Some daily events in the changing sky for December 4 – 12.

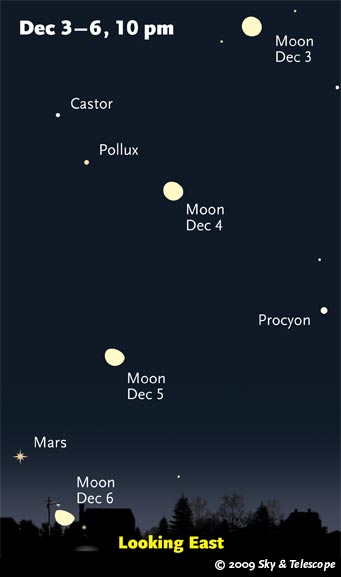

As the Moon wanes away from full, watch it descend the late-evening sky on its way to meeting Mars. (This scene is drawn for the middle of North America. European observers: move each Moon symbol a quarter of the way toward the one for the previous date.)

Sky & Telescope diagram

Friday, December 4

Saturday, December 5

Sunday, December 6

Monday, December 7

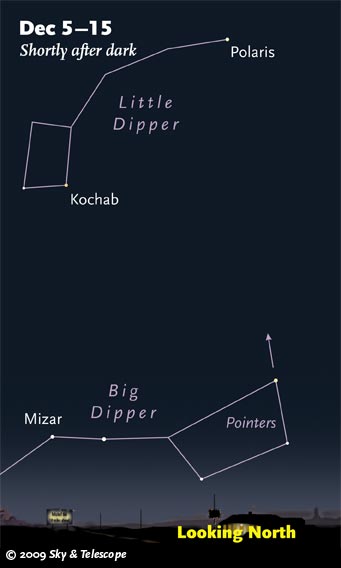

This is the time of the year when the Little Dipper dumps into the Big Dipper right after dark. This is the view from latitude 40° north (for example New York and Denver). In the southern U.S., part of all of the Big Dipper is below the horizon.

Sky & Telescope

Tuesday, December 8

Wednesday, December 9

Thursday, December 10

Friday, December 11

Saturday, December 12

Last August, Epsilon Aurigae was still as bright as Eta Aurigae. Since then it has been dimming into its predicted 2-year partial eclipse, something that happens every 27 years. It should be reaching minimum light about now. The difference between Epsilon and Eta is pretty plain now if you look carefully. See our article on this mysterious star in the May Sky & Telescope, page 58.

Sky & Telescope diagram

Want to become a better amateur astronomer? Learn your way around the constellations. They're the key to locating everything fainter and deeper to hunt with binoculars or a telescope. For an easy-to-use constellation guide covering the whole evening sky, use the big monthly map in the center of each issue of Sky & Telescope, the essential magazine of astronomy. Or download our free Getting Started in Astronomy booklet (which only has bimonthly maps).

The Pocket Sky Atlas plots 30,796 stars to magnitude 7.6 — which may sound like a lot, but that's less than one star in an entire telescopic field of view, on average. By comparison, Sky Atlas 2000.0 plots 81,312 stars to magnitude 8.5, typically one or two stars per telescopic field. Both atlases include many hundreds of deep-sky targets — galaxies, star clusters, and nebulae — to hunt among the stars.

Sky & Telescope

Once you get a telescope, to put it to good use you'll need a detailed, large-scale sky atlas (set of charts; the standards are Sky Atlas 2000.0 or the smaller Pocket Sky Atlas) and good deep-sky guidebooks (such as Sky Atlas 2000.0 Companion by Strong and Sinnott, the more detailed and descriptive Night Sky Observer's Guide by Kepple and Sanner, or the classic Burnham's Celestial Handbook). Read how to use them effectively.

Can a computerized telescope take their place? I don't think so — not for beginners, anyway (and especially not on mounts that are less than top-quality mechanically). As Terence Dickinson and Alan Dyer say in their Backyard Astronomer's Guide, "A full appreciation of the universe cannot come without developing the skills to find things in the sky and understanding how the sky works. This knowledge comes only by spending time under the stars with star maps in hand and a curious mind." Without these, "the sky never becomes a friendly place."

