If you're a regular reader of our news stories, you know that astronomers have struggled for decades to understand what's going on with the binary star Epsilon Aurigae. This easy naked-eye star, now high overhead after dusk, was discovered to dim in 1821. By a half century ago it was generally recognized as some kind of eclipsing system with a period of 27.1 years.

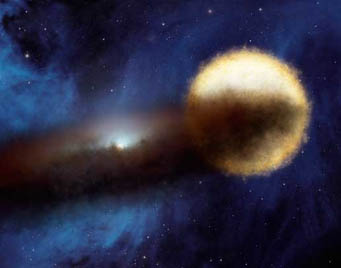

In this artist's concept, Epsilon Aurigae (the supergiant F star at right) is starting to be eclipsed by the dust disk circling a single, much dimmer (but more massive) B star.

NASA / JPL

In other eclipsing binaries, it usually takes only hours or at days for one star to cross in front of the other. But Epsilon Aurigae's partial eclipses take two years to complete — and the most recent began last August. Stellar theorists have struggled mightily to deduce what's causing such long dimmings. The American Association of Variable Star Observers even launched a grassroots effort to have "citizen-scientists" help keep track of the system's antics.

Epsilon Aurigae's central star is a F-type giant pumping out 130,000 times the Sun's brightness. That much now seems clear. But there have been at least five candidate explanations for the eclipsing component: (1) a huge, nearly spherical nebula that's somewhat opaque; (2) a massive, dark disk of gas and dust; (3) a black hole cocooned inside a disk; (4) a thin, tipped disk with a binary star at its center; and (5) a large, slightly tilted disk surrounding a single hot B star. As S&T editor-in-chief Bob Naeye described a few months ago, this last scenario has gained favor recently.

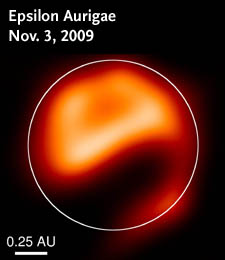

New observations of Epsilon Aurigae, just announced in the April 8th issue of Nature, show that the Answer Number 5 is likely correct. University of Denver graduate student Brian Kloppenborg and advisor Robert Stencel led an international team that resolved the eclipsing body crossing the bright star's face for the first time. Using the Center for High-Resolution Astronomy's six-telescope interferometer arrayed on Mount Wilson in California, the astronomers synthesized images last November and December showing the leading edge of an elongated dark mass moving across the bright star.

A dark finger of dust extends across the disk of Epsilon Aurigae's central star, resolved for the first time by an interferometric array of telescopes atop Mount Wilson and the Michigan Infrared beam Combiner.

John D. Monnier / Univ. of Michigan

By carefully combining individual light waves from its telescopes, the CHARA array can approach the resolving power of a single telescope 1,100 feet (330 m) across. It's capable of resolving details 0.0002 arcsecond apart — the angular size of a small coin seen from a distance of 10,000 miles (15,000 km).

Based on the images, Kloppenborg, Stencel, and the others calculate that the dark disk is about a billion miles (1½ billion km) wide — roughly the size of Jupiter's orbit — but appears only a fifth as tall. However, the new images haven't completely cleared up Epsilon Aurigae's mysteries. Yet-to-be-published work by Robin Leadbetter (Three Hills Observatory) and Stencel argues that the disk's detailed shape doesn't fit any of the models exactly. But most of the current eclipse has yet to occur, so many observations are still to come.

In the meantime, read more about the remarkable new images in this National Science Foundation press release. "Dr. Bob" Stencel has put together a nice slide show about CHARA and the team, and the University of Michigan (whose "combiner" created the images) has posted an animation showing how the eclipse is progressing.

Members of the Helena Hotshots pause for a group shot in front of the CHARA building atop Mount Wilson. Click on the image to see the full team, along with observatory director Hal McAlister at far left and team leader Fred Thompson at far right.

David Jurasevich

You can even chat with Kloppenborg and "Dr. Bob" on Friday, April 9th, via the Global Astronomy Month website.

Finally, consider this: The CHARA observations wouldn't have been possible had the catastrophic Station Fire overrun the summit of Mount Wilson last September. So I hope someone sends a copy of the Nature article to the firefighters of the Helena Hotshots, who were key to saving the array and the other telescopes atop the mountain.

2

2

Comments

Dan

April 18, 2010 at 11:03 pm

Given the estimated size, could this be a solar system that failed?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Jeff Hopkins

April 28, 2010 at 12:19 pm

The Epsilon Aurigae Campaign has just published Newsletter #17. It is available as a free pdf file on the Campaign web site. Included are composite photometric plots that show a most interesting ingress and start of totality. There is also a report on spectroscopic observations. See the Campaign web site at http://www.hposoft.com/Campaign09.html or download the Newsletter directly at http://www.hposoft.com/EAur09/NL09/NL17.pdf

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.