Say it ain't so! The shock and dazzle of Iridium flares will soon be a thing of the past. Here's how to make the most of seeing them before a new generation of spacecraft replaces the Iridium satellites.

Bob King

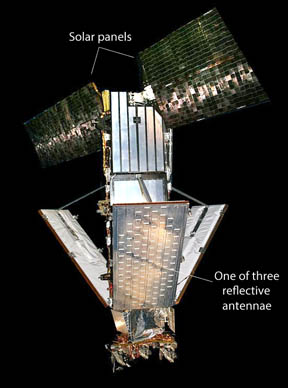

I wonder how many involuntary "Oh my Gods!" have been uttered by observers dazzled by an Iridium flare. Reflective surfaces of other satellites occasionally catch the Sun and temporarily brighten by several magnitudes as they glide across the sky, but there's nothing like the flare produced by an Iridium satellite. Each of the approximately 66 Iridiums in orbit have three door-sized aluminum antennae treated with highly reflective, silver-coated Teflon for temperature control.

When the angle between observer and satellite is just right, sunlight reflecting off an antenna can cause the satellite to surge from invisibility up to magnitude –8.5 in a matter of seconds. If you've never seen one, the searing brilliance may make you recoil instinctively. On rare occasions, flares can reach magnitude –9.5. That's 100 times brighter than Venus!

"On many occasions, I have showed people an Iridium flash. They were all astounded the flares were so bright and could even be predicted." — Leo Barhorst, the Netherlands

Iridium Communications

Iridium spacecraft provide voice and data communications for users around the globe. The name Iridium derives from element number 77 on the periodic table. The satellites' owners originally planned to orbit 77 of them, but settled for 66 and a few spares. Since they were launched in 1998, they've been entertaining skywatchers on a nightly basis.

Thanks to easily available predictions, maps, and phone apps, it's safe to say that Iridium flares have inspired thousands of people to look up at night sky to witness the spectacle themselves.

Iridium Communications

"I have been photographing Iridium flares since 1997 from various parts of the world. In fact, I was the one who first discovered the source of the flares after working with engineers at Motorola that year. I have gone so far as making a bar bet with people, advertising Iridium flares at international aerospace conferences, and emailing predictions to other overseas before there were web pages that allowed easy access to flare times." — Paul Maley, NASA Johnson Space Center Astronomical Society

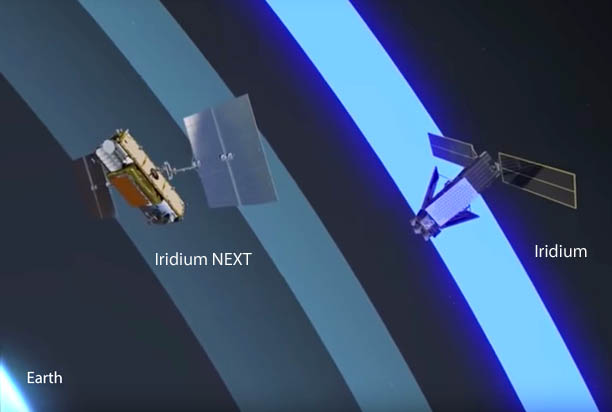

Sadly, that era will soon draw to a close. On January 14th, SpaceX’s Falcon 9 delivered the first 10 of a new generation of Iridium NEXT satellites to low-Earth orbit, starting the process to replace the older units in a maneuver called slot-swapping. While the new birds will provide faster data rates and enhanced global communications, their antenna design is completely different and not expected to produce significant flares.

The first 10 satellites will go through a 90-day test period to ensure that they're functioning nominally, then each new satellite will begin moving to the location of an existing Iridium in the constellation. Once the new satellites are made operational, their older counterparts will be placed in parking orbits. Eventually, most of these first-generation birds will be de-orbited, but a few might remain as spares, according to an Iridium spokesperson I spoke with on the phone recently.

Learn how the old Iridiums will be replaced with the new in this video

The good news for flare enthusiasts, though, is that even in the parking orbits the older satellites should continue to create our beloved flares, at least for a little while longer. It will be interesting to see if either the frequency or brilliance of the glints will be affected by the new orbits.To stay in touch with the antics of both the new and older Iridiums, I encourage you to join the Seesat-l mailing list. The satellite observers there share a wealth of knowledge and enthusiasm.

"Before the EUROSOM 3 (European Satellite Observer Meeting) conference, Edinburgh, Scotland, October 1998, I made predictions of visible satellite passes and Iridium flares. Using Rob Matson's Iridflar program, I predicted a daytime flare during the conference. When it came time for the flare, we all adjourned to the shadow of the observatory and, right on time, we were thrilled to see a satellite in broad daylight. It was the first daytime Iridium flare for many observers." — Jay Respler, Freehold, New Jersey

Iridium Communications

Ten more new satellites will launch in April of this year. After they're tested, they'll replace the next 10 old-timers. With launches expected every 2 months after that, and 66 satellites (plus four spares) to move into place, all the new Iridiums are expected to be positioned and operational by mid-2018. With the new antenna design, bright, naked-eye flares like those we've grown accustomed to are expected to end. No one's sure how luminous the new generation will be, but I'm certain we'll find out soon — little escapes the eyes of the amateur satellite-watching community.