More beginners' tips: "How to Start Right in Astronomy".

This Week's Planet Roundup

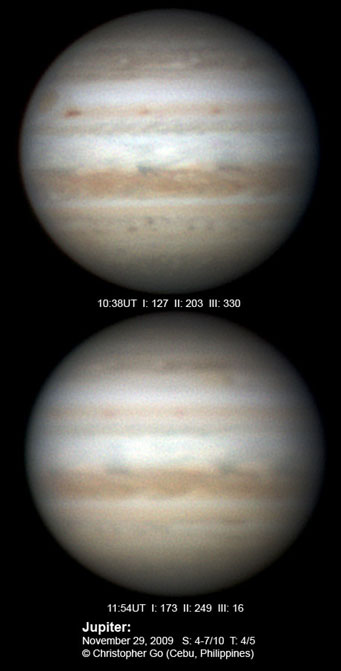

Jupiter is getting smaller week by week as Earth pulls farther ahead of it in our orbit around the Sun. These images were taken by Christopher Go on November 29th. In the top image, the Great Red Spot is just about to rotate off the preceding (celestial western) limb. By the time of Go's second image, 1 hour 16 minutes later, Jupiter was lower in the sky and the seeing was much worse.

Note the four small, dark red spots following the Great Red Spot at nearly the same latitude. (The fourth is seen best in the bottom image, after Jupiter had rotated substantially.)

South is up. The South Equatorial Belt has faded greatly compared to the darker North Equatorial Belt. And its north and south components are now different colors!

Stacked-video images like these usually show much more detail than a planet will show to the eye through the same telescope.

Mercury (magnitude –0.5) is low in the sunset but getting a little higher every day. About 30 minutes after sundown, use binoculars to scan for it just above the horizon due southwest. On what day will you first see it with your unaided eyes?

Venus (magnitude –3.9) is lost deep in the sunrise. Not until late this winter (Northern Hemisphere winter) will it emerge into view again in the sunset.

Mars (magnitude –0.2, at the Cancer-Leo border) rises around 9 or 10 p.m. local time, far below Castor and Pollux a bit north of east. A little later, twinkly Regulus rises a fist-width beneath it. Mars and Regulus are very high in the south in the hours before dawn.

In a telescope, Mars is 10.4 arcseconds wide and growing. The planet's north polar cap is in good view this season, bordered by a wide, dark collar. Any other surface features? Clouds? See the Mars map and observing guide in the December Sky & Telescope, page 57. Mars is on its way to opposition in late January, when it will be 14.1 arcseconds wide.

Jupiter (magnitude –2.2, in Capricornus) shines brightly in the south-southwest in twilight, and lower in the southwest later. It sets by 10 p.m. local time.

Saturn (magnitude +1.0, in the head of Virgo) rises around 1 a.m. and shines high in the southeast before and during dawn. Its rings are still narrow, tilted only 4° from edge-on.

Uranus (magnitude 5.8, below the Circlet of Pisces) is highest in the south during early evening.

Neptune (magnitude 7.9, in Capricornus) lurks closely in the background of Jupiter, which shines 11,000 times brighter. Nevertheless Neptune is detectable in good binoculars. Jupiter and Neptune are 2½° apart on December 4th and 1½° apart on the 11th. To identify Neptune (and Uranus) you'll need to use our finder charts for these two faint planets.

Pluto is behind the glare of the Sun.

All descriptions that relate to your horizon or zenith — including the words up, down, right, and left — are written for the world's mid-northern latitudes. Descriptions that also depend on longitude (mainly Moon positions) are for North America. Eastern Standard Time (EST) equals Universal Time (also known as UT, UTC, or GMT) minus 5 hours.

To be sure to get the current Sky at a Glance, bookmark this URL:

http://SkyandTelescope.com/observing/ataglance?1=1

If pictures fail to load, refresh the page. If they still fail to load, change the 1 at the end of the URL to any other character and try again.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.