The Orion Nebula hosts a well studied star cluster, the gold standard by which astronomers measure all other clusters. New research suggests that this benchmark might need to be revised.

To amateur astronomers, the Great Orion Nebula (also known as M42) is one of the sky’s most accessible and rewarding targets. It’s barely visible to the unaided eye in a dark sky as a fuzzy patch in Orion’s Sword. With a small telescope you can travel deep into the nebula’s core, set alight by four dominant blue-white stars called the Trapezium.

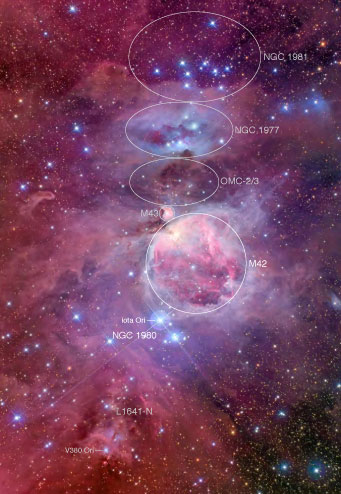

This image illustrates the many overlapping groups of young stars in the Orion Nebula region, some of them still partially hidden by veils of dust and gas. Alves & Bouy find that M42, the nebula's central star cluster, is contaminated by stars from the foreground cluster NGC 1980.

Alves & Bouy

To researchers, M42 is one of the most thoroughly studied objects at all wavelengths, with observational records dating from the invention of the telescope 400 years ago. At a distance of 1,400 light-years, it’s the closest site of energetic massive-star formation. Now, with the help of telescopes like the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope (CFHT), Calar Alto Observatory, and the Spitzer satellite, João Alves (University of Vienna, Austria) and Hervé Bouy (Centro de Astrobiología, Spain) have traveled even deeper to take an accurate census of all the nebula’s stars, numbering in the thousands.

M42 contains several star clusters burning away at the thick veils of gas and dust. The central Orion Nebula Cluster is the most familiar and includes the Trapezium. It has set the benchmark for astronomers’ understanding of how stars form in massive clusters.

But it turns out that membership in the ONC has been overestimated. Alves and Bouy have published a study in Astronomy & Astrophysics showing that as many as 20% of its assumed members actually belong to the closer NGC 1980 cluster, which is centered around Sigma Orionis ½° to the south.

Contamination by foreground stars “has long been a concern,” says Charles Lada (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics), who was not involved in the study. “It has been known for almost half a century that there must be some overlap between the young cluster population and young foreground stars.”

Dust as Decontaminant

The Orion stellar nursery has been churning out stars for the last 10 million years in bursts lasting a couple million years apiece. As a result, many overlapping groups of young stars punctuate the Orion Nebula’s region, and the uncertainties in their distances mean that astronomers have a hard time deciphering their three-dimensional positions.

Alves and Bouy overcame that difficulty using dust. Dust blocks visible light in a biased way, scattering blue light while letting red light through. (That’s why sunsets are red and skies are blue.) So when Alves and Bouy sorted stars near the Orion Nebula by reddening, they were also sorting by distance — more distant stars tend to be behind more dust.

Using dust reddening as a proxy for distance, Alves and Bouy found a distinct population of stars lying in front of the ONC. Their properties, such as their spread in ages and brightnesses, set them apart..

The authors suggest that the measured properties of the ONC, a benchmark of star-formation regions, will have to be revised. Once the ONC catalog is “cleaned” of false members, Lada says, adjustments may have to be made to the details of star-formation theories. Other results, such as the recent simulation that grew a massive black hole at the center of the nebula, are only marginally affected by the contamination.

For more, see the researchers’ paper: "Orion Revisited: The Massive Cluster in Front of the Orion Nebula Cluster".

18

18

Comments

Henrik

October 22, 2012 at 9:39 am

An excellent demonstration of the Popperian dogma that no scientific theory is ever "written in stone", only not yet falsified or falsifiable. Since I'm merely a linguist and historian, is Scientific Philosophy part of the curriculum in physics/astronomy?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Joe Stieber

October 22, 2012 at 9:48 am

A minor correction. NGC 1980 is centered on Iota Orionis, not Sigma Orionis (the latter is roughly 3 degrees north of M42).

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Josh Thum

October 22, 2012 at 3:05 pm

This is a truly spectacular nebula. I love seeing pictures, but I really want to see it on my own. I have an ETX-90 from Meade, and this would be an ideal sight to see. Yet every time I try, I can never see M42 through it. I already can't figure out how to align it, but I know where M42 is by heart, yet still I can't see anything. I use a 26mm lens, and sometimes try a 9.7mm lens, yet none work. I don't know if it's aperture, or... Can anyone help me out a bit with this? Oh, and for the record, i'm 12.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bruce

October 23, 2012 at 8:52 am

Come on ya'll, someone needs to encourage this young man’s interest in this science that we all love. Josh, I’m not much of a hands on amateur astronomer, but I’ll try to help if I can. I share your appreciation for M42. It’s a wonderful first target for your scope at night, but since you’re having problems seeing it I suggest you make sure your scope is properly set up during the daytime. Are you able to focus your scope on some distant object on the horizon using your larger 26mm eyepiece? If so, fine, but without moving your scope now look though your finderscope. Compare the views. Are the crosshairs of the finder at the very center of the view you see in the main eyepiece? They might not be, and this could very well be the cause of your problems. Adjust the aim of the finderscope using the setscrews. This may take some time, but you’ll soon learn how little turns of these setscrews move the crosshairs of the finder. Then when you feel that the finder and the main scope are aimed at the same thing change to the 9.7mm eyepiece and repeat the above procedure until the views are targeted on the same point. Carefully (don’t over-tighten which could strip treads) lock the finder down. Is the finder still aimed correctly? If not, re-aim. You’re goal is to have your finder locked in place so that it won’t shift out from the center of your view even as you move your scope around. Now your scope is properly aligned and ready to be used at night. With the larger eyepiece installed find your target object in the finder and you should be then able to focus on it easily with the main scope’s view. Look at M42 and tell us what you see. Can you see the four stars of the Trapezium in your smaller eyepiece? We would all like to read about what you can see, because it will remind us of the fun we had when we saw this for the first time ourselves!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Josh

