This month's Harvest Moon will be up early to light the night and act as a beacon for watching the annual fall bird migration through a small telescope.

S&T

The Harvest Moon will be here soon. Rising the color of fall-ripened leaves, its light will spill across deserts, forests, oceans, and cities. On successive nights, the Moon will rise only 25–30 minutes later for observers at mid-northern latitudes and even less for northern European and Canadian locations. The short gap of time between successive moonrises gave farmers in the days before electricity extra light to harvest their crops, hence the name.

The Harvest Moon is the full Moon that occurs closest to the autumnal equinox, the beginning of autumn in the Northern Hemisphere. This year the equinox falls on September 22nd at 9:54 p.m. EDT / 6:54 p.m. PDT. Two nights later, at 10:52 p.m. EDT on the 24th, the Moon will be full.

As the Moon orbits the Earth, it moves eastward along the ecliptic, covering a apparent distance of one fist held at arm’s length each night; it rises about 50 minutes later each day. You can follow its orbital travels by comparing the Moon’s nightly position to a bright star or constellation.

Public Domain

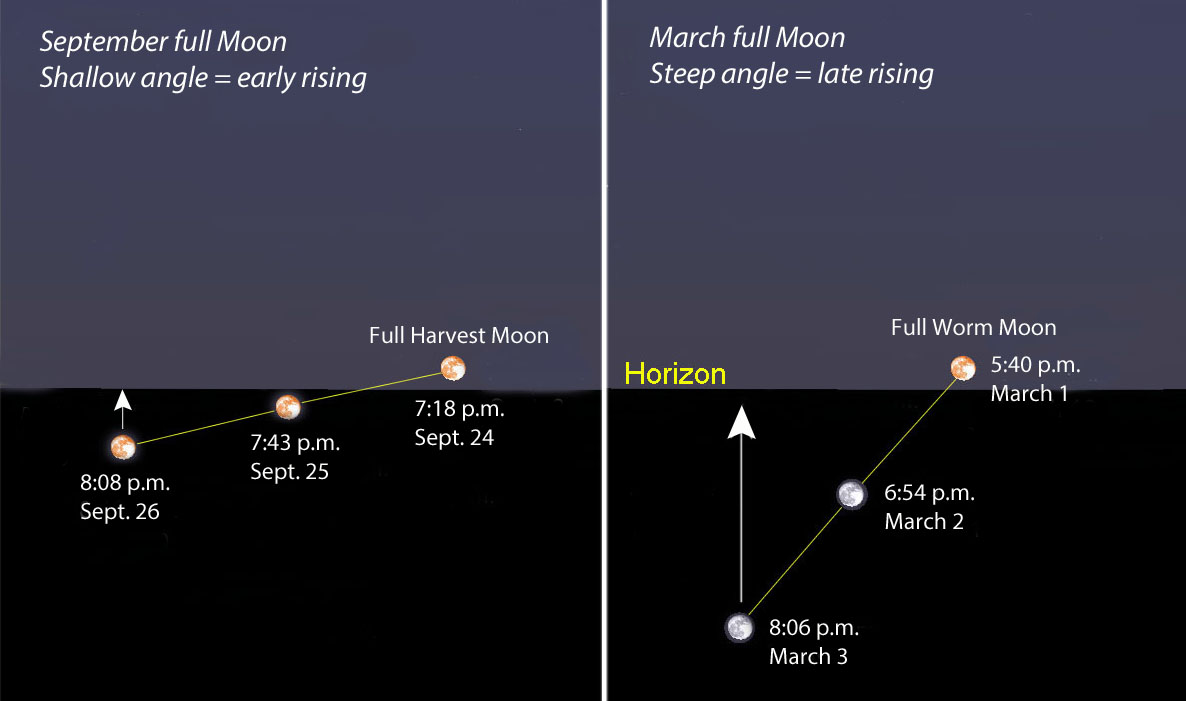

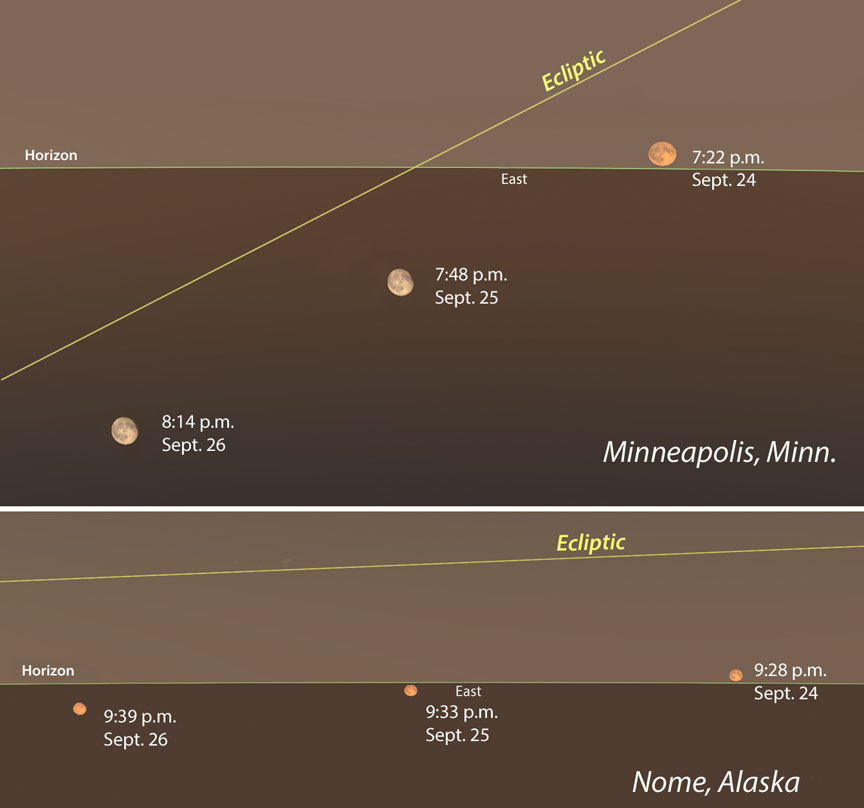

I should say 50 minutes is the usual gap between moonrises. But it can vary from 25 to 75 minutes depending upon the angle the ecliptic makes to the eastern horizon at rise time. In September the ecliptic meets the horizon at a shallow angle around the time of full Moon. As the Moon slides east, it also moves steadily northward this time of year.

Stellarium with additions by the author

The northward motion partly cancels out the eastward motion, keeping the path of September's full Moon shallow with respect to the eastern horizon, with successive rise times separated by 20–30 minutes. Later this month, when the Moon whittles itself to a thin crescent in the morning sky, its path will cut a much steeper angle to the horizon, with rising times separated by up to 75 minutes.

Stellarium with additions by the author

Successive "quick" moonrises at Harvest Moon keeps the bright, gorgeous lunar orb seemingly pinned to the twilight sky for several nights in a row. The Harvest Moon effect becomes more noticeable the further north you live, as its rising path is more nearly parallel to the horizon. From Aberdeen, Scotland (latitude 57° N) only 16 minutes separate successive moonrises from September 23rd through the 27th. For skywatchers in Nome, Alaska (64.5° N) that dwindles to just 5–7 minutes during the same interval, while in Barrow (71°N) the Moon has the audacity to rise 10–11 minutes earlier each night. Since fall is whaling season there, the extra light may still serve its ancient purpose.

