November 16: ISON's outburst holds on. Magnitude estimates from this morning (roughly Nov. 16.5 UT) are running about 5.5. The shape of the head seems to be changing, as if the bright globe of the last few days is thinning and being pushed tailward into a parabolic shape. At least that's what I see comparing the first two pix here, taken on November 16th and 14th by Jean-François Soulier and Alain Maury.

November 15: ISON's awakening continues. This morning observers are estimating it at 5th magnitude. Visually it's a popsicle: with a round, sharp-edged, bright green head and a long, narrow, dim tail.

In deeper images, such as this fantastic shot by Damian Peach, the tail is becoming wider and full of detail. (Peach used a 17-inch PlaneWave CDK reflector for 12 minutes of exposures.)

Watch fine structure in the tail in these wide- and narrow-field animations by Joseph Brimacombe.

At high telescopic magnifications, no one is reporting any sign so far that the nucleus is breaking up — good news. If the brightening of the last few days is due to a breakup getting under way, there could be very little of anything visible in December after perihelion. The next few days should tell.

November 14: Comet ISON Comes to Life! Veteran comet observer John Bortle reports that Comet ISON is undergoing a major outburst. By his estimate, it was six times (2 magnitudes) brighter when he observed it this morning than on the previous morning. See article Comet ISON Comes to Life!

Although moonlight returns to the pre-dawn sky on the 16th, here are finder charts for ISON and Lovejoy for the second half of November. Binoculars should see through the moonlight and zodiacal light very well. Observers with very dark, clear skies have started reporting both naked-eye.

November 13: The upstaging by Comet Lovejoy continues. ISON now has a total magnitude of about 7.5. Lovejoy is 6.5 and much higher in the sky. See Tony Flanders' The Other Great Morning Comet.

Here's a November 13th image of Comet Lovejoy, with enhancements (the insets on its right) to bring out the subtle fan and jets near the nucleus; source.

Meanwhile the other two pre-dawn competitors, Comets Encke and C/2012 X1 (LINEAR), are very low and have become hard to see.

November 12: ISON's tail doubles. As ISON speeds sunward — and moves lower now into the dawn — its straight, narrow tail is developing interesting structure: Nov. 7 photo, Nov. 10 photo, Nov. 12 photo.

November 6: A comprehensive look ahead. Three weeks before perihelion, Matthew Knight at NASA's Comet ISON Observing Campaign (CIOC) posts an analysis of What might happen to Comet ISON from here on out? The TL;DR version: a fine naked-eye display in December is still a very real possibility.

November 4: ISON has lots of predawn company! ISON continues to brighten and enlarge more slowly than expected as it falls toward the Sun. It's currently about 8th magnitude (estimates differ), with a very condensed head and — as you'd expect for a comet flying almost straight toward the Sun — a narrow, very straight tail. However, its actual dust production doesn't seem to be increasing, despite the increasing warmth of sunlight.

By a happy coincidence, three other comets for big binoculars and small scopes are also in the eastern sky before dawn, and one of them, Comet Lovejoy (C/2013 R1), is stealing the show! Greg Crinklaw writes,

Northern Hemisphere observers have a rare treat waiting in the morning sky: four [relatively] bright comets viewable in small telescopes and/or binoculars. They will be available every morning through November 14th, after which the Moon will interfere. With all the media hype about comet ISON, many people are not aware of this -- sadly even many of those who have ventured out recently in the morning to view ISON, which is the most difficult of the four to see.

See comets.skyhound.com for complete information and finder charts for all four. Hurry up before moonlight enters the predawn picture after November 14th or 15th.

October 25: Piles of new pix. Damien Peach just posted a lovely image of ISON passing the galaxy M95 in Leo, which gives a good idea of how visible the comet is in a telescope right now compared to a familiar Messier galaxy.

See lots more images on our online photo gallery, as well as SpaceWeather.com's photo gallery.

October 18: Holding steady . . . Comet ISON continues to brighten slowly but steadily. It's now about 10th magnitude, with a condensed head and a narrow, straight tail. It's moderately low in the predawn sky.

This image by Michael Jäger from October 13th is typical of the best current amateur pix. Michael Jäger |

Visually it's not exactly an easy target. S&T's Tony Flanders took a good look with his 12.5-inch reflector. He writes,

The weather in New England was poor in early October, but I finally got a chance to observe Comet ISON at 5 a.m. EST on the 12th. I was using my 12.5-inch Dob in the backyard of my country home, and at altitude 26° ISON had barely emerged from the light dome of nearby Pittsfield, Massachusetts.

The transparency was excellent but the seeing was poor, which may be why I could see neither a tail nor a pseudo-nucleus. Instead, ISON appeared as a faint elliptical blob about 2? × 1?, rather like an elliptical galaxy. It was not especially easy to see nor especially hard; I’m sure I could have spotted it through an 8-inch scope.

Alfons Diepvens in Belgium has been updating his standardized red-light CCD light curve, and it still doesn't look promising for the comet breaking easy naked-eye visibility, since it will be near the Sun when brightest. Here's a more scattered, all-encompassing light curve (scroll down).

