About a decade ago, mid-November's normally benign Leonid meteor shower exploded like fireworks into prominence, giving us dazzling displays of shooting stars almost too numerous to count.

During the four evenings of November 16–19, 2008, Chris Peterson recorded 141 meteors during the Leonid meteor shower. "Because the images were collected over many hours," he notes, "the radiant of the shower is spread out." Click here to see the entire image at larger scale.

Chris Peterson / Cloudbait Observatory

I remember these celestial spectacles as if they were yesterday. In 1999, I was flying in a research jet in the darkness over Sicily with a team of NASA scientists and veteran amateur meteor counters. Out of the plane's window I could see meteors raining down from space, a deluge so intense it appeared as if Earth were under attack.

A year later I sat with my wife and some friends overlooking a smooth-as-glass lake in western Massachusetts. In the predawn quiet we savored the sight of Leonids streaking into view all across the sky, sometimes arriving two and three at a time.

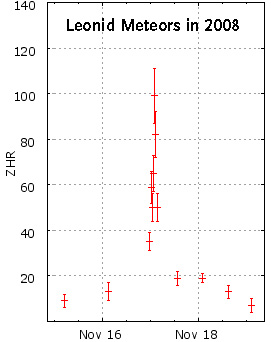

Combined observations from observers in Europe, Asia, and the U.S. clearly show the sharp spike in meteor activity during the 2008 Leonid shower.

International Meteor Organization

If new predictions by meteor specialists hold true, we could be in for a repeat of this celestial treat in 2009. That's because last November, despite strong interference from moonlight, observers in Europe, Asia, and the U.S. counted upward of 100 meteors per hour, as plotted at right. Yet the expectation was closer to 10 — so why the outburst?

The Leonids are bits of debris spread along the orbit of a periodic comet named Tempel-Tuttle, which has a 33-year-long orbit that can bring it rather close to Earth. (In 1366, for example, it passed only 2 million miles from us, one of the very closest passes that any comet has made in recorded history.)

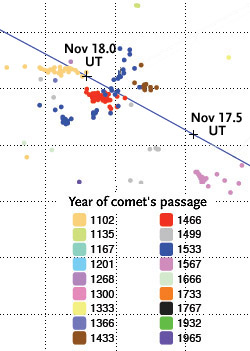

Each time it rounds the Sun, Tempel-Tuttle spews out a ribbon of dust that remains fairly concentrated for centuries as it follows the comet around in orbit. During the 2008 pass, Earth came rather close to the debris ejected in 1466, about 16 orbits ago. Although aware of this stream's proximity, few meteor specialists expected much from it. (One who did was Russian dynamicist Mikhail Maslov.)

With the sudden realization that this 542-year-old ribbon of rubble still packs a punch, everyone's gone back to the drawing board to recalculate next year's circumstances. The main peak of activity will come on November 17th and involve contributions from the comet's spewings in 1102, 1466, and 1533. On that much, at least, three teams' calculations agree. But otherwise their results, like the meteors themselves, are scattered:

In November 2009, Earth (blue line) will pass through multiple trails of dust ejected long ago by Comet Tempel-Tuttle, particularly those from 1466 and 1533. For the full plot, click here.

William Cooke / NASA-MSFC

• Maslov predicts a brief outburst of 170 to 180 meteors per hour centered at 21:35 UT, with smaller secondary peaks (20 to 25 per hour) on November 16th at 13:30 UT and again on the 18th at 19:24 UT.

• Jérémie Vaubaillon (Caltech) initially predicted a maximum of nearly 500 Leonids per hour at 21:43 Universal Time. He has since scaled back his expectations and now predicts a maximum closer to 200 per hour, with the peak perhaps delayed by 30 minutes to 1 hour.

• William Cooke (NASA Marshall Space Flight Center) is more optimistic, saying that the shower will top out at nearly 300 — give or take 100 — at 21:44 UT.

Fortunately, the Moon will be just past new on the 17th, so skies should be good and dark. Unfortunately for those of us in the Americas, this outburst will be rather short (lasting an hour or so) and occur at or before sunset. Observers in Asia will have the front-row seats — though conceivably, Cooke notes, there might be a nice show over North America when darkness falls hours after the peak.

2

2

Comments

BDan

November 7, 2009 at 11:52 pm

The timing is rather more unfortunate for the Americas than you say: due to the orbital geometry involved, the Leonids are only visible in a given location after about local midnight, so simply waiting for darkness will not help much. That means that in EST, no Leonids will be visible until about seven hours after the predicted peak, and ten hours for PST. This is not reason to despair, though: during the previous string of good Leonid years, there were several good shows at times significantly different than had been predicted.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

pk

November 16, 2009 at 1:17 pm

The suggestion that 'there might be a nice show when darkness falls hours after the peak' is misleading. The big problem is not waiting for darkness, but waiting for Leo to rise. If the radiant is not up in the sky but is below the horizon, then a meteor coming from that radiant would have to pass through the earth to get to you!

For us east-coast-ers, Leo will not rise until after midnight. 🙁

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.