The diversity of known exoplanets just continues to grow. Is there any kind of star that can't have planets?

The latest interesting find, astronomers announced today, is a body with at least 1.25 Jupiter masses orbiting the post-red-giant star HIP 13044 in Fornax, 10th magnitude and 2,000 light-years away.

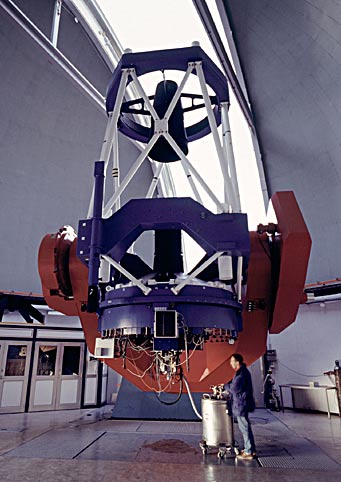

The 2.2-meter MPG/ESO telescope, at the European Southern Observatory in La Silla, Chile, can feed light to a high-resolution planet-hunting spectrograph to monitor stars for signs of gravitational wobbling. The planet of HIP 13044 may be its strangest find yet.

ESO / H. H.Heyer

The planet was found by the radial-velocity wobble that it induces in the star. From the planet's fast, 16.2-day period, it's clear that it at the inner end of its elliptical orbit it comes within a stellar diameter of this unusually large star's surface. The star is yellow and lies on the "horizontal branch" of the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram, meaning that it has already gone through its first excursion to red-gianthood and has shrunk since then. Apparently the planet was farther away during the star's time as a red giant and has worked its way in closer since then, perhaps by a tidal interaction. Otherwise it would have been swallowed.

The planet is unique in two additional ways. Its star has the lowest metallicity (fraction of heavy elements) of any host star yet known. One of the first trends discovered among exoplanets was that the higher a star's metallicity, the more likely it is to have discoverable worlds. But if there's any cutoff on the low-metallicity end, beyond which a star cannot form planets at all, astronomers have yet to find it.

The third remarkable fact is that this system didn't even originate in our Milky Way galaxy. The star is on a high-velocity trajectory that pegs it as member of the "Helmi stream," a swarm of stars that originally belonged to a dwarf galaxy that fell into the Milky Way about 6 to 9 billion years ago and has not quite dispersed beyond recognition.

“This discovery is part of a study where we are systematically searching for exoplanets that orbit stars nearing the end of their lives,” said Johny Setiawan (Max Planck Institute for Astronomy), who led the research. “This discovery is particularly intriguing when we consider the distant future of our own planetary system"; the Sun will become a red giant in about seven billion years.

Any planets that were closer to HIP 13044 may have been consumed already. “The star is rotating relatively quickly for a horizontal branch star,” said Setiawan in an ESO press release. “One explanation is that HIP 13044 swallowed its inner planets during the red-giant phase, which would make the star spin more quickly.”

The discovery team's paper, "A Giant Planet Around a Metal-poor Star of Extragalactic Origin," appears in today's edition of Science Express. It may eventually become available online.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.