Fifty years ago today was the launch of Apollo 8: the first manned mission to (and around) the Moon. In England — far from the launch but not the excitement — a young man glimpsed the rocket on its way.

One Fine Evening

The evening of December 21, 1968, was fine where my parents and I were then living: the county town of Chelmsford, about 35 miles north-east of London. Even in England there had been huge excitement about the launch that afternoon of the first manned mission to the Moon-mission, our newspapers and television having been full of the story for days previously. The all-encompassing nature of that excitement left practically no corner of society untouched and unmoved. This certainly wasn’t just the biassed view of a star-struck 16-year-old, as I was in those days.

Christopher Taylor

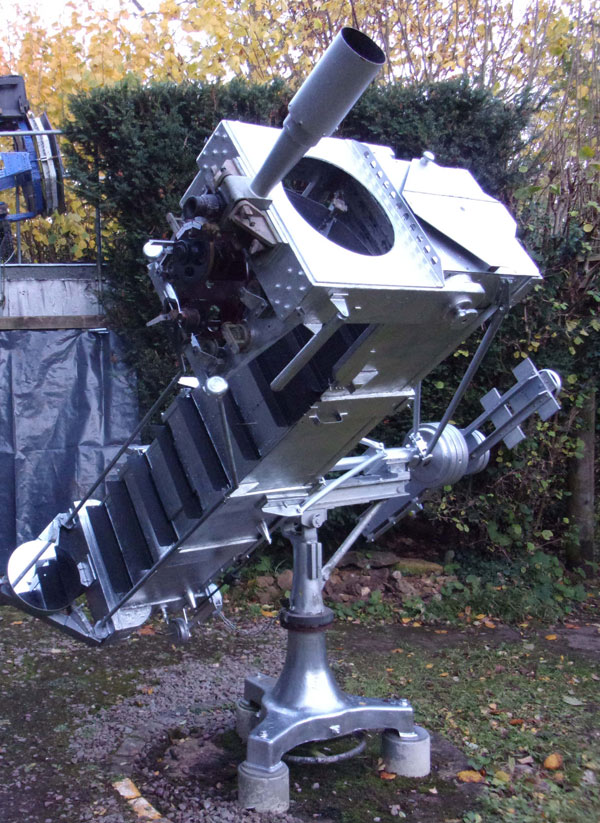

The routine of our little household was rarely disturbed, however, by the events and “sensations” of the outside world. That evening my late father and I were out peaceably in the garden some time after nightfall, observing with the 12.5-inch Newtonian reflector which I had been given by its previous owner, Mr. R. McIver Paton F.R.A.S., just over a year earlier. That veteran instrument is still in regular use to this day.

On the evening in question, we were out at the telescope shortly after 6 p.m. (GMT) and had been looking for some time at Saturn, which I was keen to show Dad as it was then well placed in the south. While he was up at the eyepiece some seven feet off the ground, I steadied the step-ladder on which he was standing and passed the time by gazing about at the rather beautiful sky; a crescent Moon of cat’s-whisker thinness had just set and Venus was playing the Evening Star low in the west.

Suddenly, my attention was drawn by a first-magnitude star in that direction. For a few moments I took it for Vega, until it dawned on me that that had passed behind a large tree on that horizon and that, in any case, this object was noticeably fuzzy despite a cloudless sky of mountain clarity. (Those conditions do happen in England occasionally!). “Dad, there’s something strange over there in the west which I think we should take a look at” I said.

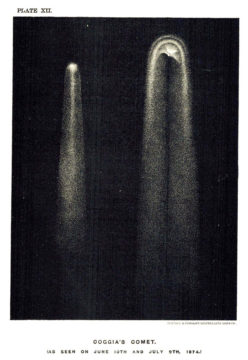

On swinging the ponderous, half-ton mass of the 12½-inch scope in that direction and remounting the steps, a glance through the telescope’s 11x80 finder instantly disposed of any notion that this was a mere star. The first view through the main optics was jaw-dropping: a vast, nebulous mass with a sharply defined, elegantly parabolic outline, nearly filled the 1-degree field of the x75 “sweeping power.” Just within its sunward envelope, the cloud was scooped out in two black hollows, symmetrically placed either side of the centerline. Their adjacent forward edges met in an acute cusp on that centerline, where there was a tiny spark of light resembling a 10th-magnitude star. In short, it looked just like the head of a great comet, an appearance which — inexperienced observer though I was in those days — was already familiar from the picture of Coggia’s Comet 1874 in my copy of Sir Robert Ball’s Story of the Heavens.

At that point, just as we were admiring this unexpected celestial spectacle, my mother came rushing out from the house to say that our close family friend Robert Ash was on the telephone, having himself just been phoned by his chum Henry Wildey, who was in a great state of excitement about “the new comet.” Henry was a famous figure of British amateur astronomy in the sixties, being Curator of Instruments of the British Astronomical Association and a well-known commercial maker of rather good refractor objectives. (I have one of his 5-inch glasses, which is about to take on a new role as guide-scope on the 12½-inch.)

Despite all of this, I wasn’t convinced that the new object in the western sky was a comet. No such object had been in the sky the previous night, and it was at a considerable altitude, well clear of the horizon, so certainly no sun-grazing comet. Its sudden appearance and the perfect coincidence in date with the much-publicized Apollo 8 launch both seemed to lie uncomfortably with that suggestion. Surely this must be something to do with the American moonshot?

In truth, I had no idea at that moment whether any aspect of the mission could explain what we were seeing, or, even if so, whether it would be visible from the UK. Certainly, no advance notice of any such possibility had come my way.