I love a full Moon rising in the east at sunset. It's something to be enjoyed with the naked eye for its ever-changing colors and weird distortions introduced by atmospheric refraction and dispersion. Once the Moon has ascended a bit, I'd like to suggest a different way to observe it appropriate for the fall season — birdwatching. Like actors in a play against a white shadow screen, birds flutter in inky silhouette across the glaring lunar limelight, zipping over Copernicus and Tycho as they wing south for the winter.

Bob King

Many birds migrate at night, both to conserve energy and avoid predators. Identifying specific warblers, sparrows, vireos, orioles, and other species that fly across the moon may be next to impossible, but seeing them is easy and expert birders can make rough classifications.

Every fall, I use the full Moon to go bird hunting, taking time to see what flies by. I count birds in 5- or 10-minute intervals and multiply to arrive at an approximate hourly rate. Last fall, I counted bird silhouettes in the 5-minute interval between 10:57 and 11:02 p.m. one night. The total came to 16, which multiplied by 12 yielded an hourly count of 192 birds.

Most nighttime migrators begin their flight right after sunset and continue until about 2 a.m. Peak time is between 11 p.m. and and 1 a.m. Birds typically migrate at altitudes ranging from 1,500 to 5,000 feet, but on some nights, altitudes may range from 6,000 and 9,000 feet. I could tell the high ones from the low ones by their size and sharpness. Nearby birds flew by out of focus, while distant ones were very sharply defined and took longer to cross the moon.

Using data from 143 weather stations across North America, experts at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology counted an average of 4 billion birds heading south out of Canada to the U.S. in the fall and 4.7 billion leaving the U.S. for Mexico and points south. You can learn more about the study here.

Watching birds pass across the moon is a pleasant activity reminiscent of meteor shower watching. At first you see nothing, then suddenly a bird flies by. A minute later, two might wing by in tandem. Both activities keep us on our toes in anticipation of what the next moment might hold.

Bob King

The best time to watch the nighttime avian exodus is around full Moon, when the big, round disk offers an ideal spotlight on the birds’ behavior. It’s a fine sight to see one of Earth’s creatures streak across an alien landscape, and another instance of how a distant celestial body "illuminates" earthly activities in a unique way.

