Friday, Oct. 11

• Soon after dark, you'll find zero-magnitude Arcturus low in the west-northwest at the same height as zero-magnitude Capella shining in the northeast.

When this happens, turn to the south-southeast, and there will be 1st-magnitude Fomalhaut at the same height — if you're at latitude 43° north. Seen from south of that latitude Fomalhaut will appear higher; from north of there it will be lower.

Now turn southwest. Whatever your latitude, you'll find bright Jupiter about as high as Fomalhaut.

Saturday, Oct. 12

• Look above the nearly-full Moon this evening for the Great Square of Pegasus through the moonlight. It's balancing on one corner, and your fist at arm's length fits inside it. For your point on Earth, when it is exactly balanced? That is, when is the Square's top corner exactly above its bottom corner? This will probably by sometime soon after the end of twilight, depending quite a lot on your latitude. Try lining up the stars with the vertical edge of a building as a measuring tool.

Sunday, Oct. 13

• Full Moon (exact at 5:08 p.m. EDT). After dark, look high above the Moon for the Great Square of Pegasus standing on one corner.

• Cygnus the Swan flies nearly straight overhead these evenings. Its brightest stars form the big Northern Cross, usually visible even through bright moonlight. When you face southwest and crane your head up, the cross appears to stand upright. It's about two fists at arm's length tall, with Deneb as its top. Or to put it another way, the Swan is diving straight down.

Lower right of it, when you're facing southwest, shines bright Vega. Farther lower left is Altair.

Monday, Oct. 14

• This is the time of year when, in early to mid-evening, W-shaped Cassiopeia stands on end halfway up the northeastern sky — and when, off to its left, the dim Little Dipper extends leftward from Polaris in the north. Through the bright moonlight, 2nd-magnitude Polaris and Kochab (the Little Dipper's other end) may be all the stars of the Little Dipper you see... at first....

Tuesday, Oct. 15

• Now that it's mid-October, Deneb has replaced Vega as the zenith star after nightfall (for skywatchers at mid-northern latitudes).

Accordingly, dim Capricornus has replaced Sagittarius as the zodiacal constellation low in the south.

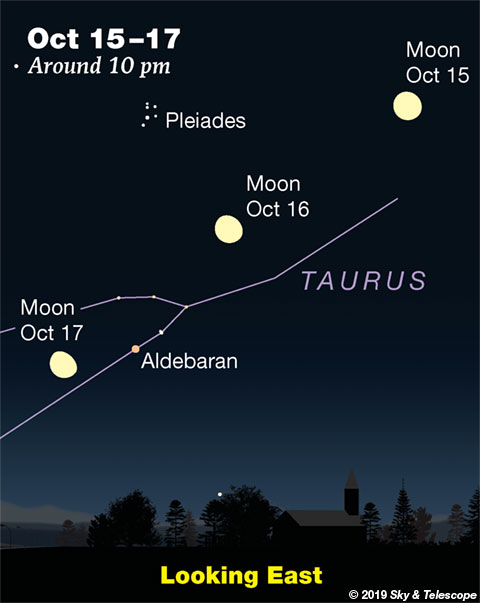

• Once the Moon is well up in the east, look to its left by about a fist and a half at arm's length for the little Pleiades cluster glimmering through the moonlight, as shown at the top of this page.

Wednesday, Oct. 16

• Now, as evening grows late, look for the Pleiades to the Moon's upper left and twinkly Aldebaran to the Moon's lower left, as shown at the top of this page.

Thursday, Oct. 17

• The waning gibbous Moon rises an hour or more after dark tonight, accompanied by orange Aldebaran 4° or 5° to its right. The Pleiades watch from above.

Friday, Oct. 18

• Vega is the brightest star high in the west after dark. To its lower right by 14° (nearly a fist and a half at arm's length), look for Eltanin, the nose of Draco the Dragon. The rest of Draco's fainter, lozenge-shaped head is a little farther behind. Draco always eyes Vega.

The main stars of Vega's own constellation, Lyra — quite faint by comparison — now extend to Vega's left (by 7°).

Saturday, Oct. 19

• Vega shines high in the west after dark. About equally high in the southwest is Altair, not quite as bright. Just upper right of Altair, by a finger-width at arm's length, spot little orange Tarazed. Down from Tarazed runs the stick-figure backbone of Aquila, the Eagle.

________________________

Want to become a better astronomer? Learn your way around the constellations. They're the key to locating everything fainter and deeper to hunt with binoculars or a telescope.

This is an outdoor nature hobby. For an easy-to-use constellation guide covering the whole evening sky, use the big monthly map in the center of each issue of Sky & Telescope, the essential guide to astronomy.

Once you get a telescope, to put it to good use you'll need a detailed, large-scale sky atlas (set of charts). The basic standard is the Pocket Sky Atlas (in either the original or Jumbo Edition), which shows stars to magnitude 7.6.

Next up is the larger and deeper Sky Atlas 2000.0, plotting stars to magnitude 8.5; nearly three times as many. The next up, once you know your way around, are the even larger Interstellarum atlas (stars to magnitude 9.5) and Uranometria 2000.0 (stars to magnitude 9.75). And read how to use sky charts with a telescope.

