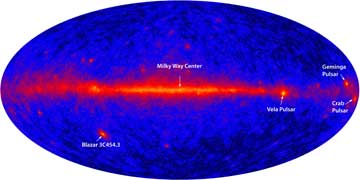

The Fermi Space Telescope's primary instrument, the Large Area Telescope, acquired this image of the gamma-ray sky after just a few days of observation. Click on the image to view a larger version.

NASA / LAT Science Team

Before coming to S&T in early June to become editor in chief, I worked at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center. I wrote press releases and other material to support Goddard missions and scientists. Among my major duties was to promote NASA's next major space observatory: the Gamma-ray Large Area Space Telescope, mission, or GLAST for short. During my time at Goddard I had the pleasure and honor of getting to know some of the mission's leading team members, such as project scientist Steve Ritz, deputy project scientists Neil Gehrels, Julie McEnery, and Dave Thompson, and project manager Kevin Grady.

While I was excited to return to S&T, I felt a sense of letdown to leave Goddard only a few days before GLAST was launched from Cape Canaveral. I missed experiencing firsthand the giddy excitement as team members watched the first data stream down to Earth and seeing their years of labor bear fruit.

I have been following the mission closely since coming to S&T, but I was overjoyed by today’s "coming out party." During an afternoon media telecon, NASA announced a new name for the mission, the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope, and presented first-light science results.

NASA

It's going to take me awhile to get used to calling the mission by its new name and acronym FGST, but the choice of the name "Fermi" doesn't surprise me in the slightest. I did not formally submit one of the 12,000 names in NASA's call for public participation, but I mentioned on numerous occasions that it made perfect sense to name the observatory after the great Italian-American physicist Enrico Fermi (1901-1954), who won the 1938 Nobel Prize for physics. Among Fermi’s many enormous contributions to science, he was the first to suggest a viable means for cosmic particles to be accelerated to near-light speeds. This is exactly the kind of thing that GLAST was built to study.

As I expected, no Earth-shattering science results were announced today. After all, FGST has been in space for less than 3 months, and the first few months of all missions are devoted to turning on and checking out the instruments and other spacecraft systems. But we learned today that the two instruments, the Large Area Telescope (LAT) and GLAST Burst Monitor (GBM), are both working as well as anyone could have expected. In just a few days of observing, the LAT, a wide-field instrument that picks up high-energy gamma rays, has already detected all the persistent sources seen by previous missions. The GBM is detecting about one gamma-ray burst per day, slightly higher than the predicted rate.

Now that I sit on the journalist's side of the fence, I can't wait to cover FGST's discoveries in the years ahead. The spacecraft will probably tell us about how active galaxies accelerate particle jets to speeds approaching that of light, why pulsars pulse, how and where cosmic rays are accelerated, how the central engine works in gamma-ray bursts, and how the Sun generates powerful flares. If we get really lucky, FGST might even detect annihilating dark-matter particles and exploding primordial black holes. And since FGST will be observing Mother Nature at her most extreme energies, if we get really, really lucky, FGST might even unveil new laws of physics.

The FGST's journey has just begun. To learn more about this mission, visit the mission website.

1

1

Comments

Jennifer Morcone

August 26, 2008 at 3:58 pm

A very classy post, Bob. Glad you are still interested in GLAST! The GBM team is a buzz with activity and you are always welcome to come for a visit. Are you planning to attend the Gamma Ray Symposium in October?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.