Will the comet's nucleus break up around its November 28th perihelion? Three developments regarding this crucial question:

• The comet is more likely than not to survive perihelion intact, conclude Matthew M. Knight and Kevin J. Walsh. The nucleus is probably dense enough to hold together against the Sun's tidal effect, they say, unless it happens to be spinning the right way. That's not particularly good news. Although an intact nucleus would mean something comes out the other side from perihelion into the early December dawn, it wouldn't be the bright dust-fountain that might result from a post-perihelion breakup.

• A Hubble Space Telescope image on October 9th showed every sign that the comet's nucleus was still entirely intact. Photo, press release.

• Zdenek Sekanina concludes after a long analysis that "overall, C/2012 S1 is looking reasonably healthy but not exuberant."

Comet ISON (top) in its conjunction with Mars and Regulus on the morning of October 14th. Imager Chris Schur in Arizona used an 80mm f/4.8 apo refractor for 10 minutes total exposure. The field is about 2½° tall. North is up. |

September 25: A new projection. Alfons Diepvens in Belgium has long been taking consistent images of the comet in red light, which tracks its dust production (i.e. reflected sunlight). A comet's dust production rate is crucial to a bright tail. An analysis by Eric Broens of this data (using the total coma brightness) and a projection forward suggest that the comet will never crack naked-eye visibility. See graph and details.

New wide-field color image by Michael Jäger September 28th.

ISON, Mars, and asteroid 433 Eros in one 2.6-°-wide frame, by Rolando Ligustri September 28th.

This assumes that the comet's nucleus will stay intact. Hope for anything much brighter depends the nucleus undergoing a major breakup at or just after perihelion November 28th — which is quite possible and maybe even likely.

September 17: Brightening... gradually. The image below, taken this morning by Alfons Diepvens in Belgium, is typical of the best pictures now coming in from amateurs around the world.

Comet ISON at 13th magnitude on September 17, 2013. Alfons Diepvens used an 8-inch apo refractor with a CCD camera for 55 minutes of exposures tracking the comet.

Alfons Diepvens

The comet is still about 12th or 13th magnitude. Diepvens' exposures tracked it as it moved, turning stars into streaks. The comet is heading almost straight toward the Sun, which is why its tail is nearly aligned with its motion. This situation will continue until late November.

As for how bright the comet will become, there's really no saying. Everything depends on whether and when the comet's nucleus will break up near perihelion November 28th. Too early a breakup would extinguish the comet completely. A breakup right after perihelion could produce a long-tailed spectacle in the December dawn, mimicking Comet Lovejoy of 2011. That comet, a Sun-grazer like ISON, was still 13th magnitude just three weeks before its perihelion breakup.

August 26: Yep, it's faint. In the last two weeks more than a dozen additional brightness observations have been reported for the comet, low in the dawn. They average magnitude 14.0, confirming Bruce Gary's recovery observation. Not looking good — but comets can be unpredictable.

August 13: Spotted again at last! But sadly faint. A couple weeks earlier than we expected, skilled amateur imager Bruce Gary in Arizona has apparently become the first person to pick up Comet ISON after its 2½-month intermission behind the glare of the Sun. He succeeded in recording a fuzzy point with an anti-sunward tail at Comet ISON's exact predicted position among the stars. Measuring the image, Gary comes up with a V magnitude of 14.3 ± 0.2.

This puts a damper on Comet ISON's prospects. See our article Comet ISON Spotted Again, Faintly.

August 9: Science from space begins. Although comet ISON is still less than 18° from the Sun as seen from Earth and hidden in the solar glare (being still faint), that's not stopping spacecraft elsewhere in the solar system.

The old Deep Impact/ EPOXI probe scheduled observations for August 8th and 9th [but the spacecraft has since apparently failed].

• Then follow observations from the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter on August 20th. Lots of details are available at Part 2 of the Comet ISON Observer's Workshop — watch from 24:55 to 27:50, 34:45 to 35:30, and 41:13 to 41:23.

While we're at it, here are links to all observing plans by professional astronomers known to NASA's Comet ISON Observing Campaign. See also the campaign's blog.

Also, Hubble's ISON blog.

Amateurs are already trying to recover ISON, which should be 13th

magnitude by now, though we've had no reports of success. We're expecting it to be recovered from Earth around the end of August.

June 2: Latest assessment. Comet ISON was still stuck at about 16th magnitude as of May, when it was becoming difficult to observe. John Bortle has posted an updated assessment, which should stand unchanged until the comet comes out from the glare of the Sun in late August.

Read Bortle's assessment here.

Comet ISON as imaged by Hubble on April 10, 2013. More / larger pix.

NASA / ESA / J.-Y. Li (Planetary Science Institute) / Hubble Comet ISON Imaging Science Team

April 23: Hubble photo and another size estimate. NASA released the Hubble Space Telescope photo at right, taken April 10th when the comet was still 4.15 a.u. from the Sun. The researchers involved write the following:

"Preliminary measurements from the Hubble images suggest that the nucleus of ISON is no larger than 3 or 4 miles (5 to 6.5 km) across. This is remarkably small considering the high level of activity observed in the comet so far, said researchers. Astronomers are using these images to measure the activity level of this comet and constrain the size of the nucleus, in order to predict the comet's activity when it skims 700,000 miles above the Sun's roiling surface on November 28."

