The universe sings to us in gravitational waves, and we're starting to listen. Michelle Thaller discusses the discovery of gravitational waves and their unusual effects in her latest astronomy podcast.

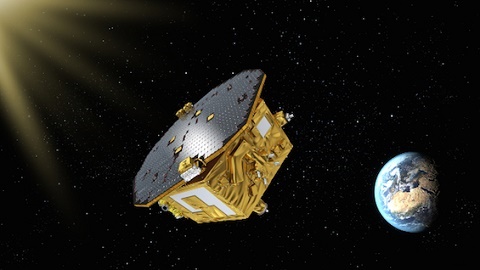

NASA JPL / ESA

Surely one of the most profoundly wonderful and strange ideas in modern physics is that empty space, coupled with time itself, is a thing that can be bent and stretched, and even made to ripple like waves on a pond.

More than 100 years ago, Albert Einstein described gravity as a bending of space and time; anything with mass, from an electron to a supermassive black hole, can bend the universe around it, distorting the measurements of our rulers and clocks in the process. And if this mass happens to move around, spacetime responds to that motion, creating waves of gravity. Incredibly, we exist in a matrix of constantly bending and rippling spacetime.

Luckily for us, it takes a huge amount of energy to generate even a tiny distortion, compared to our human scale. These waves are so small that our most advanced detection devices have just barely been able to tease out signals from one of the most violent events the universe has to offer: two merging, massive black holes. In September 2015, twin detectors that make up the Laser Interferometric Gravitational Wave Observatory (LIGO) shook slightly as the waves from a black hole merger 1.3 billion light-years away reached Earth. This event was the first confirmed detection of a gravitational wave, and by the time it passed us by, the ripple was many, many times smaller than the diameter of a single proton. But that was enough for LIGO.

In this episode of Orbital Path, Professor Jana Levin, a theoretical physicist at Columbia University, tells us the remarkable story about how LIGO came to catch those elusive waves for the first time, turning new eyes, or more accurately, new ears, on to the sound of the universe itself.

If we indeed live in a rippling and undulating universe, are there consequences of gravitational waves we can see, even if the waves themselves were not detected? Marco Chiaberge (STScI) thinks he may have seen just that. Using the Hubble Space Telescope, Chiaberge found a very strange galaxy that appears to be hurling a supermassive black hole out of its core.

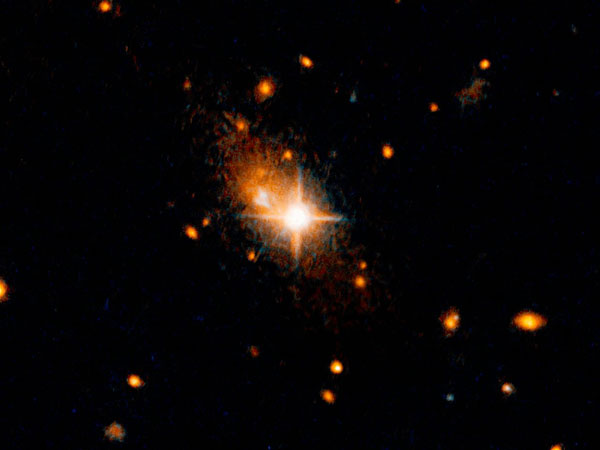

NASA / ESA / M. Chiaberge (STScI / ESA)

Bright, active galaxies are usually powered by black holes millions or billions of times the mass of the Sun in their cores, probably the end result of many smaller black holes colliding and merging over huge timescales. It would make sense, then, that these hugely massive objects would rest right in the center, at the center of mass of their galaxies, everything else spinning around them. But in this case, a black hole with the mass of a billion Suns has been sent careening out of its galaxy at over 4 million mph. Can we all just pause for a moment and consider that? What could possibly have the energy to accelerate a billion solar masses to such immense speeds?

Chiaberge thinks gravitational waves might be the answer. If two huge black holes merge in some rare and unbalanced say, the resulting waves might have gone off asymmetrically, like a bullet fired out of a gun. And the black hole got kicked hard by the recoil.

How else do gravitational waves influence the universe around us? What sorts of exotic objects will we find with the next generation of gravitational wave observatories? We have hardly any idea yet. The universe has been singing to us all along, but only in the last two years have we opened our ears to listen.

Orbital Path is produced by PRX and supported by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation. Don't miss PRX's other science podcasts: Transistor and Outside Magazine.

1

1

Comments

xinhangshen

May 24, 2017 at 5:22 pm

Michelle Thaller, please be aware that Einstein’s relativity theory has already been disproved both logically and experimentally (see “Challenge to the special theory of relativity”, March 1, 2016 and a press release on Eurekalert website: https://www.eurekalert.org/pub…/2016-03/ngpi-tst030116.php).

The most obvious and indisputable experimental evidence, which everybody with basic knowledge of special relativity should immediately understand: is the existence of the absolute time shown by the universally synchronized clocks on the GPS satellites which move at high velocities relative to each other while special relativity claims that time is relative (i.e. the time on each reference frame is different) and can never be synchronized on clocks moving with relative velocities.

Many physicists claim that clocks on the GPS satellites are corrected according to both special relativity and general relativity. This is not true. The corrections of the atomic clocks on the GPS satellites are nothing to do with relativistic effects because the corrections are absolute changes of the clocks, none of which is relative as claimed by special relativity. After all corrections, the clocks are synchronized not only relative to the ground clocks but also relative to each other.

Some people may argue that the clocks are only synchronized in the earth centered inertial reference frame, and are not synchronized in the reference frames of the GPS satellites. If it were true, then the time difference between a clock on a GPS satellite and a clock on the ground observed in the satellite reference frame would grow while the same clocks observed on the earth centered reference frame were keeping synchronized. If you corrected the clock on the satellite when the difference became significant, the correction would break the synchronization of the clocks observed in the earth centered frame. That is, there is no way to make a correction without breaking the synchronization of the clocks observed in the earth centered frame. Therefore, it is wrong to think that the clocks are not synchronized in the satellite frame. Actually, on the paper mentioned above, I have proved that if clocks are synchronized in one inertial reference frame, then they are synchronized in all inertial reference frames because clock time is absolute and universal.

Similarly, all the differences of the clocks in Hefele-Keating experiment were also absolute (i.e., they were the same no matter whether you observe them on the moon or on the space station). Therefore, they are nothing to do with relative velocity caused time dilation as claimed by special relativity. It is simply a wrong interpretation that the differences of the displayed times of the clocks are the results of relativity. The increase of the life of a muon in a circular accelerator or going through the atmosphere is also an absolute change which is the same observed in all reference frames.

The simplest thought experiment to disprove special relativity is the symmetric twin paradox: two twins made separate space travels in the same velocity and acceleration relative to the earth all the time during their entire trips but in opposite directions. According to special relativity, each twin should find the other twin’s clock ticking more slowly than his own clock during the entire trip because of the relative velocity between them as we know that acceleration did not have any effect on kinematic time dilation in special relativity. But when they came back to the earth, they found their clocks had exact the same time because of symmetry. This is a contradiction that has disproved special relativity. This thought experiment demonstrates that relativistic time is not our physical time and can never be materialized on physical clocks.

That is, time is absolute and space is 3D Euclidean. There is nothing called spacetime continuum in nature.

Please update your knowledge to avoid spreading wrong messages to the public!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.