A spectacular fireball seen by hundreds of people from Iowa to Ontario delivered precious samples from the asteroid belt to the lake country of southern Michigan Tuesday night.

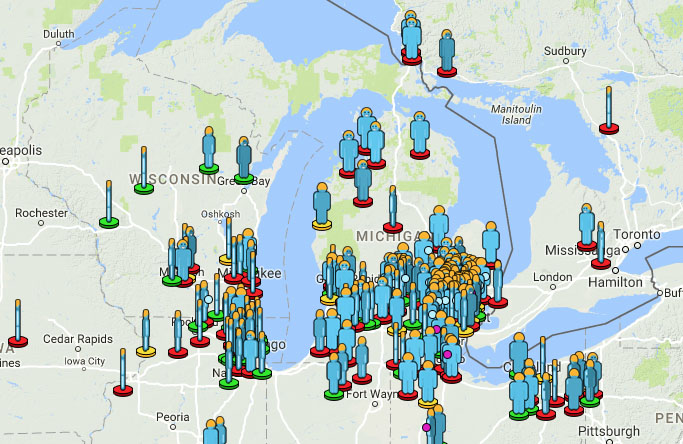

Mike Hankey / American Meteor Society

On January 16th around 8:10 p.m. EST, a brilliant, green fireball crackled across southern Michigan skies. Eyewitnesses described it as brighter than the full Moon with sparks and an orange tail. At least 77 observers reported hearing explosive sounds as the meteoroid broke apart overhead.

The American Meteor Society (AMS), a clearinghouse for meteor sightings, has received 657 reports of the fireball with some as far away as Iowa and southern Ontario.

The fireball traveled relatively slowly at around 45,000 km (28,000 miles) per hour. That sounds fast, but it's more than 4½ times slower than a typical summertime Perseid. Its slow speed and great brilliance suggests a fairly large space rock that penetrated deep into the atmosphere, according to Mike Hankey of the AMS.

American Meteor Society (AMS)

While fireballs are relatively common, ones that drop meteorites are rare, and it's rarer still for someone to find those black treasures. But by using Doppler weather radar data and seismic traces (more on that in a moment), meteorite hunters were able to pinpoint the strewn field, the name for the ground footprint where the space rocks might have fallen. Lately of the asteroid belt, these interplanetary fragments now call the Township of Hamburg, Michigan, home.

Google / AMS

The strewn field extends about 5 miles, oriented east-southeast to west-northwest, from about Highway 23 up to Bass Lake, some 20 miles northwest of Ann Arbor. Since the area has many lakes, make sure the ice is sound before venturing out.

Anyone living in that area should be on the lookout for black rocks poking out of the snow similar to what Ward is holding in the photograph above. The black coating, called fusion crust, forms when the outside of the meteoroid is heated and melted by friction from the air during its flight through the atmosphere. Fusion crust is typically only 1-2 mm thick.

Rob Matson

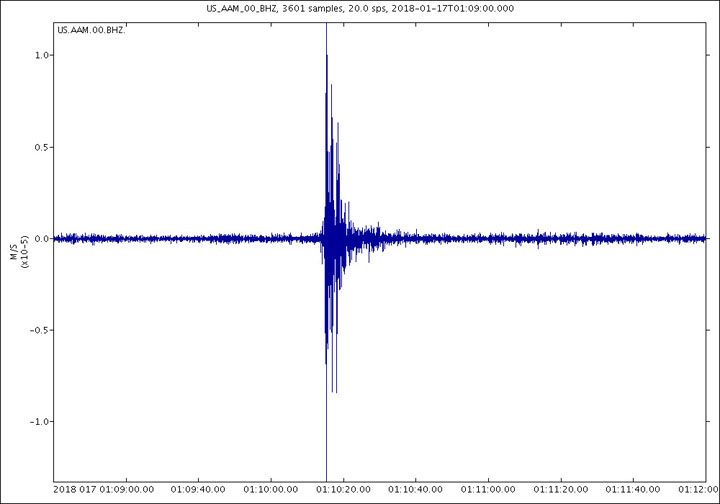

The Michigan fireball not only put on a light show, it "knocked down the door," announcing its arrival with a 2.0-magnitude seismic event recorded by the U.S. Geological Survey. The blast was not from the impact itself but from the air pressure wave created during the explosive breakup of the meteoroid in the atmosphere.

A preliminary analysis indicates it's possibly an L6 chondrite, a common stony meteorite type. The "L" stands for low iron and "6" (on a scale from 3 to 7, from least to most altered by heat) indicates that the meteorite was strongly heated, so it likely originated from a larger asteroid. Samples are on their way now to the Chicago Field Museum for more detailed analysis.

