It's been a busy couple of weeks for astronomers who like to watch stars explode.

An engraving from Camille Flammarion's Astronomie Populaire (1880) depicts Tycho Brahe's sighting of the supernova (upper left) near the familiar "M" of Cassiopeia on November 11, 1572. Click on the image for a larger version.

D. Olson / M. Olson / R. Doescher

Just last week, a pair of researchers floated the idea that a nearby supernova, the one responsible for creating the dramatic Cas A remnant, could have heralded a royal birth. British astronomer Martin Lunn and American historian Lila Rakoczy argue that a star blazed forth about the time of Charles II's birth on May 29, 1630. It's a controversial claim, because there are no definitive astronomical records chronicling the appearance of what should have been a whopping-bright "guest star" in Cassiopeia.

There's no such ambiguity concerning the supernova of 1572, which Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe studied intently. In his publication Astronomiae instauratae progymnasmata, Brahe writes that during an after-dinner stroll on November 11th that year, "I suddenly and unexpectedly beheld near the zenith an unaccustomed star with a bright radiant light." He goes on to describe how it rivaled Venus (magnitude -4.6 at the time) and how sharp-eyed "country folk" could spot it in the daytime sky. And as Donald Olson and others detailed in Sky & Telescope's November 1998 issue, the cosmic visage might have been the inspiration for several star-themed lines in Shakespeare's Hamlet.

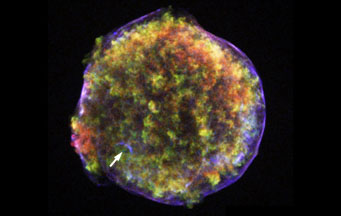

An subtle arc of X-ray emission (arrowed) in the Tycho supernova remnant provides evidence for what triggered the original explosion.

NASA / CXC / Chinese Academy of Sciences / F. Lu & others

But while Tycho's Supernova itself couldn't be examined telescopically, modern astronomers have probed its ever-expanding remnant in the hope of determining what triggered the event. They know such spectacles occur either when a single massive star becomes unstable and collapses on itself (a Type II event) or when a white dwarf accumulates too much matter from a close companion and spontaneously self-destructs (Type Ia).

For the past decade, there's been general consensus that the latter scenario was in play when a blast of starlight lit up Tycho's sky. The silicon, sodium, iron, and other elements in the remnant's spectrum argue strongly for a two-star solution.

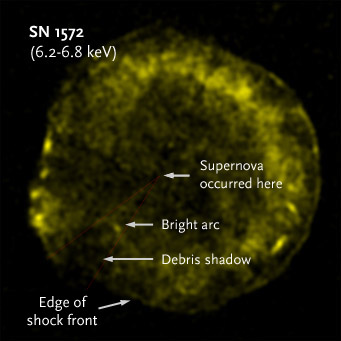

When viewed in iron's X-ray emission from 6.2 to 6.8 keV, the bright arc and its shadow are situated "downwind" from the supernova's presumed companion.

NASA / CXC / Chinese Academy of Sciences / F. Lu & others

Yet uncertainty remained: had a white dwarf sucked matter off a nearby donor before blowing itself to smithereens, or had two white dwarfs collided? In 2004, using both ground-based telescopes and the Hubble Space Telescope, Pilar Ruiz-Lapuente (University of Barcelona) identified the purported companion at the center of the Cas A remnant. Tycho G, as he called it, is a solar-type star slightly offset from the remnant's center. But it wasn't a slam-dunk identification, and the search for the supernova's origins continued.

Now new evidence has emerged from observations made with NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory that Tycho G might well have survived the blast — but took a big hit. In an article appearing in May 1st's Astrophysical Journal, Fangjun Lu (Institute of High Energy Physics, Beijing) describes a bright arc of material that's aligned with Tycho G's position but farther from the remnant's center. The arc appears in earlier Chandra images, but astronomers assumed it was simply part of the expanding shock front that appeared near the center due to projection.

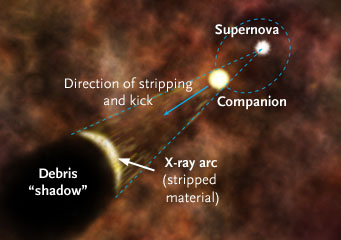

This artist's impression (not to scale) depicts how an X-ray arc seen in Tycho's supernova remnant could have formed from as material was stripped off a companion star by the explosion of a white dwarf. The arc creates a "shadow" where debris is shielded from the expanding shock wave.

NASA / CXC / M.Weiss

Lu's team, however, believes the glowing arc represents a Jupiter's worth of material blown off the companion star by the titanic blast. He points out that the glowing crescent creates what seems to be a shadow on debris lying farther away. "We found that it is actually in the interior of the remnant," he says, "and is most probably due to the interaction between the stripped companion envelope and the supernova explosion." Moreover, Tycho G's motion seems to have been redirected by a swift kick from the supernova blast.

"I think the circumstantial evidence of Lu et al. is very interesting," comments David Branch, an expert in Type Ia supernovae at the University of Oklahoma. "However, things work out nicely only if star G was the donor" — and there's a school of thought that it's not. "We need more observations of both the Lu arc and the candidate donor stars," Branch offers, "before we can get to the bottom of this."

3

3

Comments

Peter Wilson

May 3, 2011 at 6:43 am

There are a lot of bright arcs and dark patches in the photo. I'm just saying, a Type II event will leave a neutron star or black hole. If the the purported companion at the center of the Cas A remnant is orbiting something, or not, wouldn't that settle the two-star question definitively?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Spacermike

May 4, 2011 at 8:41 am

Why no reports of Tyco's supernova is exactly as it is today. Guys like me who naked eye view the heavens every night and see events try to report them and get ignored. For example Ursa Major had some major event back in January 2011 almost dead centre of the big dipper's bucket. I could noteven get a pro to confirm it. Isn't it about time we have a focal point that responds to amateur sightings?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Frank R.

May 6, 2011 at 7:32 pm

Spacermike, you wrote:

"For example Ursa Major had some major event back in January 2011 almost dead centre of the big dipper's bucket."

What do you mean? A bright temporary star visible for less than a minute? Like a very brief "nova"? If so, then you probably saw a flare from a high-altitude satellite. Flares from low-altitude Iridium satellites are famous because they are very bright and so predictable, but many other satellites will flare to startling brilliance at unexpected moments.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.