A new website shows how light pollution spreads around the globe — using data gathered by its users.

Hundreds of millions of artificial lights illuminate our planet at night — and unfortunately the atmosphere above it. Astronomers have coined the term "skyglow" to describe a phenomenon that not only makes the stars disappear but has also become a problem for nocturnal life and human health.

The ongoing global transition to LED lighting can make the sky even brighter or — used with care — improve the situation. Exactly where we are heading is an open question; the answer will most likely determine the fate of our night sky. Satellites alone won't be able to answer it; measurements from the ground are needed.

For the past decade, citizen-science initiatives like Globe at Night have amassed tens of thousands of skyglow measurements made visually by amateur observers worldwide. These provide valuable aid for researchers trying to understand and quantify the subtle death of starry skies.

Jeremy White / NPS

One of them is Chris Kyba, a Canadian physicist who in 2013 initiated the Loss of the Night app project. Using a simple app, observers around the world make observations of sky brightness by determining the number of visible stars in the night sky then send in those results. Other tools, such as the Dark Sky Meter app, measure the sky brightness more directly using your smart phone's camera. Sky Quality Meters are hand-held devices designed specifically to take brightness readings.

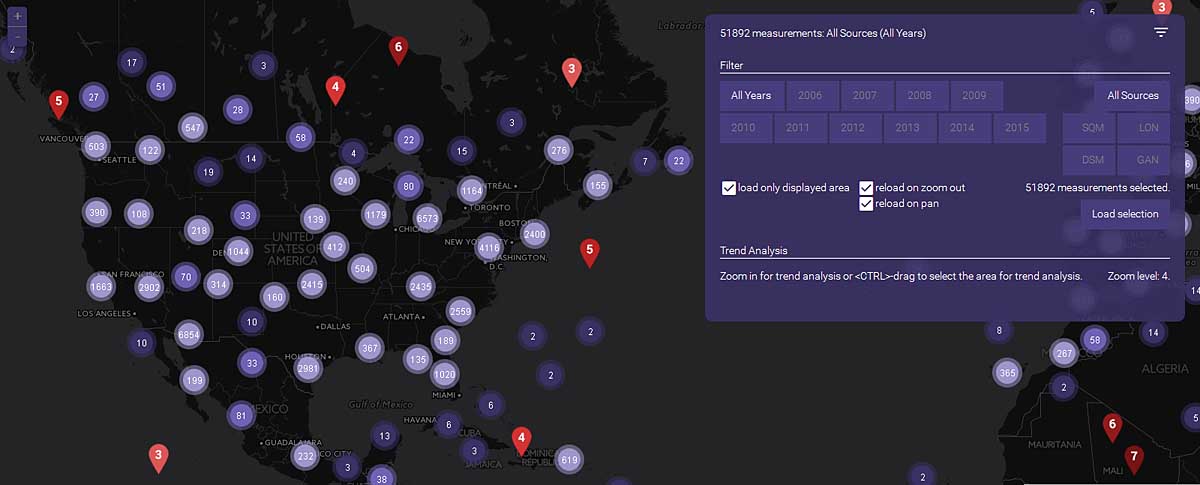

Thousands of measurements have been submitted over the years, but so far most of these data have only been available to professional researchers. Now Kyba has partnered with the company Interactive Scape GmbH in Berlin to develop a web-based application called My Sky at Night. This portal makes available data from the Loss of the Night app and two other citizen-science projects that monitor skyglow.

myskyatnight.com

More Than Just "Data Gatherers"

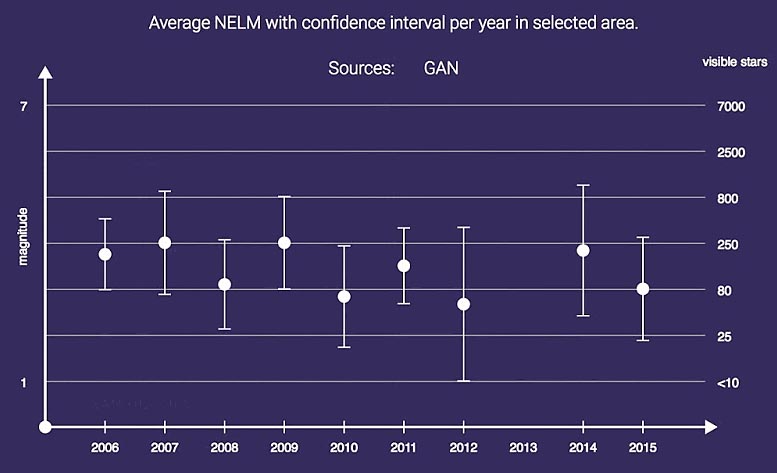

The goal is no longer for the participants to merely collect measurements. Instead, the new web-based platform offers tools to visualize and analyze those data. Now amateur and professional scientists can navigate, view, and download the findings, and then perform their own analyses directly on the site using open-source code. Users of the Loss of the Night app can also create a profile to view their own data. The project, led by the German Research Centre for Geosciences and the Leibniz-Institute of Freshwater Ecology and Inland Fisheries, invites interested people from all over the world to examine changes in their night sky.

The best maps of global light pollution undoubtedly come from orbiting satellites, like NASA's Suomi-NPP or the U.S. military's DMSP orbiters. But satellite data are only of limited use to research because they measure the light emitted directly upward — not the skyglow experienced on the ground by humans and other creatures.

A further complication is that the most current satellites are not sensitive to the blue part of the visible spectrum. Yet right now most outdoor LED lighting emits a large portion of its light at these short wavelengths. Research shows that blue light creates the most skyglow and is most disruptive to nocturnal environments.

myskyatnight.com

Will the current transition to LEDs in public lighting reduce skyglow (because light can be directed to the ground more easily) or increase it (because of all that blue-rich light)? It's a question not yet answered. However, thousands of towns and cities on this planet are currently changing their public lighting or are planning to do so in the near future. Also concerning is the temptation to install higher-output fixtures because LEDs are so energy efficient, making our nighttime environment even brighter than before. Once installed, new lighting fixtures will remain in place for decades.

To monitor these ongoing changes in lighting, observations from the ground are more important than ever. "The data from these observations are crucial for our science," Kyba says. "We urgently need them to evaluate how skyglow is changing worldwide." By introducing My Sky at Night, Kyba hopes you'll contribute to that effort.

You can also fight the spread of light pollution by joining the International Dark-Sky Association. Annual memberships are $35 — a modest investment that will help preserve the night sky.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.