After a century, researchers may finally have solved a prehistoric meteorite mystery.

NASA

Imagine the scene: One fine day, about 790,000 years ago in the late Pleistocene, an asteroid 2 km (1.2 miles) across split the sky over modern-day Southeast Asia. The gigantic space rock came in at a shallow angle, gouging out a crater 17 km (10.6 miles) wide and showering the surrounding region with debris. While the impactor was 30 times smaller than the one that caused the Chicxulub extinction event 65 million years ago, it was 100 times bigger than the more recent bolide that exploded over Chelyabinsk, Russia, in 2013.

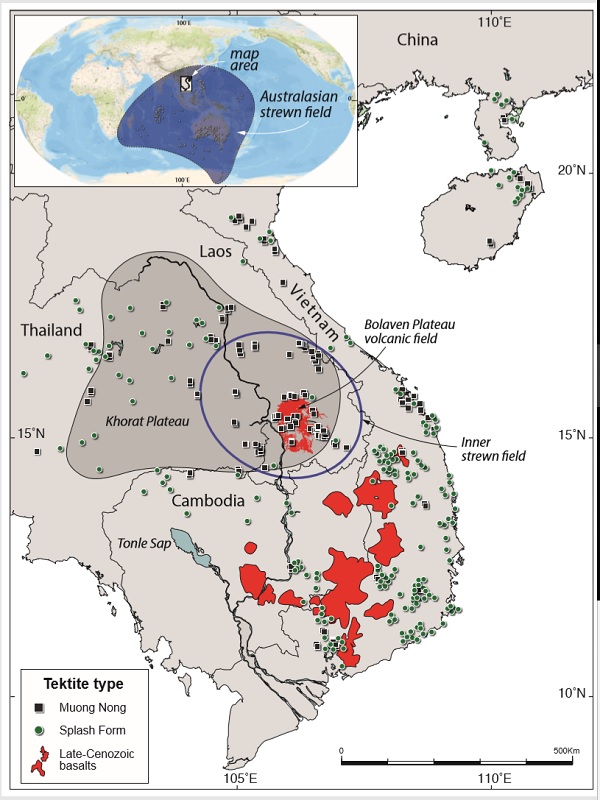

Nevertheless, while the impact was not on the level to cause an extinction event, it was significant enough to have left a sizeable crater. But there was no obvious crater in sight. All geologists had to go off of were a multitude of molten-glass fragments called tektites, which rained down all across the Indian Ocean, Australia,and Southeast Asia after the impact. Many of these glass beads take on a teardrop shape, known as splash-form tektites (see image below). Others take on an ablated "pancake" form after cooling.

Dayana Schonwalder

This region where tektites are found is known as the Australasian tektite strewnfield. It's the largest of its kind, covering a tenth of the planet’s surface; some of these tektites have even been found as far away as the coast of Antarctica.

Yet despite the preponderance of these signs of an ancient impact, the location of the crater from which these fragments were thrown out has long remained a mystery — despite more than a century of searching. Previous claims had resorted to suggesting that multiple craters could be responsible, some as distant as Kazakhstan.

Now, researchers think they've found the crater responsible buried under the Bolaven Plateau, a sandstone and mudstone upland in southeastern Laos that's covered in dried lava up to 300 meters (1,000 feet) thick.

Kerry Sieh / Earth Observatory Singapore

The proposed Bolaven impact “is likely the largest crater (on Earth) formed within the past million years,” says study lead Kerry Sieh (Earth Observatory Singapore). A 31-km crater recently discovered under Hiawatha Glacier in Greenland is larger, he adds, but its age is still unclear.

Evidence of an Ancient Impact

In a study appearing December 30th in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Sieh and colleagues laid out four lines of evidence pointing to the existence of a crater under the Bolaven Plateau as the source of the Australasian strewnfield.

Jason Scott Herrin

The researchers first tested the tektite fragments themselves, to see if they contained any basalt, which would indicate their origin on the volcanic plateau. Then they tested the proposed impact site, dating the basalts there and mapping the region's density to look for evidence of a buried impact crater. Indeed, mapping of gravitational anomalies in the area showed hints of a 17-by-13-km crater buried beneath the volcanic plain in southeastern Laos.

