Some daily events in the changing sky for December 18 – 26.

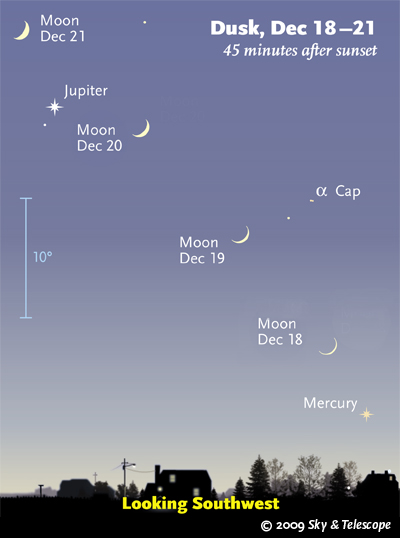

The waxing crescent Moon points the way to Mercury low in the cold twilight. The 10° scale as about the size of your fist held at arm's length. (These scenes are drawn for the middle of North America. European skywatchers: move each Moon symbol a quarter of the way toward the one for the precious date.)

Alan MacRobert

Friday, December 18

Saturday, December 19

Sunday, December 20

After dark on Sunday and Monday, the Moon poses by bright Jupiter and faint Neptune, which is invisible to the naked eye.

Sky & Telescope diagram

Monday, December 21

Tuesday, December 22

Wednesday, December 23

Orion's Belt points the way down to rising Sirius. Betelgeuse, Sirius, and Procyon form the nearly equilateral Winter Triangle.

Sky & Telescope diagram

Thursday, December 24

Friday, December 25

Carefully note the sunset point on your horizon from day to day. Can you see that it's already beginning to creep a little north?

Saturday, December 26

Want to become a better amateur astronomer? Learn your way around the constellations. They're the key to locating everything fainter and deeper to hunt with binoculars or a telescope. For an easy-to-use constellation guide covering the whole evening sky, use the big monthly map in the center of each issue of Sky & Telescope, the essential magazine of astronomy. Or download our free Getting Started in Astronomy booklet (which only has bimonthly maps).

Sky Atlas 2000.0 (the color Deluxe Edition is shown here) plots 81,312 stars to magnitude 8.5. That includes most of the stars that you can see in a good finderscope, and typically one or two stars that will fall within a 50× telescope's field of view wherever you point. About 2,700 deep-sky objects to hunt are plotted among the stars.

Alan MacRobert

Once you get a telescope, to put it to good use you'll need a detailed, large-scale sky atlas (set of charts; the standards are Sky Atlas 2000.0 or the smaller Pocket Sky Atlas) and good deep-sky guidebooks (such as Sky Atlas 2000.0 Companion by Strong and Sinnott, the more detailed and descriptive Night Sky Observer's Guide by Kepple and Sanner, or the classic Burnham's Celestial Handbook). Read how to use them effectively.

Can a computerized telescope take their place? I don't think so — not for beginners, anyway (and especially not on mounts that are less than top-quality mechanically). As Terence Dickinson and Alan Dyer say in their Backyard Astronomer's Guide, "A full appreciation of the universe cannot come without developing the skills to find things in the sky and understanding how the sky works. This knowledge comes only by spending time under the stars with star maps in hand and a curious mind." Without these, "the sky never becomes a friendly place."

More beginners' tips: "How to Start Right in Astronomy".

This Week's Planet Roundup

Jupiter continues to shrink as it moves westward toward conjunction; turn a telescope on it in late twilight while it's still at its highest. The North Equatorial Belt remains massively broad and dark, while the South Equatorial Belt has greatly faded and is divided into two narrow parts. Christopher Go in the Philippines took this image on December 14th at 10:17 UT, when System II longitude 281° was on the planet's central meridian. South is up.

Stacked-video images like this can show much more detail on a planet than the same telescope will reveal to the human eye.

Christopher Go

Mercury (magnitude –0.5 fading to +0.5) is visible low in the southwest in twilight. Look about an hour after sunset. Mercury remains near elongation all week but loses brightness quite noticeably during this time.

Venus is lost in the sunrise. Not until late winter (Northern Hemisphere winter) will it emerge into view again, after sunset.

Mars (magnitude –0.5, in Leo) rises around 8 p.m. local time, far below Castor and Pollux a bit north of east. A little later, twinkly Regulus rises about a fist-width beneath it. Mars and Regulus are very high in the south in the hours before dawn, now lined up horizontally.

In a telescope, Mars is 11.5 to 12 arcseconds wide and growing. The north polar cap is in good view, bordered by a wide dark collar. Do you see other surface features? Identify them with the Mars map and observing guide in the December Sky & Telescope, page 57. Mars is on its way to opposition in late January, when it will reach 14.1 arcseconds wide.

Jupiter and Neptune had a previous conjunction last July. On the morning of July 9th, Bob Kimmel of Rockledge, Florida, took this image. Why are they so different in brightness? Jupiter is a bigger planet, but the main reasons are that Jupiter is closer to the Sun (so it gets illuminated more brightly) and also closer to Earth.

Kimmel used an 8-inch f/5 Newtonian reflector with a Canon D20a DSLR camera body on his back patio. This is an unguided 20-second exposure at ISO 3200.

Bob Kimmel

Jupiter (magnitude –2.2, in Capricornus) shines brightly in the south-southwest in twilight, and lower in the southwest after dark. It sets by 8 or 9 p.m. Jupiter is moving lower west toward the sunset week by week, sets earlier, and continues to shrink as Earth pulls farther away from it in our faster orbit. In a telescope Jupiter is currently 36 arcseconds wide, compared to 49″ around its time of opposition last August.

Saturn (magnitude +1.0, in the head of Virgo) rises in the east around midnight and shines highest in the south before and during dawn. Its rings are still narrow, tilted 4.8° from edge-on to us.

Uranus (magnitude 5.8, just below the Circlet of Pisces) is highest in the south right after dark.

Neptune (magnitude 7.9, in Capricornus) lurks closely in the background of Jupiter, which shines 10,000 times brighter. Nevertheless Neptune is detectable in good binoculars. Jupiter and Neptune reach conjunction, with Neptune 0.6° north of Jupiter, on the evening of December 19th. By the 25th they widen to 1.0° apart. To identify Neptune (and Uranus) among other faint points, use our finder charts for these two planets.

Pluto is in conjunction, behind the glare of the Sun.

All descriptions that relate to your horizon or zenith — including the words up, down, right, and left — are written for the world's mid-northern latitudes. Descriptions that also depend on longitude (mainly Moon positions) are for North America. Eastern Standard Time (EST) equals Universal Time (also known as UT, UTC, or GMT) minus 5 hours.

To be sure to get the current Sky at a Glance, bookmark this URL:

http://SkyandTelescope.com/observing/ataglance?1=1

If pictures fail to load, refresh the page. If they still fail to load, change the 1 at the end of the URL to any other character and try again.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.