Twilight's end brings the return of the summer Milky Way to the eastern sky. We unravel the anatomy of our home galaxy by teasing out the hidden structures within that glowing band.

Illustration by James Gordon Irving

Stars, a Golden Guide written by Herbert Zim and Robert Baker, was the go-to night-sky book for kids back when I was one. I still have my copy, a 12th printing dated 1960, that's in better shape than I am. One of the book's best illustrations, by James Gordon Irving, depicts a man and woman standing together under the constellations of the spring sky, a hazy blue Milky Way rising along the eastern horizon. Irving captured the enchantment of a shared starlit evening and the anticipation of that great band of starry light returning to view.

I fell in love with that picture, and it still stirs up good feelings, as if a great adventure lies ahead. Maybe that's why I'm eager to see the Moon depart the evening sky this week and watch the Milky Way climb the eastern sky, so we can revel again in its sumptuous stars.

Bob King

We all enjoy a starry night, but the Milky Way provides a sense of scale like no other naked-eye sight. Just the sweep of it! You know you're looking at something really, really big — and grand — like a mountain range at sunset but on a cosmic scale. It forces you to stop and take stock. To remind us there's beauty all around.

NASA / JPL-Caltech / R. Hurt (SSC / Caltech) / E. L. Wright (UCLA) (left) / The COBE Project / DIRBE / NASA with additions by the author (right)

All that good stuff is back again. You only need a dark sky to the east and the will to stay up past your normal bedtime, a familiar expectation of summertime skywatching.

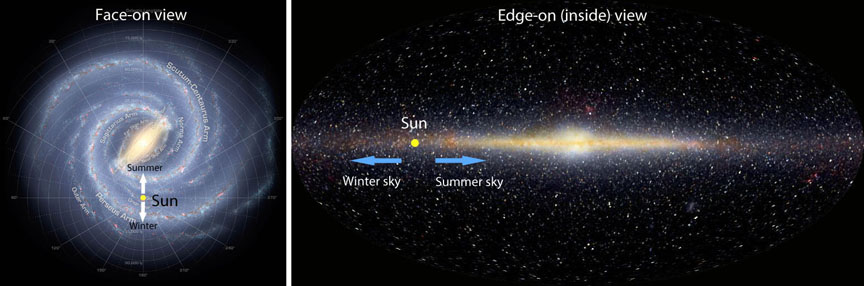

We live in a barred spiral galaxy about 100,000 light-years wide shaped like a pancake with a bulge in the middle. It's home to at least 200 billion stars and an estimated 100 billion planets. The Sun and planets orbit within the 1,000-light-year-thick disk near the mid-point of the galactic plane, 26,000 light-years from the central bulge. Because we're stuck inside the galaxy, we can only ever see it edge-on, never face-on, a view reserved for stars orbiting above or below the galactic plane. For a musical description of the Milky Way Galaxy, listen to Monte Python's Galaxy Song.

So, what do we see exactly when we look at the band of the Milky Way?