12

12

Comments

Anthony Barreiro

January 19, 2018 at 3:32 pm

Peter Jenniskens of SETI and NASA Ames once gave a talk to my astronomy club about meteorite hunting. He advised against using a magnet to search for meteorites. An iron-bearing meteorite will be attracted to the magnet, but the magnet will scramble whatever weak magnetic signature the meteorite may have brought to Earth, destroying information that would be useful to researchers. Jenniskens also said not to pick up a meteorite with your bare hands, as the oils in your skin will get into the meteorite and, again, degrade the usefulness of the meteorite to researchers. He said aluminum foil is good to use to handle and store meteorites. So I'm surprised to see a self-described professional meteor hunter holding a fresh meteorite with his bare thumb and forefinger.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

January 19, 2018 at 6:05 pm

Hi Anthony,

True enough. My guess and only a guess is that an untouched piece was shipped out for study and classification, and that he'll probably keep this one. Robert's a savvy guy and he works with museums and classifiers, so I'd assume he the right thing.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Anthony Barreiro

January 22, 2018 at 2:24 pm

Thanks Bob. I guess that's a fair guess!

Hopefully some of these meteorites have been handled carefully for study by planetary scientists.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

January 22, 2018 at 2:28 pm

Anthony,

Still just a guess, but at least we know for certain that the Michigan planetarium director has untouched material as reported in today's story.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Anthony Barreiro

January 22, 2018 at 7:17 pm

Yes, I saw your report. It's great that so many meteorites are being recovered! All that snow and ice is good for something!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Mandusky

January 19, 2018 at 6:42 pm

I may have an ignorant question but I don’t know who else to ask so here we go:

I live in Cleveland, OH, and shortly before news reports of the fireball began to surface, I noticed what appeared to be a flair falling straight down from the sky. I found it odd considering it was at night and was falling in a rather unpopulated area, so was confused as to its’ origins. Fast forward a couple of hours and reports of the fireball started leading me to believe what I saw was possibly a remnant from the same event observed over Michigan.

I have not been able to go look around the area in the daylight as of yet, but my question is could it be possible for a fragment to have fallen, in tact, as far away as Cleveland? Or would I just be wasting my time?

Any info or feedback would be appreciated!

Thanks!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

January 19, 2018 at 7:15 pm

Hi Mandusky,

What time did you see the flare?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Tslisher

January 19, 2018 at 11:40 pm

Bob,

I led a team from Longway Planetarium that have recovered 3 pieces so far. Please contact me we would like to get this story out. [email protected].

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

January 20, 2018 at 1:05 am

Hi Todd,

Will do. I see your team did very well. Nice, fresh specimens.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Graham-Wolf

January 23, 2018 at 9:31 pm

Great work!

These little critters can be rather hard to find.

The icy snows provided a useful contrast to locate them.

Trusting the samples were properly handled and not bio-contaminated...

Congrats to the metorite recovery team.

They certainly pulled it off.

And so soon after the event!

We don't get so lucky down here.

The last big one in NZ that I'm aware of... was the Waingaromia "Iron" Meteorite ( later cut and etched to show Kamacite lamellae) many decades ago... ~ 1930 I understand. I've actually handled it ~ 1990 at a NZ Stardate Conference near New Plymouth. It weighs several Kg. Bigger than clenched fist size!

Graham W. Wolf at 46 South, Dunedin, NZ.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

milly

January 27, 2018 at 7:14 pm

Another ignorant question. why does the score of six--indicating it was strongly heated--prove it came from a large asteroid? And when did that happen?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

January 27, 2018 at 7:52 pm

Hi Milly,

Great question! Meteorites are classified in a couple of different ways, one according to composition / iron content and a second, according to petrological type. The Michigan fall is likely an L-chondrite, with L indicating a low iron amount. H-chondrites have a higher iron content. LL-chondrites have an even lower iron content. Further, chondrites of the L-type can range from pristine, meaning little altered by heat and pressure (L3), to highly altered by these processes (L6 or L7). A key sign of alteration is the disappearance of those distinct little pellets or grains in meteorites called chondrules. Under heat and pressure -- likely from being buried inside an asteroid large enough to create those pressures and with a significant amount of radioactive elements to produce heat -- chondrules recrystallize into a homogenous mass. Asteroid material can also be heated and metamorphosed by impact, too. So it's possible an impact may also have been involved in the Michigan meteorite's formation.

Above all keep in mind that the meteorite has yet to be classified, so it may turn out to be different type in the end. Another well-known meteorite hunter thinks it might be an H4 or H5. We'll know soon enough!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.