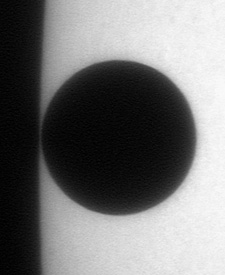

A fog bank created a natural solar filter for this image of the just-risen Sun over Cambridge, Massachusetts. Venus is clearly visible under the clouds, as seen in this image taken through a 70-millimeter refractor.

Courtesy Jessica Dawn Tytell.

People all over the world watched Venus pass in front of the Sun today — a much-awaited event that hasn't occurred since December 6, 1882. The entire 6.4-hour transit was visible from Europe, the Middle East, and most of Africa and Asia. Most of the rest of the world saw a partial transit, with sunrise or sunset interrupting the view.

In Florence, Italy, Sky & Telescope editor in chief Rick Fienberg watched the beginning of the transit with a Sky & Telescope /TravelQuest International tour. He reported, along with many others, that the enigmatic "black-drop effect" — which plagued astronomers' efforts to time the transit in centuries past — was not prominent this time around.

Rick Fienberg captured this image of the transit with an 85-millimeter refractor in white light shortly after second contact from Florence, Italy. Notice the two small sunspots at top right.

Sky & Telescope image: Richard Tresch Fienberg.

"None of us saw Venus take on a distinct teardrop shape," he reported. "Instead, the limb of the planet tangent to the Sun's limb began to get fuzzy, making it difficult to tell when the two limbs were exactly touching."

Even without the black drop effect, Fienberg noted that the timing of second contact was very difficult to pin down. "I overheard another observer trying to call out the exact moment of second contact [the moment Venus gets completely onto the Sun]. He said, 'Now, no now, maybe now? Now! No. . . now!' for nearly a minute. As none of the rest of us could tell the exact moment either, it gave us a new appreciation for the difficulties encountered by our predecessors in timing the contact points during the 18th- and 19th-century transits. It is definitely not easy!"

Observing from a park overlooking the Sky & Telescope offices in Cambridge, Massachusetts, S&T associate editor David Tytell watched as the Sun rose through a fog bank. "What was most amazing was the 'Moon illusion' that occurred at sunrise with the Sun so low on the horizon. Not only did the Sun loom extraordinarily large in the sky, Venus too looked magnified to the naked eye. Later on, when the Sun was higher in the sky, it was much harder to spot the planet on the solar disk without magnification from binoculars or a telescope."

"I thought I was ready for how this would look, but I wasn't," said S&T senior editor Alan MacRobert, observing with friends from a meadow in the Boston suburbs. "It was so much more powerful. Venus looked just gigantic [in a filtered 8-inch reflector at 50x and 110x]. It was a big black hole punched in the Sun. At times I really had a 3-D impression of a black planet hanging in space between us and the Sun. The whole thing was so clean. Pictures just don't convey it."

Three webcam images were combined to reveal this scene at the moment of second contact. This view was taken through the 16-inch f/16 refractor at the Vatican Observatory at the Pope's summer residence at Castel Gandolfo, Italy.

Sky & Telescope photograph: Dennis di Cicco

At the Vatican Observatory in Italy, rain and clouds that had persisted for days suddenly cleared after 4 a.m., and observers watched the transit with "perfect skies and excellent observing conditions," reported S&T senior editor Dennis di Cicco. "Venus is a stunning black spot visible to the naked eye when viewed through a solar filter." Di Cicco noted a complete lack of black drop: "There was no significant effect visible in white light at the time of second contact."

While millions witnessed the event live, those unable to watch directly due to clouds or geography took advantage of broadcasts on television and the Internet. Many webcasts of the transit were unavailable or extremely slow due to high traffic. The European Southern Observatory's webcast site was getting 1,500 hits per second about a half hour after the transit began.

Third contact as seen from the top of Mount Equinox (3,800 feet) in Arlington, Vermont. Here the much-touted 'black-drop' effect is somewhat apparent. This white-light image was captured with a webcam and a 4-inch Maksutov telescope.

Courtesy Andrew Chaikin.

Although transits of Venus today are viewed merely as astronomical novelties, astronomers of the 18th and 19th centuries saw them quite differently. Observing teams mounted expeditions all over the world to record differences in the timing of Venus’s passage across the solar disk. Such timings can be used to triangulate on Venus and calculate the distance to Venus, the Sun, and ultimately the size of the Solar System.

Only one other transit will occur this century, on June 6, 2012. That event will be visible at least in part for most of the world, except for Western Africa and most of South America. Afterward there will be a 105-year wait until the next one, on December 11, 2117.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.