With its battery power failing, Philae became the "little lander than could" and managed to return results from all 10 of its science instruments before slipping into hibernation.

If everything had gone according to a carefully constructed plan, the European Space Agency's Philae spacecraft would have descended from mother ship Rosetta, dropped onto its flat, wide-open landing site on Comet 67P/Churymov-Gerasimenko, relayed a rush of findings about the comet's structure and composition, and then basked in enough sunlight to continue operating for several weeks.

ESA / OSIRIS team

But space exploration is never easy, as engineers and scientists at ESA's control center in Darmstadt, Germany, learned this week.

Troubles began when Wednesday when the lander made a pinpoint landing on Agilkia, the Sun-drenched landing site on the "head" of the twin-lobed comet. But two systems designed to anchor the craft in the ultra-low gravity — a downward-pushing thruster and two harpoons — both failed. As a result, Philae bounced not once but twice, coming to rest hundreds of meters from its intended location.

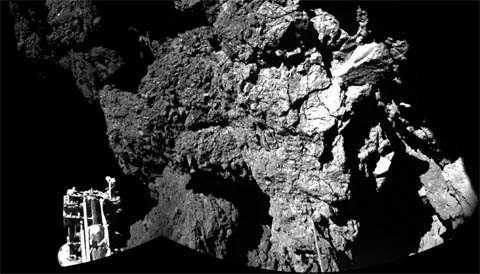

Initial images returned to Earth showed the lander wedged in rugged terrain and deep in shadow from a nearby cliff, its legs angled awkwardly and canted some 30° from horizontal. And yet, the lander was undamaged by by this roller-coaster arrival, ending up with its radio antenna pointed skyward.

ESA / CIVA team

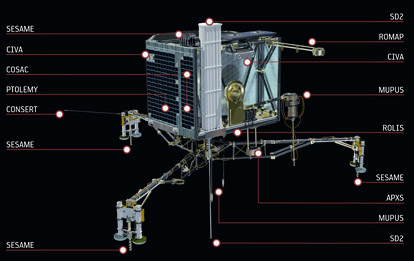

Getting Philae to perform as planned immediately became a race against time, made more intense because the windows of contact with Rosetta were intermittent. The lander's initial surface contact automatically triggered the start of data-gathering activities — yet for the next two hours Philae was airborne, making a 1-km-high arc above the nucleus. And the final, precarious perch made it risky to deploy the lander's mechanical probe, X-ray spectrometer, and sampling drill.

Worse, the clock was ticking. Philae was designed to complete its primary activities within 64 hours, using only the power from an on-board battery. Extended operations could follow if small solar-cell panels provided enough power. But the cliff's deep shadow exposed the landed only to 1½ hours of sunlight during the comet's 12.4-hour rotation, and some panels were pointed toward the cliff.

The Little Lander That Could

Back on Earth, the mission team worked frantically to send up new commands that would salvage as many of the scientific objectives as possible. The drama intensified the morning of November 14th when a communication session with Rosetta ended at 9:58 Universal Time, just as the drill was being deployed. Some feared the battery would die before contact could be reestablished 12 hours later.

ESA / ATG medialab

But when Rosetta returned to view, radio contact resumed at 22:19 UT. Still alive, Philae immediately started relaying findings from all 10 of its instruments. Back on Earth, engineers watched helplessly as the battery voltage plummeted. The final measurements came from Ptolemy, an instrument designed to measure ratios of atomic isotopes. After 75 minutes, the transmission ended as Philae slipped into electronic hibernation.

During the frantic final communication session, the lander's various instrument groups provided moment-to-moment status in a flurry of tweets. Here's one from the SD2 (sampling drill) team: "Preliminary checks show we operated nominally, no time outs. Hopefully we caught the comet sample ever." However, as of November 19th, mission scientists were uncertain whether a sample really had been obtained.

Although the lander operated for nearly 57 hours, short of the hoped-for duration, it managed to return all the results from its final sequence of measurements. There was even enough juice to rotate the lander's body about 35°, to reposition the solar-cell panels to receive more direct sunlight. However, attempts to reestablish communication the next day didn't succeed.

"It has been a huge success," exulted a weary Stephan Ulamec, lander manager for the German aerospace company DLR, which oversaw Philae's construction. "Despite the unplanned series of three touchdowns, all of our instruments could be operated and now it's time to see what we've got."