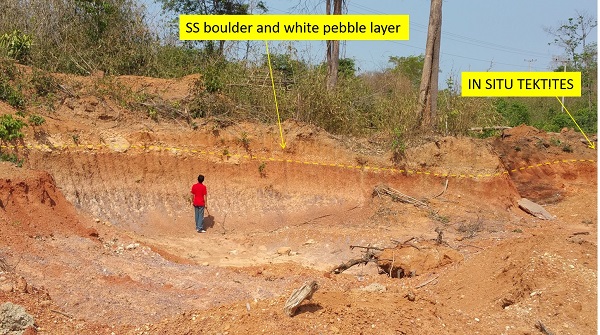

Finally, the team identified small tract of oddly rilled terrain located 10 to 20 km southeast of the volcanic plateau's summit. This is one of the few surface exposures not covered with lava flows, and there the researchers found what appears to be a thick layer of ejecta from the impact.

"Now that we know the site of the impact, we can begin to investigate how the surrounding areas were affected by the impact,” says Sieh. “For example, how thick and coarse was the ejecta blanket 10, 50, 300 kilometers away?” From this, he says, we can understand the effect of the shock wave that blasted outward after the impact.

Intriguingly, the sedimentary layer where geologists find Australasian tektites, which is 790,000 years old, overlaps with the time frame of the sediments in which the 770,000-year-old Peking Man (Homo erectus) was found. Maybe early hominids witnessed this catastrophic event!

Jason Scott Herrin

Even though geologists have known about the Australasian strewnfield for more than a century, the exact location of its source crater has eluded detection until now. Makes you think: What other secrets does the Earth hide just below its surface?

8

8

Comments

Alan-Harris

January 17, 2020 at 4:19 pm

In first paragraph, about size of a 2-km impactor, it would be 100 times larger in diameter than the Celyabinsk impactor, but one million times larger in terms of mass (energy). Relative to the Chicxulub extinction event, it would be around 5-6 times smaller in diameter, or 150 times less massive (energy). The numbers given, without units, seem inconsistent with each other.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

David DickinsonPost Author

January 17, 2020 at 6:08 pm

Thanks... I went with estimated diameter differences for brevity, but yes, the amount of impact energy would be exponential.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Yaron Sheffer

January 21, 2020 at 12:19 pm

Nope... the numbers in David Dickinson's article are OK. Alan-Harris got the asteroid diameter mixed up with the crater diameter. The Chicxulub beast was appx. 30 times larger than 2 km diameter, not merely 5 or 6. Therefore, the former was 27,000 times as massive and energetic as the Asian impactor, NOT merely 150 times...

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Yaron Sheffer

January 21, 2020 at 1:31 pm

Oops oops oops. I was relying on Wikipedia for information, and it turned out to be disinformative. It is well accepted that the KT impactor was about 10 km wide, thus about 5 times as wide as the Asian impactor, confirming Alan-Harris' comment. Wikipedia lists a diameter as wide as 80 km (!), but this is simply lifted from an unpublished paper, and therefore should not have been listed. Ouch.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

David DickinsonPost Author

January 21, 2020 at 6:35 pm

Hi Yaron,

10-km diameter is on the low end of the estimated diameter for the Chicxulub impactor, yes. The best estimates I've come across are 10-80 km from 2014: https://arxiv.org/abs/1403.6391 - is there a source that cites a better estimate?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Giacomo Milazzo

January 20, 2020 at 10:49 am

Hi,

once again I've to remark that the "meteorite meme" is very hard to undermine and most of comment about that event, the K/T mass extinction 65 My ago, refer to that fall.

Has been instead widely proved that the main cause of that dramatic environmental change, has been determined by 30.000 years of basaltic lava flows that interested the Deccan Traps region (today in India).

Not even Alvarez jr believes in the history of the meteorite anymore. It's certainly fell but at most it may have been a destructive event localized in time and space.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Giacomo Milazzo

January 20, 2020 at 10:50 am

I was referring to your phrase: "While the impactor was 30 times smaller than the one that caused the Chicxulub extinction event 65 million yeas ago"

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Yaron Sheffer

January 21, 2020 at 12:33 pm

Just to keep asteroidal impacts in play, I would like to propose that yet another and much bigger asteroid impacted India, and was the initiator of the Deccan basaltic flows

This "who done it" topic was just in the news the other day. Here is the new paper (spoiler: they prefer asteroidal extinction over volcanism):

https://doi.org/10.1126%2Fscience.aay5055

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.