In a spectacular case of bad timing, the full Moon coincides with the annual Geminid meteor shower. Don't feel put out. There's still something for everyone, including a consolation prize.

Sky & Telescope

A supermoon is a good thing. So is a rich meteor shower. But the two together? Maybe not so good. But that's exactly what will happen on the night of December 13–14 when the Moon reaches full phase at 7:06 p.m. Eastern time just hours before the peak of the annual Geminid meteor shower.

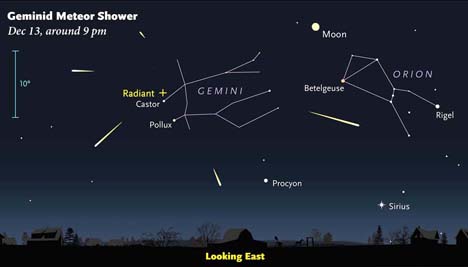

The brilliant Cold Moon, the third of this year's three supermoons, will flood the sky with light all night long and slash the number of Geminids visible from around 120 per hour to more like a dozen per hour. Shower members, which can appear anywhere in the sky, all trace their paths back to a radiant point near the star Castor in Gemini, the constellation that lends its name to the famous downpour.

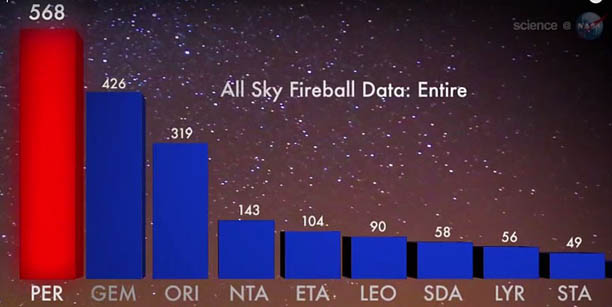

Is a dozen an hour worth it? You bet. The Geminids are one of the most consistent and richest showers of the year. Fireballs are common. It's also one of the few showers that's active during mid-evening because the radiant is already well up in the eastern sky by 10–10:30 p.m. local time. If you don't want to set the alarm for a chilly 2–4:00 a.m. session, when Gemini reaches its greatest altitude in the southern sky, you can get a passably good look at the shower before bedtime.

Ranbo55

Invite a friend over or take your kids out for a look. Just make sure everyone's dressed warmly and preferably stretched out on lounge chairs under sleeping bags or warm blankets. Or fire up the hot tub, a favorite hangout for shower watching. Face east or north before midnight and try to avoid looking at the Moon to preserve whatever night vision you can muster.

NASA

After midnight and before dawn, face south or west. Geminids are one of the few showers that don't originate from dust strewn by a comet. Instead, the stream's parent body is the asteroid 3200 Phaethon (FAY-eh-thon). Sometimes referred to as a "rock comet," Phaethon is a rare asteroidal object that primarily ejects fragments of rock instead of water vapor, gases and dust when heated by the Sun the way comets do.

Trails of dust have occasionally been observed departing Phaethon, seeding its orbit with future Geminids. Each year in mid-December, the Earth passes through the debris, which smacks into the atmosphere at 80,000 miles per hour (129,000 km/hr). Each entering particle's great speed briefly sets the air aglow to create a titillating meteor flash. Because asteroidal material can penetrate the atmosphere more deeply than comet dust, Geminids produce longer streaks than some showers.

Bob King

Of course it will be hard to ignore the Moon that night. And you shouldn't. If we define a supermoon as a full Moon that occurs within 90% of its closest distance to Earth, December's Moon makes the cut, even if it's the most distant of the year's supermoon trio. Second place goes to the October Hunter's Moon and first to the Beaver Moon on November 14, the closest supermoon since 1948.

The December Moon will glare from eastern Taurus near the Gemini border and climb even higher in the sky than last month's, beaming down with enough intensity to render some aspects of the landscape in color, such as signage, trees, and even bright clothing.

Occult 4.2

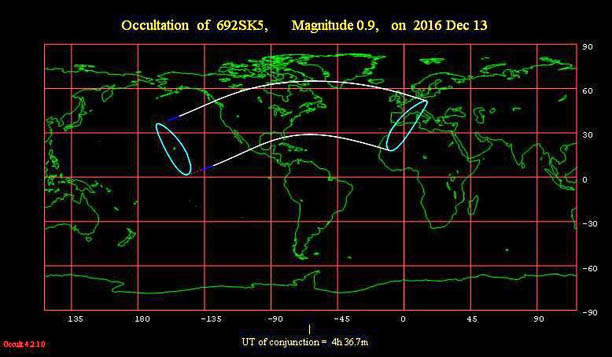

If you're still feeling a sense of disappointment at seeing the Geminids pared back, there's a consolation prize. The night before the great clash, the waxing Moon will hit the bullseye — literally — when it occults the star Aldebaran in Taurus. On the evening of December 12th across the Americas (early morning of the 13th for Western Europe), you can use binoculars or a telescope to watch the Moon cover and then uncover the bright star.