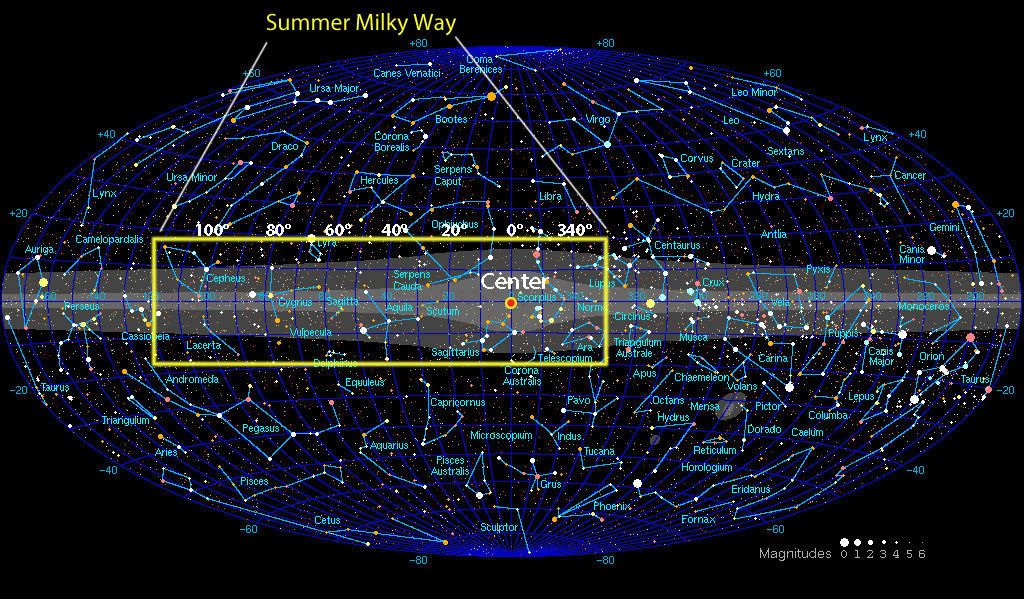

Stellarium

Although our edge-on perspective prevents a view of the galactic core due to intervening dust, it's responsible for the magnificent band of the Milky Way, a perspective effect from looking through the disk and seeing billions of stars stack up over vast distances to create a ribbon of glowing haze across the sky. When we look above or below the band, which defines the galactic plane, we're looking out of the galaxy. That's the reason the stars thin out rapidly and also why the band has a well-defined edge. Stars are concentrated in the disk and core; they dwindle quickly once our gaze soars above the plane.

ESO

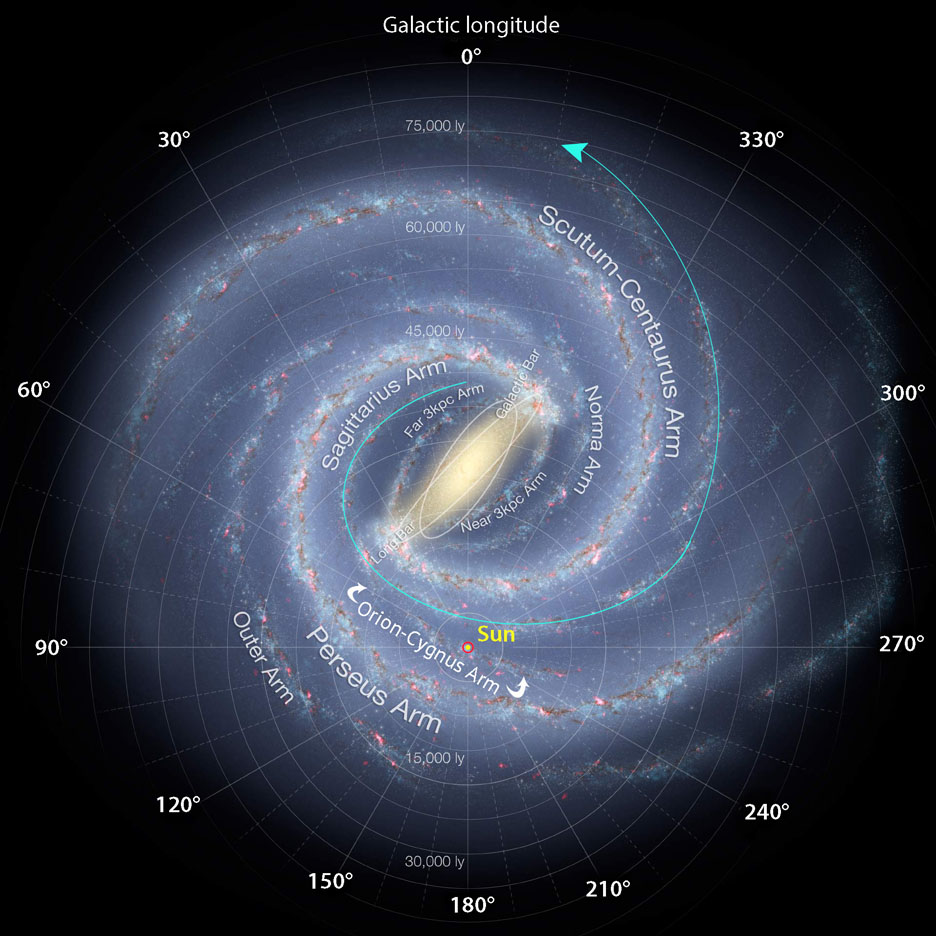

Locations of objects within the Milky Way are described by their galactic latitude and longitude with the Sun as the center point. The line connecting the Sun through the center of the galaxy defines the galactic equator (0° latitude), while the direction from the Sun to the galactic center serves as 0° longitude point. The other longitudes are arranged around the galactic circle in the diagram above similar to a compass. The galactic north and south poles at +90° and –90° lie far above and below the galaxy's plane.

