Astronomers have found a third planet circling a pair of stars in the Kepler 47 system.

NASA / JPL-Caltech / T. Pyle

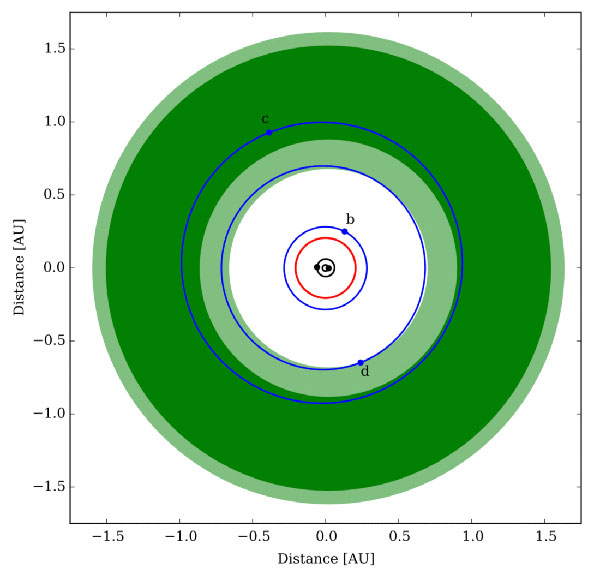

Kepler 47 just got bigger. Jerome Orosz (San Diego State University) and colleagues announced in the May issue of the Astronomical Journal that the “Tatooine” system, with two previously known planets orbiting two stars, has a third planet. The system is 3,340 light years away in the constellation Cygnus and, so far, it’s the only one known to host.multiple planets. The binary pair consists of two main-sequence stars, one like our Sun and the other a red dwarf. The new planet, Kepler 47d, orbits between the two planets discovered earlier — in fact, all three of them orbit the stars so closely, they could fit inside Earth’s orbit around the Sun.

Astronomers once thought that circumbinary planets – worlds orbiting a pair of stars – couldn’t exist because the dynamic interplay of dual stellar gravities would rule out stable planetary orbits. The discovery of Kepler 16b about 8 years ago dispelled that idea and recast some models of planetary behavior. Now, the confirmation of a multi-planet system could stretch those models even further.

NASA / JPL Caltech / T. Pyle

The existence of the Kepler 47 system suggests that gravitational interactions limit the sizes of circumbinary planets, perhaps explaining why rocky planets are far less likely to be found around binaries. When planets form within the dust-and-gas disk surrounding young stars, their interactions with the disk cause them to migrate inward. The two stars’ competing gravitational forces end up casting most of the smaller planets out of the system, explains coauthor Nader Haghighipour (University of Hawai‘i). Giant planets, on the other hand, continue migrating inward and ultimately crash into the stars. Only intermediate-size planets remain.

Orosz et al. / Astronomical Journal 2019

Kepler-47 also demonstrates that circumbinary systems can fill up with planets on stable orbits. “I think that the big breakthrough of this,” says David Martin (University of Chicago), “is that it’s what we call a packed system.” Martin, who was not involved in the Kepler-47 research, explains: “You couldn’t put any other planets between these three and have the system survive. It’s important for understanding how planets form.”

Transits Are Tricky

All three planets around Kepler 47 were discovered with NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope. Launched in 2009, Kepler searched for exoplanets via the transit method – sensing small changes in the brightness of starlight as planets passed in front of their suns.

Finding exoplanets by their transits can be hard. They have to be big enough to measurably dim the starlight as they pass. Then, the tilt of their orbital plane must be small enough relative to Earth to allow observers to see the periodic transits of the planets across the face of their stars. Orbital planes of circumbinary planets are further complicated by wobble; they vary slightly over time. “For every [circumbinary] planet you see, there are about eight or nine that you miss,” says study coauthor Bill Welsh (San Diego State University).

A Different Kind of Search

Data on the Kepler 47 system only extended through 2013, but NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) launched in 2018 to pick up observations. TESS will be in position to look at Kepler 47 this summer, and researchers are excited to see new data on the system after a five-year gap. TESS is designed, however, to image larger swaths of sky than Kepler, looking for planets around the 200,000 closest stars. Its search will offer a new way to study circumbinary systems.

“TESS is going to be looking at hundreds of thousands of binary stars,” says Welsh. “Kepler got around 3,000 but TESS is going to add a few hundred thousand. The goal with TESS is to start to do statistics, to look at patterns and trends among these systems.”

One of the goals is to understand how planets can form in the gravitationally unstable environment around binary stars, and the ongoing search is giving astronomers plenty of material to work with. “We’re not only finding planets around binaries, we’re finding them at a rate comparable to single stars,” notes Martin. “It seems that nature likes living on the edge.”

1

1

Comments

fif52

April 26, 2019 at 7:00 pm

An excellent articule, keeping use upto date. Hopefully they shall find more planets. Quite comparable to Tatooine with its atmosphere obscuring the surface and inside the habitable zone, even if dry suitable for life.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.