A physicist has incorporated a quantum mechanical idea with general relativity to arrive at a new alternative to black hole singularities.

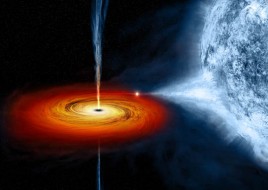

NASA / CXC / M.Weiss

What do you get when you cross two hypothetical alternatives to black holes? A self-consistent semiclassical relativistic star, according to Raúl Carballo-Rubio (International School for Advanced Studies, Trieste, Italy) whose recently published results in the February 6th Physical Review Letters describe a new mathematical model for the fate of massive stars.

When a massive star comes to the end of its life, it goes supernova, leaving behind a dense core that — according to conventional thought — continues to collapse to form either a neutron star or black hole. To which fate a particular star is destined comes down to its mass. Neutron stars find a balance between the repulsive force of quantum mechanical degeneracy pressure and the attractive force of gravity, while more massive cores collapse into black holes, unable to fight the overwhelming pull of their own gravity.

Repulsive Gravity

Now, Carballo-Rubio adds an extra force into the mix: quantum fluctuations. Quantum mechanics has shown that virtual particles spontaneously pop into and out of existence — the effects can be measured best in a vacuum, but these fluctuations can happen anywhere in spacetime. These particles can be thought of as fluctuations of positive and negative energy that under normal conditions would cancel out. But the extreme gravity of compact objects breaks this balance, effectively generating negative energy. This negative energy creates a repulsive gravitational force.

“The existence of quantum [fluctuations] due to gravitational fields has been known since the late 1970s,” explains Carballo-Rubio. But physicists didn’t know how to take this effect into account in collapsing stars.

Carballo-Rubio derived equations that combine general relativity and quantum mechanics in a way that accounts for quantum fluctuations. Moreover, he found solutions that balance attractive and negative gravity for stellar masses that would otherwise have produced black holes. Dubbing them “semiclassical relativistic stars,” these compact objects do not fully collapse under their own weight to form an event horizon, and are therefore not black holes.

Hybrid Star

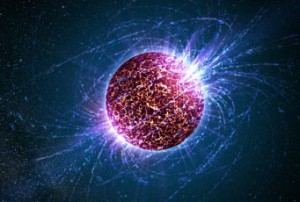

Casey Reed / Penn State University

Interestingly, Carballo-Rubio’s semiclassical relativistic stars bear hallmarks of previously proposed black hole alternatives: gravastars and black stars.

Gravastars and black stars also consist of ordinary matter and quantum fluctuations. But when these ideas were first conceived, equations incorporating quantum flluctuations were not yet known, so theorists Carballo-Rubio’s stars, on the other hand, emerge naturally from a consistent set of equations based on known physics.

Gravastars and black stars are structured differently: In gravastar cores, large quantum fluctuations push ordinary matter outward to form an ultra-thin shell at the surface. Black stars, on the other hand, balance matter and the quantum fluctuations throughout their structure.

Carballo-Rubio’s stars are like a hybrid of the two previous ideas. “On the one hand, both matter and the quantum [fluctuations] are present throughout the structure, as in the black star model,” he says. “On the other, the star displays two distinct elements, namely a core and an ultra-thin shell, as in the gravastar model.”

The Question of Stability

Whether these hybrid stars exist in the real world is a matter of debate. Carballo-Rubio’s solutions do not incorporate time, so it isn’t clear if a such a star would remain stable or rapidly morph into something else . . . like a black hole.

“Equilibrium solutions can be found for a pen standing on its tip,” remarks relativistic astrophysicist Luciano Rezzolla (Institute of Theoretical Physics, Germany). “Such a solution is obviously unstable to small perturbations.”

However, if Carballo-Rubio can show that his semiclassical relativistic stars are indeed dynamically stable — which he will start work on next — the next generation of gravitational wave observatories should offer the level of precision necessary in the coming decades to distinguish unconventional compact bodies from black holes, potentially providing evidence to support the existence of this new type of star.

0

0