"My first Iridium experience was in 1998. Always interested in viewing satellites, I came across a reference to Iridium flares while looking for information on predictions. My first thoughts were: "What the heck is an Iridium flare?" and "Why would you set one off in space?" Within a week, there was an opportunity to see a –7 flare. It happened exactly as I expected, based on the descriptions I had read. Still, my reaction was "Oh My God." — George S. Williams, Wakefield, Virginia

That leaves about 17 months left of razzle-dazzle and an undetermined amount of time as the older units cool their heels in parking orbits until the lights go out. If you've never seen a flare, don't miss these last opportunities. Heavens Above is one of the easiest sites to get you looking in the right place at the right time.

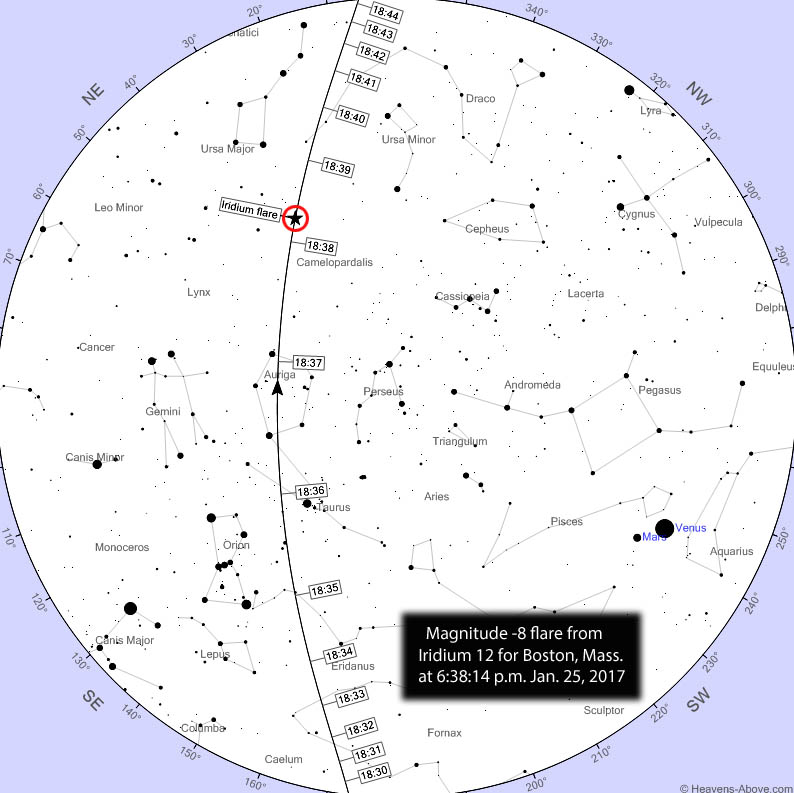

Heavens Above (Chris Peat) with annotations by the author

Just sign in and give it your location, then click the Iridium Flares link under the Satellites heading on the left side of the homepage. A table will pop open with a week's worth of passes that includes pertinent information like brightness, altitude, and magnitude of the flare at flare center, the brightest possible magnitude for a particular pass. Clicking on the date will produce a map showing the flare's path and ground track where the flare will appear brightest. When that path passes near or over your location, you'll see a –8 dazzler. If not, you can use the map to drive to the sweet spot and await the display.

"One of the stranger things I'd seen over the years involved the original Iridium sats, though not a flare. I was observing from North Pole, Alaska back in 1998 at dusk, when I saw a string of five 'stars' in a row. I knew it was something in orbit, as they all winked out upon hitting the Earth's shadow. I found out just this past year what it was; it turns out there was an Iridium launch around the same time, and I most likely saw the satellite deployment. Wish I'd had a camera." — Dave Dickinson, Spring Hill, Florida

Heck, you can even see flares in broad daylight. Just check the include daytime flares box in the flare listing. Scroll down the list and pick one at magnitude –6 or brighter, triangulate that spot in the sky, then watch and wait.

Other satellite watchers like to use CalSky for their Iridium predictions. After registering (free), you can spend hours exploring the database, checking passes, ground tracks, and sky maps for Iridiums, the ISS, and many other orbiting objects.

"I may have achieved a certain amount of in-group notoriety after spotting flares from all the Iridium satellites that were functional. I annoyed colleagues while observing at Kitt Peak by running out to the dome catwalk to catch them, and even saw one flare during a meeting in Germany while light drizzle was falling." — William C. Keel, professor of physics and astronomy, Univ. of Alabama (Tuscaloosa)

Bob King

Iridium flares make for great photos, so take along a camera with a 35-mm lens (a little shorter or longer focal length is fine, too) and tripod. Once you're set up, click your lens into manual mode and carefully focus on a bright star or the Moon using the Live View function that lets you see the LCD viewfinder in real time. Compose a scene that includes the patch of sky where the satellite will appear. If the sky is dark, set the ISO to 800 and f/stop to 2.8 or 4. About 15 seconds before the flare, open the camera shutter and keep it open until it fades from view for a total time exposure of about 30 seconds.

