Back in 2006, astronomers used the Hubble Space Telescope to watch vast numbers of stars in the Milky Way's central bulge to look for gravitational lensing by extrasolar planets. The observations revealed 16 Jupiter-sized planetary candidates and also, as a byproduct, identified 42 oddly bright blue stars within the bulge. Astronomers think that many or most of these are “blue stragglers”: old stars that, for reasons uncertain, burn as hot and bright as if they were part of a young stellar population. Bulge stars are supposed to be very old.

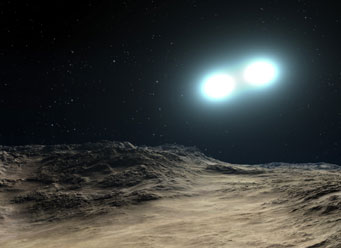

An artist illustrates the formation of a blue straggler by the merger of a close binary pair. When the two stars merge, the newly massive single star begins to fuse its hydrogen more intensely, almost as if it were truly newborn.

NASA, ESA, and G. Bacon (STScI)

Blue stragglers have intrigued astronomers since 1953, when Allan Sandage discovered them among the ancient stars of the globular cluster M3. Stars that form at the same time, such as in a cluster, should evolve together. But blue stragglers look rejuvenated — long after their equally massive peers have evolved into red giants or on to white-dwarfhood. In the standard explanation, a blue straggler has acquired a great deal of fresh mass from another star, perhaps by a collision and merger, and as a result is now fusing hydrogen at the fast pace of a younger star.

The star merger could be the result of a direct collision or, perhaps more likely, the result of a close miss that results in a close binary that eventually spirals together. Only where stars are stars are much closer together than in our own vicinity is this ever likely to happen.

The galaxy's central bulge is indeed dense toward its center, as are globular clusters. And in a population of old stars, such young-looking ones stand out. At a press briefing earlier this month at the American Astronomical Society’s Boston meeting, Will Clarkson, the Indiana University investigator who led the study, said that only 3.4% of the galactic bulge’s stars formed in the last five billion years.

While these reborn stars are commonly seen in globular clusters, this is the first time they’ve been spotted within the bulge itself. “Every new environment we can find these blue stragglers in is good,” said Clarkson. He and other experts believe that these oddballs have much to reveal about the formation and evolution of stars generally.

The Hubble Space Telescope had to peer through some 20,000 light-years of foreground stars to examine stars of the Milky Way’s dense central bulge. The observations revealed a scattering of odd stars known as "blue stragglers," once similar-looking foreground stars were eliminated by their motions.

NASA, ESA, W. Clarkson (Indiana University and UCLA), and K. Sahu (STScI)

But Clarkson noted that isolating them in the galactic bulge was tricky. Hubble peered at this distant region through a haze of foreground stars of all ages. The team had to filter these out to get a clean sample of bulge stars. They used the different speeds at which these two star populations orbit the galactic center to make this distinction.

“Stars that are closer [to us] seem to orbit faster,” said Clarkson. He compared it to looking from Boston at cars driving in Los Angeles. “Cars in a city in Kansas will be in the way. But they will pass by faster against the background of Los Angeles, and you can use this speed to separate the two.”

In this way the team isolated 12,762 bulge stars. At least 18 to 37 of them are suspected to be blue stragglers. To confirm this, scientists will look for signs of lithium, carbon and oxygen depletion — chemical signatures of mass transfer. Clarkson said that a blue straggler’s spin period could also indicate if it evolved from a merged binary pair.

Clarkson’s team, however, did not use their data to estimate the total number of blue stragglers in the entire galactic bulge. “What we saw is only a pencil beam,” Clarkson said: a sample along one narrow line of sight. “We did not want to use this to make a prediction for a larger population of stars.” So the bulge's exact makeup is still not known with complete precision.

5

5

Comments

William Bartish

June 10, 2011 at 7:18 pm

lately, when I open these newsletters, there is a string of red hyperlinks along the right side of the text. These hyperlinks are repeats of links available for the asking. I find it hard to read the text through the red links and have to copy and paste to MS Word to read it. This appears to have started about 2 or 3 weeks ago, perhaps longer. There doesn't seem to be a reason for it, but it makes reading the newsletters discouraging.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

GeoffB

June 11, 2011 at 4:47 am

The articles read fine for me. I suspect the problem lies with your browser. Did you, 3 weeks ago, change, upgrade or update the browser or install an add-on? If so that could be where the problem lies. If not then it may have been an automatic update. If you cannot pin down the problem then I suggest you reinstall your browser.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Joe

June 11, 2011 at 10:49 am

I have had the same problem for the past few weeks. I'm using Firefox browser.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Michael

June 16, 2011 at 8:54 pm

About a month ago, I upgraded to new Firefox 4, and found it to be regularly crashing and all sorts of other errors. I changed to Google Chrome and it's brilliant. Try that.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Michael C. Emmert

June 30, 2011 at 3:25 pm

I have an interest in decaying solar systems and have modeled what happens when you increase the mass of our gas giants (the system falls apart immediately). It's possible we see so many blue stragglers because the binaries originally had planets, either separately or orbiting the common center of mass. I think this is more likely that close encounters with other stars and much more likely than angular momentum being transferred to some thin gas.

Modeling what happens when a small main-sequence star eats a large gas giant planet is a bit beyond what I can do. Somebody a little farther along than I am might investigate this.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.