Press release with links to larger images.

New Hubble pix from April 30th.

April 8: Good news from Swift. NASA's Swift spacecraft measured the comet in ultraviolet on January 30th and in February, and found that its nucleus was spraying 850 tons of dust per second even when still 2.7 a.u. from the Sun. Program scientists estimate that this means the comet's nucleus is roughly 5 km wide. That's about 10 times larger than another Sun-grazer, Comet Lovejoy (C/2011 W3) in 2011, which became a long-tailed spectacle. However, ISON's water-vapor production was very low; carbon dioxide and/or carbon monoxide vaporization still seems to be the driving force, and no one knows how long these more volatile substances will last.

NASA press release.

Here's a 35-minute video of the comet barely creeping across the stars on April 7th, still at magnitude 16.1, made by two observers at the University of Narino in Colombia (courtesy SpaceWeather.com).

March 19: Back to some pessimism. Clay Sherrod reports, "Unfortunately we are seeing a dip in total brightness and size of the comet; we have logged it dropping from a maximum magnitude of 15.7 two weeks ago to this morning's measurement of 16.1 and 16.2. The size has likewise diminished.... The overall intensity and size are decreasing at this time."

February, March, and April are predicted to be a time when ISON is brightening only a little, but not actually dimming.

Feb. 28: And now on the optimistic side.... After my February 21st post below gave David Seargent's pessimistic view, Daniel Fischer calls attention to an analysis by Ignacio Ferrín, comet expert in Colombia, who finds a 75% chance that ISON has already undergone its brightening slowdown, meaning it should be on track for that magnitude minus-12 perihelion peak after all. Ferrín writes,

"The reason for this is that the current power law describing the brightness is rather steep, increasing at a rate R^4.35....

"We have calculated the temperature of the object at perihelion and find T = 2900º K, sufficient to melt lead and iron.

"Additionally the comet will penetrate the forbidden region defined as Roche's Limit. Any object within Roche's limit has a large probability of disintegrating due to differential gravitational forces from the Sun. The combinations of Roche's Limit, plus solar radiation plus very high temperature, suggest that the comet may not survive its encounter with the Sun, disintegrating into several pieces. Or it may survive, if its internal cohesion is sufficient to endure those conditions."

References:

http://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv/papers/1302/1302.4621.pdf

http://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv/papers/0909/0909.3498.pdf

On the other hand, Ferrin's way of interpreting visual brightness estimates is being criticized.

Feb. 21: Again, a "great comet" to weaken? From Australia, longtime comet expert David Seargent posts to the comets-ml mailing list:

"All recent upgrades of the orbit of this comet give weakly hyperbolic eccentricities, suggesting that it is coming in from Oort Cloud distances and is probably making its first (and only?) close approach of the Sun." That's a formula for early false promise followed by a slowdown of brightening. Right now, says Seargent, "there must be something more volatile than water ice at the surface of the nucleus, which seems unlikely if the comet had experienced previous episodes of fierce heating at sunskirting distances."

Accordingly, says Seargent, ISON's future brightness development will probably be like that of Comet PanSTARRS (C/2011 L4): fairly steep brightening until it's within about 1.7 astronomical units from the Sun — meaning late September 2013 — "followed by a very slow increase until perihelion," its closest approach to the Sun on November 28th.

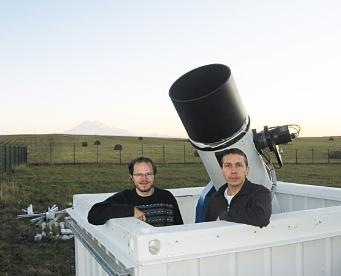

Comet ISON discoverers Artyom Novichonok (left) and Vitaliy Nevskiy with the 16-inch Santel reflector used in their discovery in Russia. ISON is named for the International Scientific Optical Network, of which they are a part.

Vitali Nevski

Fitting this model to recent observations "has the comet barely brighter than magnitude 5 in mid-November, about –4 or –5 near perihelion [when it's just a couple degrees from the Sun in the daytime sky], and magnitude +1 or better in early December. Northern observers should see a moderately bright comet, most probably sporting a very long and intense tail. For us in [the Southern Hemisphere], however, it seems as though it will be marginally naked-eye at best."

Also, its much-speculated connection to the Great Comet of 1680 now seems ruled out.

P.S. from Alan MacRobert: As an example of the stuff that's causing friends and relatives to ask me about the "monster comet coming," this appeared on the popular science site Red Orbit:

". . . Viewers can expect to see a rapid whirling of the comet as it engages in a near hairpin-like turn around the Sun . . . The comet will become dazzlingly bright, rivaling the brightness of a full moon, as it streaks across our sky."

See the ridiculous graphic for yourself.

Read our Comet ISON preview in the January 2013 issue of Sky & Telescope: A Great Comet Coming? by John Bortle.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.