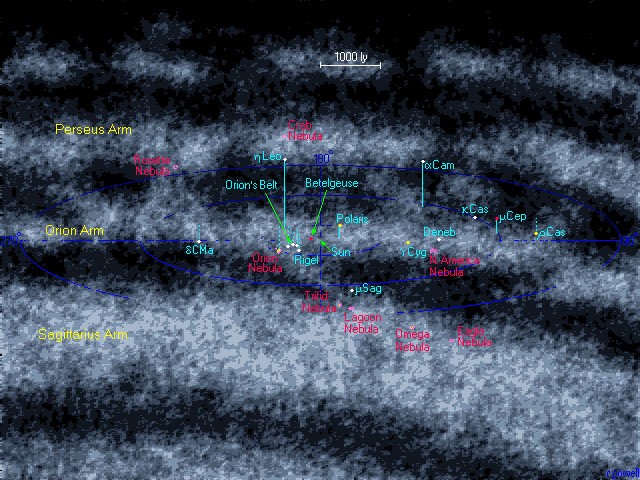

Richard Powell with additions by the author

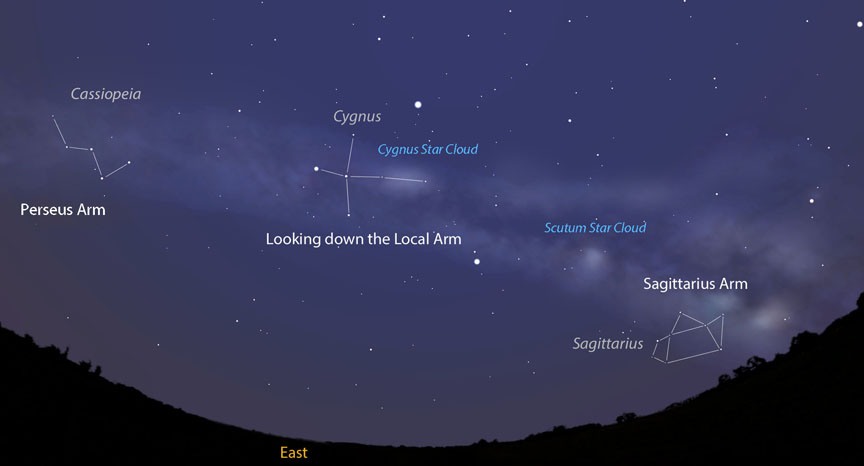

On winter nights we look outward toward the Perseus and Outer Arms between about 120° and 240° longitude centered on the galactic anticenter (180°) directly opposite the core. But in summer we face inward toward the galactic core, toward 0° longitude in the direction of the constellation Sagittarius. As our gaze sweeps from Cassiopeia and Cepheus in the northeastern sky to Sagittarius in the southeast, we first look "over our shoulder" into the Perseus Arm toward Cassiopeia (130° – 110°). Then our eyes glide effortlessly across an inter-arm gap until we arrive at our local arm called the Orion–Cygnus Arm or the Orion Spur. Minor though it may be, it still extends an impressive 10,000 light-years.

Yuri Beletsky / Las Campanas Observatory / Carnegie Institution

Looking down the local arm, the Milky Way thickens in Cygnus (90°– 60°) as stars bunch up along our line of sight to make such notable spectacles as the Cygnus Star Cloud. You can't miss this bulbous glow tucked between Gamma (γ) Cygni and Albireo — it's one of the brightest sections of the summertime Milky Way and a great place for star-sweeping with a small telescope or binoculars.

Richard Powell

From Cygnus we slide southward to Aquila and Scutum, crossing into the Sagittarius Arm, the outermost of the galaxy's inner arms. Lots of highlights here! One of the best is the Scutum Star Cloud, a strawberry-shaped glitter-puff about 5° across located 6,000 light-years away. It's home to the Wild Duck Cluster (M11) and numerous dark nebulae. The Lagoon Nebula (M8), the Eagle (M16), the Omega Nebula (M17), and Carina Nebula and many more of our favorite deep sky objects reside in the Sagittarius Arm.

Bob King

Next in is a massive Scutum-Centaurus Arm. While there may be faint fuzzies and stars visible in amateur telescopes within this distant galactic furl, I'm not aware of any. Clouds of interstellar dust mucking about the plane of the Milky Way hide distant stars and nebulae except in rare cases. One of those scarce portholes is Baade's Window, a 1°-wide clearing just above the tip of the Sagittarius Teapot, that will shoot you across 25,000 light-years straight into the core of the galaxy!

