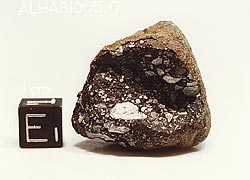

A meteorite from the Moon, collected on the Allan Hills ice field in Antarctica. The cube is 1 centimeter on a side.

Courtesy NASA / JSC.

It's been 20 years since planetary scientists first realized that chunks of the Moon and Mars were practically falling into their laps as meteorites. And, while thankful for the free samples, they've always puzzled over why these two worlds are represented roughly equally on Earth. To date collectors have snatched up 24 distinct meteorites from the Moon (some of which were found in multiple pieces or paired with other finds) and 28 from Mars.

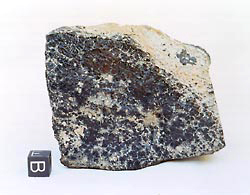

A chunk of Mars: the Los Angeles meteorite, found in California's Mojave Desert.

Copyright 2000 Ron Baalke.

The puzzle arises because the lunar specimens should outnumber their Martian counterparts by more than 100 to 1. For one thing, the Moon's weaker gravity means that a much smaller impact will accelerate lunar debris to escape velocity, compared to the more energetic (and thus rarer) blasts necessary to eject something from Mars. Calculations performed several years ago by Brett Gladman (University of British Columbia) show that, once launched into space, a chunk of lunar rock has about a 50-50 chance of ending up on Earth — 10 times better odds than for an arrival from Mars.

So why aren't the meteorite-rich tracts of Antarctica and Saharan Africa littered with more chunks of Tycho and Mare Imbrium? The answer, according to James N. Head (Raytheon Missile Systems), may be that most of them have simply disappeared over the past 100,000 years or so, eroded to oblivion by wind and water. Head says that most meteorites from the Moon should reach Earth within only about 10,000 years, so if by chance there haven't been any recent lunar impacts, the arrival rate right now will be in a deep lull, and the old ones will be mostly gone.

Martian meteorites, by contrast, take an average of roughly 10 million years to make their way here, ensuring a steadier arrival rate. Long after the most recent wave of lunar rocks are eradicated by weathering, new messengers from Mars will keep trickling in — roughly once per month. Notably, four Martian falls have been witnessed firsthand, whereas no one has seen a piece of the Moon descending to Earth.

But there's a problem with this scenario. Head's scheme, which he presented yesterday at the annual Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, implies that all lunar meteorites should be recent arrivals, and that's not the case. Of the 13 with well-established travel times (determined by measuring their exposure to cosmic rays while in transit), six left the Moon between 500,000 and 9 million years ago. In fact, notes Kunihiko Nishiizumi (University of California, Berkeley), lunar and Martian meteorites share the same basic age distribution.

Nonetheless, Head says, to date the census of the two groups is still "a wash," with 99 percent of the expected lunar meteorites somehow staying out of collectors' hands. Gladman agrees, noting that the near-equal numbers of lunar and martian meteorites "must be a consequence of the finite age of the [Antarctic] ice sheet combined with transfer dynamics that today deliver few meteorites from ancient lunar impacts, but a reasonable flux from larger ancient martian impacts."

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.