You'll also want a good deep-sky guidebook, such as Sue French's Deep-Sky Wonders collection (which includes its own charts), Sky Atlas 2000.0 Companion by Strong and Sinnott, or the bigger Night Sky Observer's Guide by Kepple and Sanner.

Can a computerized telescope replace charts? Not for beginners, I don't think, and not on mounts and tripods that are less than top-quality mechanically (meaning heavy and expensive). And as Terence Dickinson and Alan Dyer say in their Backyard Astronomer's Guide, "A full appreciation of the universe cannot come without developing the skills to find things in the sky and understanding how the sky works. This knowledge comes only by spending time under the stars with star maps in hand."

This Week's Planet Roundup

Mercury and Venus are very low in bright twilight after sunset. Start by trying for Venus, magnitude –3.9. It's just above the west-southwest horizon a mere 20 minutes after sunset. Binoculars will help.

Some 8° to its left is Mercury, much dimmer at magnitude –0.1 all week. That's only 3% as bright as Venus! Good luck with it; bring binoculars at a minimum.

Mars (magnitude +1.8) is a difficult catch just above the due-east horizon in early to mid- dawn. Again, you'll need binoculars.

Jupiter (magnitude –2.0, in the feet of Ophiuchus) is the white dot low in the southwest as twilight fades. To Jupiter's lower right by 11° or 12°, can you still spot Antares, one sixteenth as bright?

Jupiter is nearly on the far side of the Sun from us, appearing only 35 arcseconds wide in a telescope and very smushy in the low-altitude seeing.

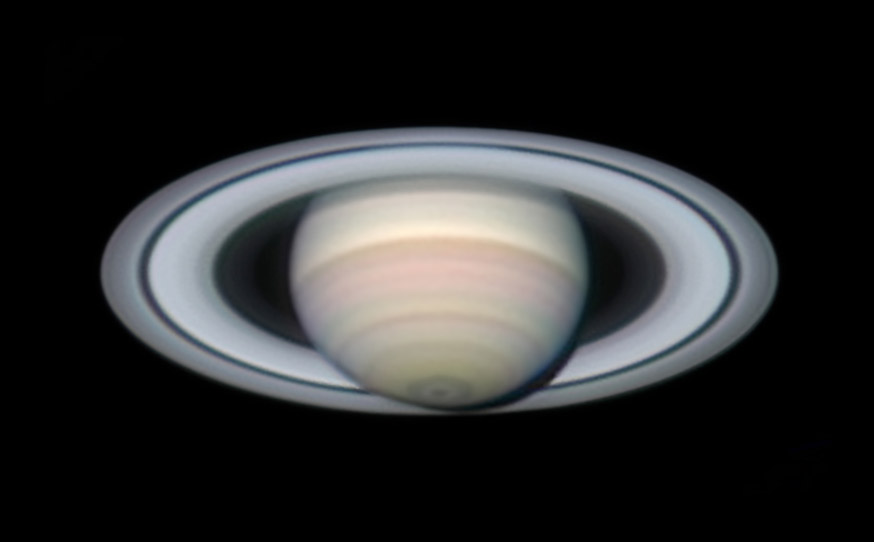

Saturn (magnitude +0.5, in Sagittarius) is the steady yellow "star" in the south-southwest during and after dusk. It's 24° upper left of Jupiter.

Saturn is just a week past its eastern quadrature with the Sun, so from our viewpoint, the planet's globe casts its shadow farthest eastward onto the rings, giving the whole arrangement its most 3-D appearance in a telescope. And the rings are tilted 25° into our line of sight, nearly as open as we ever see them.

Below Saturn is the handle of the Sagittarius Teapot, highlighted by 2.0-magnitude Sigma Sagittarii (Nunki). Barely above Saturn is the dimmer, smaller bowl of the Sagittarius Teaspoon.

Uranus (magnitude 5.7, in southern Aries) is well up in the east by 9 or 10 p.m. daylight saving time. It's highest in the south around 1 a.m.

Neptune (magnitude 7.8, in eastern Aquarius) is fairly well up in the southeast right after dark and highest in the south by 10 p.m. See Bob King's story on observing Neptune and our finder charts for Uranus and Neptune.

All descriptions that relate to your horizon — including the words up, down, right, and left — are written for the world's mid-northern latitudes. Descriptions that also depend on longitude (mainly Moon positions) are for North America.

Eastern Daylight Time (EDT) is Universal Time (UT, UTC, GMT, or Z time) minus 4 hours.

![]() Audio sky tour. Out under the evening sky with your earbuds in place, listen to Kelly Beatty's monthly podcast tour of the heavens above. It's free.

Audio sky tour. Out under the evening sky with your earbuds in place, listen to Kelly Beatty's monthly podcast tour of the heavens above. It's free.

"The dangers of not thinking clearly are much greater now than ever before. It's not that there's something new in our way of thinking, it's that credulous and confused thinking can be much more lethal in ways it was never before."

— Carl Sagan, 1996

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.