Truth to tell, cosmic dust and the natural dimming of stars across great distances means we only see a bubble's worth of space from our perch midway in the Milky Way. Maybe out to 5,000 light-years or so with the naked eye. Much of the galaxy is obscured or lies beyond visibility. And yet it's enough to set your soul sailing off to great adventures on a dark summer night.

21

21

Comments

Rod

June 19, 2019 at 2:52 pm

Bob, very good report. *Duluth, Minnesota*, the picture shows a very good view of the Milky Way from your observing site, much better than where I am at in Maryland. I see hints and portions running through Cygnus to Sagittarius, mostly later at night when the constellations are higher up and stars visible down to about mv +5.5. Some of my favorite targets are M11, M8, and M22, the globular cluster. Using my 10-inch telescope - I enjoy excellent views. Albireo as a double star is very lovely too with my 90-mm refractor. Enjoy your Milky Way skies at Duluth this summer. Lately, I am enjoying periodic rain showers, t-storms, and haze along with much grass cutting and weed whacking. Perhaps *mostly clear* on Friday night here - I have seen this forecast before too 🙂

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

June 19, 2019 at 3:52 pm

Thanks, Rod. Those are some of my favorites, too. A clear sky Friday would be ideal — no moon till after midnight.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Kerbal9

June 20, 2019 at 2:38 am

Oh, you know, my english isn't good, but i enjoy reading this article, thank you!

For my case, Russia 57 degree latitude, I'll not see Milkyway for a long time. I think no earlier than august. At midnight we have the Sun only about 10 degrees below horizon now, I only can see stars brighter than mag 4 with naked eye.

May i ask you a queston about telescope? I have 8" reflector (Skywatcher P2001EQ5). With a star mag 3 i can see at least 5 circles Airy pattern (with 400x magnification, 5mm eyepiece + barlow). I suspect that isn't good, but don't know exactly. Is it normal or my scope is low quality?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Rod

June 20, 2019 at 10:34 am

Kerbal9, I observe in Maryland near 38.8 degrees north latitude and use 90-mm refractor and 10-inch reflector telescope. My 10-inch in theory can view at 400x but recommended views by the eyepiece vendor - 300x or less. I find looking at targets 30 degrees or higher altitude better views too. Most of my observations range about 31x to 215x views. Planets like Jupiter and Saturn do at times show thermal currents because of the atmosphere but mostly - very good views, especially near transit times for my location.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Kerbal9

June 20, 2019 at 12:37 pm

Thank you for reply, Rod! I'm trying to say that there is no matter about turbulence or thinks like this, it's like a 'star test' of optics quality itself. I have only one scope, so i don't have a good opportunity to compare aberrations one and another.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

June 20, 2019 at 11:17 am

Dear Kerbal,

Your English is just fine. Seeing five circles in the Airy pattern is a good thing. If you can see the same pattern both inside and outside of focus your optics are excellent.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Kerbal9

June 20, 2019 at 12:45 pm

Thank you for quick answer!

Actualy, i tried to focus on and focus out with one bright star in view, and sadly there was a difference. But it's hardly to find out how bad my optics is, more or less. I thought, the reason is central obscuration.

Well, I need more exprerience with scopes!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

June 20, 2019 at 1:56 pm

Kerbal,

If inside and outside focus weren't exactly the same, don't give up! In most of my telescopes they're rarely the same, but the views are still very, very good.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

TomR

June 21, 2019 at 4:10 am

I’ve read, that the word cosmos has the same Greek origin as cosmetics, meaning order, system or harmony.

Thomas, Austria

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

June 21, 2019 at 6:40 pm

Hi Tom,

I never thought about that — thanks for the insight. Additional meanings include "adorn" or "arrange." Wonderful how they share the same root.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Greg Furtman

June 21, 2019 at 6:29 pm

Hi Bob,

So if we were in space in the shadow of something, would we see the Milky Way as a ring around us? I've always wondered.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

June 21, 2019 at 6:37 pm

Hi Greg,

Yes — and you don't necessarily need to be in a shadow. Just out floating in space, say between the Earth and the moon. Anywhere where you could twist around and look up, around and down. Nice to hear from you here 🙂

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Glenn

June 21, 2019 at 10:14 pm

I have a recent edition of "Stars" purchased in 2017 with a 2001 copyright. Same picture as you showed is on p 62-63. Living in a childs dream goes the song. Sigh. It is very similar to The Giant Golden Book of Astronomy by Wyler and Ames with illustrations by Polgreen. Still have my copy of the eleventh printing in 1960 with a forward by Bart J. Bok................... Glenn