How Apollo 8 Made a “Comet”

In fact it was precisely Apollo 8, or rather the booster that had sent it heavenward, that I had seen. The Saturn V rocket carrying the mission had lifted off at 12:51 UT (GMT). About 2½ hours later, a burn of the S-IVB booster had flung the spacecraft out of Earth-orbit onto its Moon-looping trajectory. Some 2½ hours after that, that is just before 6 p.m. local time, the booster separated from the Apollo mooncraft. Once it flew free, the astronauts gave the command to dump all the spare liquid oxygen from the tanks of the now-redundant booster. That large release of volatile oxygen into the vacuum of space must have blown up rapidly into a huge rarefied gas cloud. Moving in roughly the same direction as the Apollo command module, this cloud was bathed in the Sun’s ultraviolet radiation and solar wind. The obvious result: an artificial comet-head! The 10th-magnitude “star” at the center of the cloud was presumably sunlight glinting off the hull of the spaceship or the S-IVB booster. All of the observed phenomena fit perfectly with this explanation of what I saw that night.

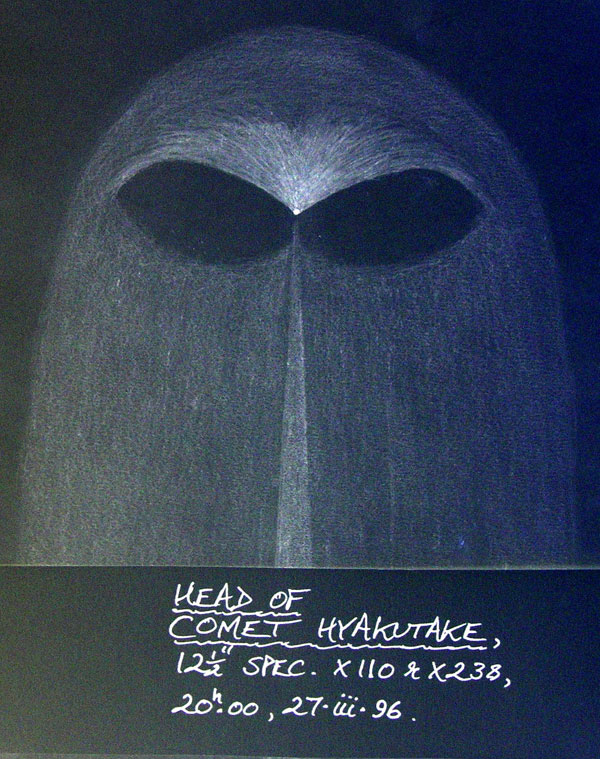

Although the “hairy star” of December 21, 1968, was not a comet, nonetheless the head of one of these great celestial visitors provided by far the best representation of what I saw that evening. I observed most of the brighter comets in the succeeding decades, but it was to be nearly 30 years before I again witnessed the same sort of sight in the 12½-inch: Comet Hyakutake was the best mimic I have yet seen of Apollo 8 on that memorable night.

Christopher Taylor

This sketch of Hyakutake provides the best impression I can give of the visual appearance of Apollo 8 in the same telescope. In fact, my immediate thought on putting eye to eyepiece so many years later was their striking similarity. Granted, the inner and outer parabolae not quite so beautifully defined as in 1968, and the central “cusp” was a little blunter but in all other respects it was the moonshot “to the life.”

Reports of the Apollo 8 Phenomenon

In hindsight it’s rather curious that such a conspicuous apparition in an early-evening, brilliantly clear sky observed by a significant number of sky-watchers over a large part of England, if not further afield, was not more widely reported at the time. And it has left little trace in what has been written since. I note, for instance, that the long Wikipedia article on Apollo 8 makes no mention whatever of any ground-based sightings of the spacecraft or attendant phenomena while in transit.

No doubt this is partly explained by there having been broad daylight over the whole of the continental United States at the time of the S-IVB oxygen dump, so there would have been no chance of anyone there seeing the spectacular sky-display that resulted. It is more surprising that even in the UK very little was made of this after the event, even though a number of experienced observers had certainly seen it.

At the January 1, 1969, meeting of the British Astronomical Association, several leading members discussed their observations of the phenomenon, which were briefly reported in the February issue of the association’s Journal (J.B.A.A. 79, 93, 1969). From that report, it appears that photographs were successfully taken by at least three observers, including several from Sevenoaks in Kent by the well-known Commander Henry Hatfield R.N. (1921-2010), but I have never seen any of these images published.

There was to be at least one other occasion when such a propellant dump display was visible from the British Isles, and that was from Apollo 12 on the night of November 14, 1969. That time, I caught only a brief naked-eye glimpse of the big, fuzzy ball of light, again of about first magnitude, through a rent in flying clouds. Others were more fortunate, however, despite a sky far less favorable than the previous December. The Journal of the British Astronomical Association carried an interesting and fairly detailed report (J.B.A.A. 80, 230-232, 1970) of visual observations by 11 association members from Kent to Northern Ireland, including one Qantas airline pilot and his crew while in flight.

All of this happened a very long time ago now, but that December night of 1968 provided me with one of the most memorable experiences of my observing life, one that still lives keenly in my mind’s eye and conjures up powerful emotions. Not least of those emotions is huge admiration for those brave men who flew in Apollo 8, knowing full well the significant personal risks they were taking, and for the legions of brilliant scientists, engineers, and skilled machine-shop workers whose dedication made that great adventure possible: We salute you.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.