October 23, 2012 at 2:39 pm

Okay. I'll attempt to do that, the problem is it is very rainy outside. My mom also signed me up for this thing at Yerkes Observatory in Wisconsin. I'm in 7th grade, and it's for 9-12 graders, but they accepted me in. I'll try and get some more advice there, too, but thanks a lot for the help, Bruce! I will post my results too.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Josh Thum

October 23, 2012 at 2:41 pm

I also knew that the viewfinder was not aligned correctly. I just wasn't sure how to fix it. It was always a bit up and to the left. I'll try and fix that.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Josh Thum

October 23, 2012 at 2:47 pm

Except the thing is, my model of the telescope's viewfinder is a red laser beam dot thing. So in daylight it's impossible to see it.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Henrik

October 24, 2012 at 7:17 am

Josh, I had to look this up. Your ETX-90 has a focal length of 1250 mm, yes? So with the 26 mm eyepiece, the magnification is ~50x (the 9.7 mm yields about 130x and is well-nigh useless for viewing nebulae and galaxies). Since M42 is a large, diffuse object, it's best viewed at as low magnification as possible, in the case of your scope and your eyes 90 mm aperture divided by the width of your fully dark-adapted pupil at 8 mm or 11 x. What I think may have happened is that you have been looking at it but at the magnifications you're using, the light from the nebula has been "stretched so thin" that you're barely able to see it. Visually, M42 is nothing like photographs, a mere blob of diffuse light. But you should be able to both spot the Trapezium and possibly resolve some of the stars as double. Best luck!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bruce

October 24, 2012 at 12:27 pm

Henrik’s comment is right Josh. When you learn the math behind what he is saying you will understand much about telescopes. I’m sure the program you are about to share in at Yerkes will allow you to understand the reasons for what Henrik wrote. (Henrik, I hope you don’t mind my asking, but since my grandmother was Dutch and her name was Hendrika, I was wondering, are you Dutch too?)

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Josh Thum

October 24, 2012 at 2:34 pm

Thanks Henrik. But I already knew that it wouldn't look like that, I know those pictures are at infrared wavelengths. And at Yerkes, we just listened to a presentation of the studies this one professor had in Antarctica. Next time we're going to look through a 60-feet telescope. (I've looked through it before, i'm friends with one of the professors there). My mom says if I get to know the professors it will be easier to get into the University of Chicago.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

M42

October 24, 2012 at 3:32 pm

Err... maybe not infrared wavelengths, rather a few different pictures put together to make one...

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Josh Thum

October 25, 2012 at 5:40 pm

I got the viewfinder aligned and I got the telescope aligned! I can see stars and planets through it, but I can't see nebulas or galaxies through it. I'm only using the 26mm too.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Eugene Dees

October 26, 2012 at 2:43 pm

I'd like to suggest a Telrad ? Saved me the most hassle ever!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Anthony Barreiro

October 26, 2012 at 8:44 pm

Josh, large diffuse nebulas like M42 often look better through binoculars than a telescope. If you have a pair of binoculars and a reasonably dark sky, give it a try. 8x42, 7x50, or 10x50 are good binoculars for skywatching.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Josh

October 27, 2012 at 6:54 pm

Well, I have two pairs of binoculars. One is sadly missing, I know it was pretty good. The one I have now is 12x32.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Keith

October 28, 2012 at 10:20 am

Josh, it's great to see your interest in astronomy and to see the interest of so many others in having it continue to grow. My two cents - for 'budding' astronomers it can be very hard to get a sense of scale between what you see in magazines and through the eyepiece. Many of the objects you will be interested is seeing are quite large relative to what you will see through your eyepiece. Often times it can be helpful to have a more 'studied hand' verify that what you think you are looking at, is indeed what you are looking at. Try to find a local astronomy club or take your scope to Yerkes and see if you can get someone to help you. I recall struggling from my suburban driveway to find M57 - I was only successful when 'it' happened to fall into the narrow break between my house and my neighbour's. The streetlights were blocked and the faint light was now visible. Having found it once, I can now find it in more challenging places. Once centered, I've been able to show others although for 'first timers' it requires some patience and a little bit of skill (using averted vision). As for M42, the phototgraphs collect so much light that the trapezium cluster (at the core of the nebula) is not visible - it is fairly small but does form a trapezoid. This makes it difficult to confirm that you are seeing what you think you are seeing (or should be seeing). Key learnings - the darker your site, the easier to see the faint fuzzies, and a helping hand can go a long way to easing some of the frustration we all work through.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Josh

October 28, 2012 at 5:30 pm

Okay. Also, where I live is near Chicago, so there is a lot of light pollution. I can barely see the bottom-most star in Cassiopeia. I went outside last night, it was fairly clear, except for a few patchy clouds here and there. I know NGC2024 is literally right on top of that star, or behind it, and when I looked at the star, I saw a star and a star only. That kind of disappoints me. Is the reason I'm not able to see nebulas, or even fuzzy patches, because of light pollution? That's what I think.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Josh Thum

February 11, 2014 at 9:00 pm

Well, here I am, two years later. An untimely comment indeed.

http://spaceweathergallery.com/indiv_upload.php?upload_id=94158

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.