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

June 22, 2019 at 11:19 am

Hi Glenn,

I think I have a copy of that, too. Sometimes these "childs' dreams" can inspire a life.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

ashleyl131

June 22, 2019 at 9:55 am

Thoroughly enjoyed reading your article, Bob. It provided such an excellent understanding of what we see when looking at the Milky Way. I am now eager to spend my summer in Montana, staying up late, to see this beautiful sky. Will use this article as a guide. Thanks!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

June 22, 2019 at 11:21 am

Hi Ashley,

Thank you, and I'm happy you enjoyed it! Wishing you lots of clear nights to take in the big picture 🙂

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Anthony Barreiro

June 22, 2019 at 5:27 pm

Thanks very much, Bob.

I got serious about skywatching fairly late in life, around 40 years old. The May 2000 alignment of all the naked-eye planets in evening twilight was my immediate inspiration. Following the Moon and planets taught me the zodiacal constellations, and then of course I wanted to learn the names of the other bright stars, and one thing led to another. After a few years I had a visceral aha moment when I really got that the stars are out there in three dimensions, not just arrayed on the celestial sphere. I wanted to know where they all are in space, and that prompted more disciplined study.

In Sky and Telescope July and October 2013 and February 2014, Craig Crossen wrote a very helpful guide to observing the Milky Way. The July article included a beautiful fold-out map. I saved those issues and still refer to them.

One thing that helps me get oriented in the sky is to relate the celestial equator to the ecliptic and both of them to the plane of the galaxy. That they're all different planes is proof that God is not an engineer! 😉

It's now greatly satisfying to look up at the sky, even through horrible urban light pollution, and have a sense of where we are in our solar system and our galaxy (and even where our galaxy is in relation to other galaxies). Knowing that all the familiar stars in the sky are simultaneously both inconceivably far away *and* our immediate neighbors is mind-blowing, humbling, and oddly comforting. It puts our human travails into perspective.

Anyway, thanks again. Hopefully I'll get out under a dark sky this summer and be blessed with good weather.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Bob KingPost Author

June 22, 2019 at 9:42 pm

Anthony,

I so enjoy reading your comments. Thank you. I wanted to mention that the plane of the ecliptic is so different from the tilt of the galaxy but held off for fear of making the article too long. Maybe I'll sneak it in there somehow. It was a revelation when it finally hit me why the Milky Way appears tilted the way it does. God may still be an engineer but one with a special fondness for the Rube Goldberg approach. Did you know that Goldberg was also an engineer (among other things.)

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Anthony Barreiro

June 22, 2019 at 11:10 pm

The universe as a Rube Goldberg device? That would explain a lot! I didn't know Goldberg was an engineer, but it makes sense. 🙂

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Rod

June 24, 2019 at 10:03 am

Anthony, you said "It’s now greatly satisfying to look up at the sky, even through horrible urban light pollution, and have a sense of where we are in our solar system and our galaxy (and even where our galaxy is in relation to other galaxies). Knowing that all the familiar stars in the sky are simultaneously both inconceivably far away *and* our immediate neighbors is mind-blowing, humbling, and oddly comforting." I agree, this knowledge in astronomy was difficult to achieve and hard won in the debates between the geocentric universe world vs. the heliocentric solar system and finally, stellar distances using parallax. Even today, there are some stars whose distances are difficult to determine as my observation note demonstrates. While I viewed Jupiter last night, there was a star visible in the field of view (FOV) close to Jupiter and the Galilean moons. From my livesky log "This star near 10:30 position of Jupiter in mirror reverse view at 129x tonight. Good position fix of Jupiter retrograding in Ophiuchus. About 15 arcminute (15') angular separation from Jupiter in the FOV. The FOV about 0.56-degree. Starry Night shows 870 LY distance, Stellarium 0.19.0 shows 1812 LY distance, and SIMBAD portal stellar parallax of 4.7687 mas is 684 LY distance from Earth. SIMBAD portal shows HIP83629 is also HD 154293." Indeed, understanding our place in the universe is important and astronomy knowledge can help.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Anthony Barreiro

June 24, 2019 at 5:29 pm

Yeah, we need to take all these distances with a grain of salt. The ESA spacecraft Gaia is measuring stellar parallaxes. proper motions, and radial velocities with unprecedented accuracy. Gaia is giving us a much better three dimensional map of our galaxy than we have ever had before.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.