The transition to the Iridium NEXT generation will be gradual but certain, so make the most of the opportunities that remain. If you're a teacher, do your homework and plan an outing to show a daytime flare to your science class. Anything that gets people talking more about the sky is a good thing, and I guarantee those kids will never forget the sight.

16

16

Comments

Jim

January 27, 2017 at 9:03 pm

I enjoy looking for the flares. I use Heaven's above website. It's neat to see one.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

January 27, 2017 at 11:50 pm

Jim,

I use the same site. Very easy and informative!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob

January 27, 2017 at 11:26 pm

Bob King...

Another great post in your S&T Observing Blog.

Bob King wrote:

"That leaves about 17 months left of razzle-dazzle and an undetermined amount of time as the older units cool their heels in parking orbits until the lights go out."

Bob, can you provide some additional information on the future of the older units?

Thanks.

Bob Patrick

Kentucky

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

January 27, 2017 at 11:49 pm

Bob-Patrick,

Thank you! I tried to get more information from the spokesperson on exactly when the older units would be de-orbited, but he just didn't want to commit to a time. Sounds like they're still trying to schedule them. 2018 sometime?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

S-Breazeal

January 27, 2017 at 11:35 pm

Thanks for that info, Bob, I have to say I'm really sad to hear it! I've taken photos of them and in one case used an Iridium flare to prove to someone that, yes, satellites really do exist. (They thought the ISS and other dim sats were just planes. Seriously.) Next someone will say WWV and WWVH will be taken down.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

January 27, 2017 at 11:51 pm

S.B.,

It's surprisingly what lengths people will go to believe the least likely scenarios!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Howard Ritter

January 28, 2017 at 1:56 am

I'll be sorry to see the last of these brilliant sights. I like to point them out to friends and to the public at observing sessions and tell them they're seeing a small manmade object hundreds of miles away. It's fun to ask people to consider how tiny a patch of sky corresponds to a mirror of, as you say, the size of a door, at that distance, and then to realize how much energy is radiated by the Sun's surface in order for such a tiny patch of it to be so brilliantly visible.

Another observation is that billions of dollars' worth of functional, near-SOTA spacecraft is being discarded if not burned up in order to make way for billions of dollars' worth of a new generation of satellites because the flow of income through the Iridium system is such that doing so is made economically feasible just by the marginal improvement in efficiency and throughput realized. Sobering, and sad, that these magnificent machines are merely commodities, like the "obsolete" personal, scientific, and business computers, tablets, and cell phones that are being junked by the tens of thousands every day...

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

January 28, 2017 at 5:09 pm

Howard,

We do create a lot of trash thanks to the incredible pace of technology.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob

January 28, 2017 at 4:22 pm

Bob King...

I noticed the book Eccentric Orbits: The Iridium Story by reporter John Bloom was published last year by Atlantic Monthly Press. Available at Amazon in various formats. 72 reviews to date.

Bob Patrick

Kentucky

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

January 28, 2017 at 5:14 pm

Thanks Bob-Patrick for sharing the news of this book. I'm headed over for a look 🙂

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Mike

January 28, 2017 at 7:56 pm

thanks for the article, bob.

perhaps the iridium n.e.x.t. replacement generation will have an undiscovered brilliance we will once again enjoy viewing.

in the meantime, i will rely on both calsky and heaven's above for my remaining 18 months of version one flares!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

January 29, 2017 at 12:44 am

Mike,

They may some surprises in store, but I'm told the antennae just wont be up to producing the flares of the previous generation.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Don

January 28, 2017 at 10:42 pm

Thanks for the article. Too bad the next generation can't produce the same sky show! I've always had an interest in astronomy and watched these Satellites for a very long time.

My favorite memory of an Iridium flare was when my grandson was about 3 or 4 years old. I took him outside, told him where and when to look up. The Iridium "performed' on schedule. My g-son looked at me with excitement and said, "Do it again, Papa."

He is now a junior in college, majoring in software engineering. This summer he will be an Intern at the Johnson Space Center, where his grandfather spent his career.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

January 29, 2017 at 12:46 am

Very nice story, Don, and isn't that just like a kid to ask for another of something he or she really liked.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

George-Williams

January 31, 2017 at 2:26 pm

Hey, Bob,

Thanks for including me in the article. I hadn't seen a flare in a while so I checked predictions Friday after I read the story. I saw a -3.6 flare that evening. As a bonus, the ISS was sailing across the southern sky during the flare.

An ill placed cloud prevented me seeing a -8 daytime flare a couple of hours earlier.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

January 31, 2017 at 8:01 pm

George - of course! I really enjoy yours and the other stories.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.