This view of totality, taken on January 9, 2001, by Swedish astrophotographer Bengt Ask, shows the eclipsed Moon amid several bright stars in Gemini. He used an 8-inch Schmidt-Cassegrain reflector with a focal reducer and a 6-second exposure on ISO 400 film to capture this scene. Totality on October 27–28, 2004, may look like this, as the geometries of the 2001 and 2004 eclipses are similar.

Courtesy

The best astronomical events usually seem to happen at the worst times and places — at 3 a.m. low above your most obstructed horizon, or maybe only in East Antarctica. But not this time, not for observers anywhere in the Americas. On October 27, 2004, the full Moon will undergo a deep total eclipse lasting for 1 hour 22 minutes, when it will be high in the eastern sky after dark but while most people are still awake and about.

The only slightly problematic area will be near the West Coast of North America, where the partial phase of the eclipse will begin just a few minutes after sunset and moonrise. But if you have an open view low to the east, even this situation will only add to the drama. As twilight fades, westerners will see the shadow-bitten Moon coming into stark view low above the landscape, and by the time totality begins, the sky will be getting quite dark and the Moon will be fairly high.

What's more, in a conjunction of events never before seen in history, this eclipse happens during Game 4 of the World Series. The World Series Lunar Eclipse should be visible to fans with good sight lines from Busch Memorial Stadium in St. Louis, and we can hope that TV crews periodically aim up to show the progress of the event — if the sky is not too cloudy! Millions of watchers could be inspired to duck outside for a look between innings. (P.S.: Go Sox!)

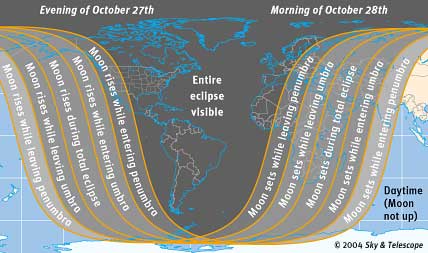

Europe and much of Africa also get a good view of the eclipse, but at a less convenient time: before dawn on the morning of October 28th.

Find your location to see whether the Moon will rise or set during any phase of the eclipse for you. Because an eclipsed Moon is always full, the Sun sets or rises almost simultaneously — on the opposite horizon.

Sky & Telescope: Gregg Dinderman.

If you're clouded out (or can't see the eclipse from your location), try these sites for possible live webcasts of the eclipse:

- MIRA Public Observatory, Belgium

- Saro Group Scientific Expeditions, Canary Islands

- Universidad de Sonora, Mexico

- ParsSky.net, Iran

- AstroNet, Netherlands

- East Antrim Astronomical Society, Northern Ireland

- Friends of Astronomy, Argentina

- SLOOH Observatory, Canary Islands

The Sequence of Events

During this eclipse, the Moon (in Aries) crosses deep inside the northern part of Earth’s shadow core (the umbra). The partial phases before and after totality occur while the Moon is moving across the umbra’s edge. Much less noticeable are the stages when the Moon is in the shadow’s pale penumbra. The diagram gives Universal Times on October 28th. The table at the bottom of the page lists the corresponding Eastern, Central, Mountain, and Pacific Daylight Times on the evening of the 27th and morning of the 28th.

Sky & Telescope: Gregg Dinderman.

The illustration at right shows the Universal Times of events as the Moon moves into and out of the two parts of Earth’s shadow: the penumbra, the shadow’s pale outer fringe, and the umbra, the darker central region. The table below gives the civil times of events in North American time zones.

The outermost part of the penumbra is so lightly shaded that you won’t notice any change on the Moon here at all. But by the time the Moon’s leading edge gets about halfway across the penumbra, you may begin to detect a very weak dimming of the Moon’s eastern side. How early can you be certain you see it? As the Moon advances farther across the penumbra, the shading becomes much stronger and more obvious.

When the Moon’s edge first reaches the umbra, true partial eclipse begins. The change is dramatic. A dark dent forms in the Moon’s eastern side, and as the minutes tick by, the dent becomes a big, curved bite. In a telescope you can watch the umbra’s slightly ill-defined edge engulf one familiar lunar feature after another.

After 1 hour 9 minutes of partial eclipse, the last edge of the Moon slips out of partial sunlight into the umbra. But already it has become apparent that the umbra is not completely dark. The shaded area of the Moon glows with a weird reddish hue — anywhere from bright sunset-orange to dark blood-black. This illumination on the Moon is sunlight that is bent by our atmosphere around the edge of Earth into the planet’s shadow. The strange light on a totally eclipsed Moon is the combined illumination from all the sunrises and sunsets ringing the Earth at the time.

The actual brightness of the Earth’s sunrise-sunset ring depends on weather conditions around the world and especially on the amount of dust suspended in the upper atmosphere. A clear stratosphere on Earth generally produces a bright and colorful lunar eclipse, with coppery and orange colors predominating. A major volcanic eruption can load the stratosphere with a thin haze of ash and dust, resulting in very dark lunar eclipses — such as occurred for several years after the enormous eruptions of Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines in 1991, Mexico’s El Chichón in 1982, and Indonesia’s Mount Agung in 1963. Recent lunar eclipses have been much lighter, and this one should be too.