Stellarium (left) / Gianluca Masi

An example is shown above; click here for times for more than 1,100 U.S., Canadian, and European cities. Because the listed times are in UT, remember to subtract 5 hours to convert to Eastern Standard, 6 for Central, 7 for Mountain, and 8 for Pacific.

My location has been under clouds for so many nights, I can't wait to see any or all of these wonderful events. Moonlight, meteors, and a disappearing star — sounds positively festive!

11

11

Comments

December 9, 2016 at 4:35 pm

Shouldn't the conversion from UTC to ET be -5 hours? And correspondingly one hour more in the other time zones (i.e. anywhere no longer in daylight savings time)

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Paul-Cox

December 9, 2016 at 8:03 pm

Yes - current UTC is 5hrs ahead of eastern time.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

December 9, 2016 at 10:09 pm

Hi Paul and skater,

My brain was stuck in Daylight Saving mode - thanks! Now corrected back to standard time.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Cousin Ricky

December 10, 2016 at 11:50 pm

What are the coordinates of the radiant? Patrick Moore's Data Book of Astronomy says 07h 28m +32°, but your illustration shows a point close to 07h 07m +33°. Looking around the Web, universetoday.com says 07h 48m +32°. Is there some authoritative source that can clear up these discrepancies?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

December 11, 2016 at 12:57 am

Cousin Ricky,

This is an excellent observation and question. Many sources list 7h 28m or 7h 30m (with declination varying from +32° to +33°), but the International Meteor Organization and American Meteor Society both list the radiant at R.A. 7h 33m, Dec. +32° for the shower peak. These are also the figures reported by meteor researcher Peter Jenniskens in his exhaustive work "Meteor Showers and their Parent Comets."

You can safely rely on those as definitive. Having said that, the Sky and Telescope chart shows the radiant at about 7h 08m, which indeed is incorrect -- for the shower peak! You'll also see it shown at the same location in this 2015 AMS article/map (http://www.amsmeteors.org/2015/12/viewing-the-geminid-meteor-shower/).

Given its source, I naturally assumed the map was accurate, but I see now that other S&T maps place the radiant much closer to Castor, the correct position. Here's my hunch about the origin of the discrepancy. The Geminid radiant drifts eastward about 1° per day, so the position shown on the S&T chart corresponds to the radiant's location on Dec. 10 when the shower first becomes noticeably active.

To ensure accuracy, I shifted the radiant on the chart in the article to the correct position for shower peak. Thank you for writing!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Cousin Ricky

December 12, 2016 at 11:03 am

Thanks for the prompt response!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

December 12, 2016 at 11:48 pm

You're welcome!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

December 11, 2016 at 1:57 am

Hi, Bob:

I recently discovered a new idea for taking pictures with a full Moon in the Sky. On Nov 18th, the GEOS 15 min satellite projection had shown me that driving to southeastern Illinois would be the best way to give me a chance of getting out from under the cloudy skies in upper Illinois. I had been to Walnut Point State Park in 2008, and found the abandoned Univ IL observatory on the west side of the park. I stopped there on 11-18-2016, and found there was about 30 % cloud cover, so I stayed. I usually use the walls of dry quarries to reduce the city sky glow in northern IL. Here, at Walnut Point, I noticed a strong Moon shadow close to the tall Pine trees and set up my cameras within that shadow. It may not be a good solution to blocking the Moon's effect, but it made me feel better. 🙂 I have downloaded a pic taken under those circumstances. j I ran two cameras, and only saw one Leonid meteor, which my cameras did not catch, during two hours of observation.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

December 11, 2016 at 11:07 am

OrinK3,

Anything that makes you happier taking photos is a good thing. But seriously, yes, setting up in a shadow not only preserves your night vision a bit since there's no chance of looking at the Moon, but also avoids potential glare in the camera lens. I do something similar when photographing a meteor shower in bright moonlight -- pointing the camera to the opposite side of the sky from the moon.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Paul-Cox

December 11, 2016 at 10:25 am

I created this time-lapse together of rocky comet/asteroid "3200 Phaethon" last night using Slooh's 17" Canary Islands telescope. We had some light cloud to contend with. Currently mag 18.

https://twitter.com/AstroPRC/status/807946442706944000

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

December 11, 2016 at 11:15 am

That's wonderful, Paul. Thank you very much for sharing the animation. I think readers will enjoy seeing it, knowing that 3200 Phaethon is up there at the same time they're watching the Geminids!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.