13

13

Comments

Bob

September 20, 2018 at 2:27 am

Bob King...

I really like this article about the Harvest Moon that will take place in a couple of nights. Too often, the full moon receives a bad rap from amateur astronomers for affecting deep space observing. But every time I take the opportunity to observe a full moon--I get goose bumps.

Thanks for the article.

Bob Patrick

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

September 20, 2018 at 1:57 pm

Thanks Bob. I'm a big Moon-lover, too 🙂

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Rod

September 20, 2018 at 10:07 am

Bob, good report. "As the Moon orbits the Earth, it moves eastward along the ecliptic..." This year, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn moved retrograde near the ecliptic and now they are moving eastward again (see positions 09-Mar thru 06-Sep and today). The Moon does not move retrograde in the night sky and then begin eastward movement again. The Moon orbits the Earth, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn do not 🙂 Easy observational evidence for the heliocentric solar system that accurately predicts this motion change.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

September 20, 2018 at 1:57 pm

Rod,

I love that! I never thought about the lack of lunar retrograde motion as proof of the heliocentric theory. Wonderful.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Rod

September 20, 2018 at 2:43 pm

Thanks Bob. Since I retired in early January 2016, I periodically interact with flat earth teachers - all geocentric. I never heard of the flat earth movement until I retired :). I find simple, observational astronomy is very useful, especially telescope views I document showing position changes of the planets near the ecliptic, brightness, and angular size changes over the months. Great fun, and consternation for some 🙂

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

September 20, 2018 at 3:25 pm

Rod,

Sometimes seeing can really be believing.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Anthony Barreiro

September 20, 2018 at 4:52 pm

I'm looking forward to this year's unequivocal harvest Moon. In some years there's a full Moon a couple of weeks before the equinox and another a couple of weeks after. That makes the designation of harvest Moon somewhat arbitrary. But this year, there's no doubt! Hopefully we'll have clear weather. I'll be up on Bernal Hill with binoculars mounted on a tripod to share the view with my fellow lunatics. Watching the harvest Moon rise over the east bay hills and San Francisco Bay has become an informal holiday for the community living around Bernal Hill.

I love the idea of using the full Moon to do a migratory bird count. Cornell ornithology has created "birdcast" using weather radar not just to count migrating birds, but to predict nightly migration numbers by integrating the current weather forecast and past data. Birders have started using birdcast like amateur astronomers use clear sky chart, to decide when to stay up late or get up early. And also rather like amateur astronomers, migrating birds themselves tend to lay low in the bad weather before and during a rainstorm and to take advantage of the clear skies behind the frontal system.

There is some hope that the birdcast might be used to convince the people responsible for severe light pollution, such as animated billboards, highrises, oil and gas wells, etc. to turn down the lights on nights when there will be particularly high numbers of birds migrating. If so, this would be a good thing. Millions of birds die each night because they become disoriented and exhausted, or fly full speed into brightly lit buildings.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Anthony Barreiro

September 20, 2018 at 4:53 pm

Here's the website for the birdcast: http://birdcast.info/

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

September 21, 2018 at 3:36 pm

Hi Anthony,

The link you provided was most useful. Thank you! I hope others click on it to get the bird migration forecast.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Anthony Barreiro

September 22, 2018 at 5:40 pm

I'm glad you find it useful!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Herb Hess

September 15, 2019 at 9:11 am

Nice article. You give a really helpful and easily understood explanation.

For what it's worth, the same phenomenon occurs in the Southern Hemisphere, but in March, not in September, and for the same reasons.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

September 15, 2019 at 11:46 am

Thank you, Herb! My pleasure. I wonder if it's as much of "a thing" in the southern hemisphere. That would be the time of the harvest in days past, so I'm guessing

it played an important role there, too.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Herb Hess

September 16, 2019 at 5:58 pm

The numbers are the same for the same latitudes, north or south. In other words, in Chile and Argentina, at 40 degrees South latitude, the behavior is the same at it is in the USA or Asia at 40 degrees North latitude. That's easy to check with moonrise tables on the Internet.

Variations are within any error caused by the five degrees of tilt in the moon's orbit.

Why may we not have heard of it? There is far less population and far less land mass used for agriculture in the southern temperate zone than there is in the northern hemisphere, particularly at higher latitudes where the effect is more pronounced and noticeable. Over many centuries, the effect developed a strong cultural component, as is the case for many astronomical phenomena. Earth's dominant cultures originated in the north temperature zone and still dominate from there, so they get most of the press. We do know that southern hemisphere cultures have their own constellations, legends, and customs based on a different set of stars and perspectives. For example, ask any Australian about the "man in the moon" and you'll get a different description entirely because the moon there appears "upside down" from how it appears in North America and their culture describes it differently.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.