ESA / ATG medialab

Some of the first announced results are coming from the surface probe called MUPUS (Multipurpose Sensors for Surface and Subsurface Science). The team reports that the wall that looms next to the lander exhibited wide day-night temperature swings, hinting that it's made of a fluffy substance like cigar ash — perhaps a mix of tiny mineral and organic grains.

But there was nothing fluffy about the ground under the lander that the MUPUS sensor "pen" tried to penetrate. Initial attempts failed, despite using three progressively higher power settings for the instrument's electromechanical hammer. Then the team activated a fourth "desperation" mode that exceeded the hammer's design specifications. But it couldn't break through either, and the hammer broke after 7 minutes. The team estimates that the surface hardness is at least 2 megapascals, either very solid ice or perhaps rocky.

Some other early results are summarized in this DLR press release.

Another Day in the Sun?

Conceivably, Philae will again receive enough sunlight — perhaps weeks or months from now as the comet's "seasons" change and the sunlight intensifies — to recharge its battery and return to operation.

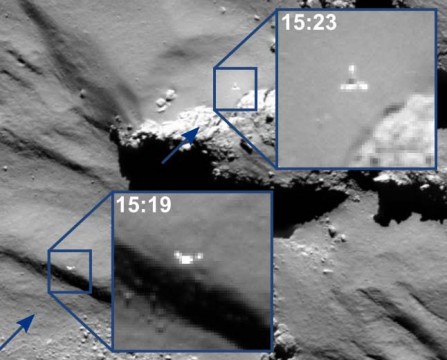

ESA / OSIRIS team

Meanwhile, the team is still searching for Philae's exact resting place. A sequence of high-resolution images from Rosetta were fixated on the planned landing location and missed the likely endpoint along the rim of a broad crater. For now, Rosetta has moved to a somewhat higher orbit, 20 miles (30 km) above the comet, but it will move in closer on December 6th. Until then engineers hope to use a series of radio transmissions from CONSERT, a radar sounder aboard the lander, to triangulate to the final location.

ESA managers have yet not announced when Philae's initial findings will be presented. For now they are no doubt catching up on lost sleep, happy that they've made the most of a bad situation — and, of course, having made the first-ever soft landing on a comet.

Read all about the Rosetta mission in Sky & Telescope's August issue.

5

5

Comments

Joe Slomka

November 16, 2014 at 5:51 pm

Kelly,

Was this ESA's first attempt to land something?

I know they launched a lot of spacecraft, but I don' t remember any landers.

Clear Skies

Joe

You must be logged in to post a comment.

November 21, 2014 at 5:49 pm

Hi Joe,

no, it was not the first attempt for ESA to land something.

In 2005, the lander Huygens from the probe Cassini-Huygens has landed on Titan.

But it seems more difficult to land on a comet due to the very weak gravity.

Josh.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

chrfrde

November 23, 2014 at 1:04 pm

There was also the failed attempt to land Beagle 2 on Mars as part of the Mars Express Mission.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Kevin

November 22, 2014 at 1:47 pm

Well done ESA! At least you got some of the data you were hoping for. The lessons learned from the Rosetta/Philae mission will dramatically increases the chances for 100% success on your next mission. At least you know that your spacecraft can take a pretty good hit and still keep working! Thanks for the cool pictures--they rival the excitement of our first view from the surface of Venus provided by the Soviet Union's Venera spacecraft.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Faye_Kane_girl_brain

November 27, 2014 at 1:44 am

Too bad about the harpoons and bounce, but, still, this was really cool! The best part (other than the science) was staying up all night with other people in the world talking excitedly, enhancing the latest images ourselves, and waiting for the next event. It was like a big pajama party for smart people. It made me feel like I had friends.

The Curiosity landing was like that, too. For that matter, so were the other Mars rovers, and Titan. Just remembering them makes me happy.

We'll never have another Apollo 11, but I want more. The next one will be July, at Pluto. But it might not be as exciting because it's so far away that it can only transmit data at 600 baud(!) In fact, it will take 9 months to transmit all the data. I can't imagine why they didn't put more of the aptly-named plutonium in the power generator. Then they could send a decent signal.

I hope the first thing on it's transmit list is an image!

—faith

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.