 million-year revolution of Andromeda.” To put this in perspective, van der Marel says, the stars that Gaia was staring at move at the same speed that a human hair would grow as seen at the distance of the Moon.

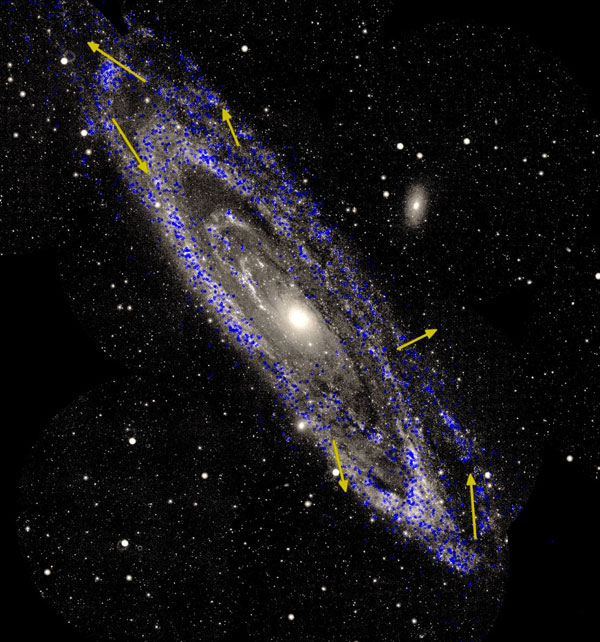

To understand the galaxies’ current motions, the researchers used the second data release from the Gaia satellite – which provides accurate distance measurements to an astonishing 1.7 billion stars. The researchers averaged the motions of 1,084 and 1,518 stars in Andromeda and Triangulum, respectively, to calculate both galaxies’ rotation, as well as their motion across the sky.

Star motions: ESA / Gaia; Background image: NASA / Galex; R. van der Marel / M. Fardal / J. Sahlmann (STScI)

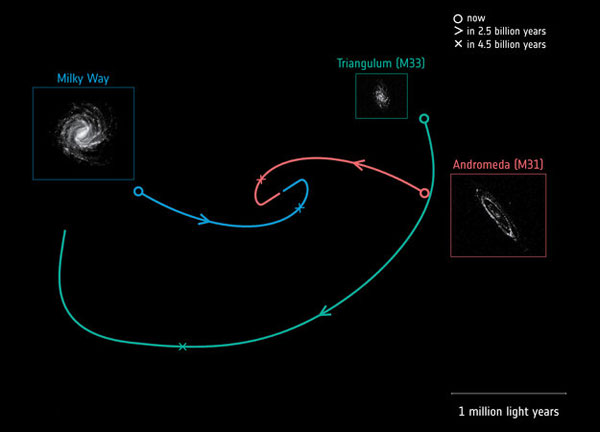

The team then simulated past and future movement of Local Group galaxies across the sky, looking billions of years backward and forward in time. The projections allowed them to answer two central questions about the Local Group.

When Did the Local Group Come Together?

Both the Milky Way and Andromeda have satellite galaxies that are roughly 1/10th their mass – the Large Magellanic Cloud and the Triangulum Galaxy, respectively. It was previously thought that these satellites had been long-term companions of their bigger cousins. However, more recent work has revealed that the Large Magellanic Cloud is falling into our galaxy for the very first time. It’s a long fall — the two won’t merge for about another 2.5 billion years.

Sharp images from the Hubble Space Telescope and radio data from the Very Long Baseline Array had suggested that Andromeda and Triangulum might have had a different history: passing close by each other 6 billion years ago and are doing so again currently.

But the new simulations reveal that this scenario cannot be true — Triangulum is only now making its first approach. Essentially, this result suggests that the Local Group came together more recently than previously thought – and it’s still growing today.

Orbits: E. Patel / G. Besla (Univ. of Arizona) / R. van der Marel (STScI); Images: ESA (Milky Way); ESA / Gaia / DPAC (M31, M33)

At a broader level, the result adds to evidence that galactic interactions are much more dynamic than anticipated. “It’s much less likely that a galaxy will have a companion that just hangs around for billions and billions of years, without merging,” says van der Marel. Instead, merging is common and happens relatively fast.

When Will the Milky Way and Andromeda Galaxies Meet?

The team’s analysis also found that the Milky Way meet-up with Andromeda won’t play out the way we once thought. Astronomers have long known that Andromeda is barrelling towards us at about 110 km/s. But what has been harder to gauge is how fast our sister galaxy is moving sideways. A large sideways motion could even have Andromeda miss the Milky Way completely.

Van der Marel called the Hubble Space Telescope into action in 2012 to answer this question. Hubble data suggested that there was only a small sideways motion (about 17 km/s), so the two galaxies were heading for a head-on collision. But now, after averaging the Hubble results with the new Gaia measurements, van der Marel’s team finds that Andromeda is sliding sideways more quickly, at around 60 km/s. “That means the orbit [of the two galaxies] will be more of a glancing blow than a head-on collision,” he says. “But it’s still very much the case that these two galaxies will ultimately collide.”

S.T. Sohn & others / ApJ

The new result revises the predicted date of the galactic merger from 3.9 billion years’ time to 4.5 billion. By then, the Earth will be twice its current age and completely uninhabitable. But there is a slim chance our distant descendants might visit their former home to watch what will undoubtedly be the greatest lightshow in the history of our corner of the universe.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.