Even during a given eclipse, colors and shades in the umbra can be surprisingly varied. The Moon will pass north of the shadow’s center this time, so around mideclipse time the north (upper) part of the Moon will almost certainly look brighter than its bottom part — because that region will be closest to the umbra’s edge. Time-lapse photography sometimes reveals mysterious bands of darker shadow sweeping across the Moon during totality. Around the beginning and end of total eclipse, you’ll probably see a bright yellowish or even bluish white arc just inside the umbra’s edge. These effects can give the eclipsed Moon a remarkably three-dimensional appearance, making it look like a luminous rotten orange.

After totality, the partial phases unwind in reverse order as the Moon creeps out of the umbra. But even when the last edge of the Moon leaves the umbra, the show is not over. The penumbral shading should remain visible on the Moon’s celestial west (right) side for another 30 minutes or so. When will you lose the last definite trace of it?

Total Eclipse of the Moon, October 27–28, 2004 Eclipse stage UT Eastern Daylight Time Central Daylight Time Mountain Daylight Time Pacific Daylight Time Moon enters penumbra 0:05 8:05 p.m. 7:05 p.m. 6:05 p.m. -- First visible shading? 0:45 8:45 p.m. 7:45 p.m. 6:45 p.m. -- Partial eclipse begins 1:14 9:14 p.m. 8:14 p.m. 7:14 p.m. -- Total eclipse begins 2:23 10:23 p.m. 9:23 p.m. 8:23 p.m. 7:23 p.m. Total eclipse ends 3:45 11:45 p.m. 10:45 p.m. 9:45 p.m. 8:45 p.m. Partial eclipse ends 4:54 12:54 a.m. 11:54 p.m. 10:54 p.m. 9:54 p.m. Last visible shading? 5:25 1:25 a.m. 12:25 a.m. 11:25 p.m. 10:25 p.m. Moon leaves penumbra 6:03 2:03 a.m. 1:03 a.m. 12:03 a.m. 11:03 p.m.

Estimating Brightness

Aligning his camera on the same star for nine successive exposures, Sky & Telescope contributing photographer Akira Fujii captured this record of the Moon's progress dead center through the Earth's shadow during the July 2000 total lunar eclipse.

About a century ago, the French astronomer André Danjon devised a scale for rating the overall darkness of lunar eclipses. Estimates of the “Danjon number” form another long-running record of lunar-eclipse variations, so they are well worth continuing — again, partly to calibrate what the number may say about atmospheric conditions before modern types of measurements. Here are Danjon’s L (for luminosity) values:

Danjon Scale of Brightness L Value Description 0 Very dark eclipse, Moon almost invisible,

especially at midtotality.1 Dark eclipse, gray or brownish coloration;

details distinguishable only with difficulty.2 Deep red or rust-colored eclipse, with a

very dark central part in the umbra and

the outer rim of the umbra relatively bright.3 Brick-red eclipse, usually with a bright

or yellow rim to the umbra.4 Very bright copper-red or orange eclipse,

with a bluish, very bright umbral rim.A fractional estimate, such as 1.8 or 3.2, may seem most appropriate.

A more objective method is to estimate the actual stellar magnitude of the eclipsed Moon, using the “reversed binocular” trick. This was recently perfected by Brazilian observers Helio C. Vital, Alexandre Amorim, Willian Souza, and Antonio R. Campos. During the total lunar eclipse of May 15–16, 2003, for instance, they found that the Moon seen through one barrel of backward-turned binoculars matched the brightness of the star Pi Scorpii (magnitude +2.9) seen in the open sky. Prior tests had established that the binoculars produced 5.0 magnitudes of dimming. This meant that the eclipsed Moon was magnitude –2.1.

Please e-mail any of these observations you make to [email protected] giving your full name and address, the telescope aperture and magnification, and the sky conditions.

Eclipse Photography

This interesting chronicle of totality on November 8, 2003, was made by Joe Pedit from Cusco Willa, Virginia. He used a stationary Nikon N90s SLR camera with a 24-mm lens at f/22 and Kodak Professional Supra 400 color-negative film for this exposure lasting 3 hours 21 minutes. The intense brightness of the full Moon overexposed the beginning and end of the trail.

Unlike a total eclipse of the Sun, which usually lasts for only a few frenzied minutes, a total lunar eclipse happens at a much more leisurely pace. For example, on October 27th the Moon will be completely immersed in Earth’s shadow core, or umbra, for 1 hour 22 minutes. This makes it a treat both to watch and to image, using either still or time-lapse photography — especially if you have a long lens or can shoot through a telescope. See either "How to Capture October's Lunar Eclipse" in the October 2004 issue of Sky & Telescope magazine, or the online article "Observing and Photographing Lunar Eclipses" for guidelines on shooting a lunar eclipse.

Just hope for clear weather! The world has had a run of four total lunar eclipses (counting this one) in just the last year and a half, but there won’t be another one visible from anywhere until March 3rd and August 28th of 2007. Europe and the East Coast of North America are favored for the first of these, western North America for the second.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.