January 3, 2005

Contact:

Alan MacRobert, Senior Editor

855-638-5388 x151, [email protected]

Marcy McCreary, VP Mktg. & Bus. Dev.

855-638-5388 x143, [email protected]

Note to Editors/Producers: This release is accompanied by high-quality graphics; see details below.

It won't knock your eyes out — in fact you'll probably need binoculars to see it — but a new comet is glowing high up among the sparkling winter stars. Comet Machholz is the brightest in several years to appear high in the evening sky for observers in North America and Europe. Named for its discoverer, amateur astronomer Don Machholz of Colfax, California, it's barely visible to the naked eye if you get away from city light pollution and know exactly where to look.

However, a pair of binoculars will show the comet from practically anywhere at all. Even if you've never located anything in the sky before and don't know Polaris from Pluto, you can find the new comet for yourself and have a look. Here's how.

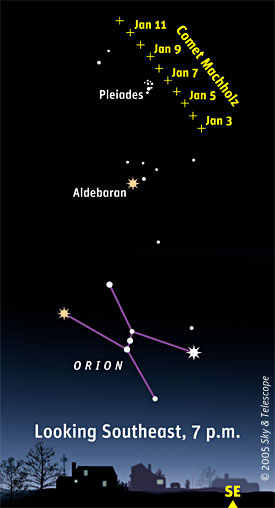

Go out after dinnertime on the next clear night, find a spot with no lights nearby, and look southeast. Glittering there will be the bright constellation Orion, as shown on the accompanying chart. High above Orion you'll notice the orange star Aldebaran. Even higher above Aldebaran is the little Pleiades star cluster, the size of your fingertip seen at arm's length. You should have no trouble spotting any of these.

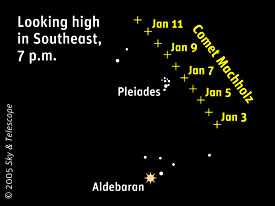

The comet is moving night by night. On the accompanying chart, its position is marked for each evening in early January. Note the exact position of tonight's symbol with respect to Aldebaran and the Pleiades. In other words, memorize the shape of the triangle that the comet makes with Aldebaran and the Pleiades. Go outdoors, give your eyes a few minutes to adapt to the dark, and examine this spot with your binoculars.

There the comet will be: a dimly glowing ball of haze floating among the pinpoint stars, luminous gray with a touch of aquamarine green. It will probably display a brighter core and possibly, if your sky is dark enough, a hint of a tail. Make a special note to look on January 7th, when the comet will be right next to the Pleiades.

A few tips: For your eyes to become dark adapted you need to be in the dark for at least 5 or 10 minutes, preferably 20 or more. The bigger the front lenses of your binoculars are, the better. And, of course, the farther you are from urban lights the better. But even in the city, binoculars should show at least the comet's inner part if you can get to a shaded nook or a rooftop above the streetlights.

If you've got (or can borrow) a telescope, do try it out — after you've located the comet without it. Use the telescope's lowest magnification to get the widest field of view.

Like all comets, Machholz is a dirty iceberg that has fallen from the solar system's cold outer reaches into the warm inner region that we inhabit. Here the warmth of the Sun is strong enough to heat the comet's surface. The glow that you see is the huge, thin cloud of sunlit gas and dust evaporating from the relatively tiny iceberg at the center.

Comet Machholz is currently the closest significant object to Earth after the Moon. It will be at its best during the first half of January. Then bright moonlight will interfere with the view somewhat, from about January 15th to 27th. But even during and after this period, the comet will still be well placed in good view — though starting to fade as it moves farther from the Earth and Sun. It will remain visible in binoculars during February and in good amateur telescopes through March, April, and May.

More information about Comet Machholz, charts of its position through May, and the story of Don Machholz's discovery of it last August 27th are in the January 2005 issue of Sky & Telescope. See also the articles linked below.

Don Machholz has been hunting comets since 1975; this is his tenth discovery. Today, automated sky-search projects using robotic telescopes make an increasing percentage of comet discoveries, and as a result, many comets now get named with acronyms of projects such as LINEAR, NEAT, and ASAS. But this one showed that there's still room for a diligent amateur to get there first.

However, it's getting tough. Machholz made his last discovery in 1994, and he logged 1,458 hours of comet-searching time before he caught this one!

Sky & Telescope is pleased to make the following photograph and illustrations available to the news media. Permission is granted for one-time, nonexclusive use in print and broadcast media, as long as appropriate credits (as noted in each caption) are included. Web publication must include a link to SkyandTelescope.com.

Use this handy chart to locate Comet Machholz high in the southeast after dark in early January 2005. Click on the picture to download a high-resolution version (125-kilobyte JPEG) by anonymous FTP.

Sky & Telescope illustration by Steven A. Simpson.

Use this handy chart to locate Comet Machholz high in the southeast after dark in early January 2005. Click on the picture to download a high-resolution version (99-kilobyte JPEG) by anonymous FTP.

Sky & Telescope illustration by Steven A. Simpson.

Comet Machholz glows among faint stars in the constellation Taurus on Saturday evening, January 1, 2005. Shot through a small telescope with a digital camera, this photo shows the comet pretty much as it appears to the eye in binoculars. Click on the picture to download a high-resolution version (2.3-megabyte JPEG) by anonymous FTP.

Sky & Telescope photo by Gary Seronik.

Sky Publishing Corp. was founded in 1941 by Charles A. Federer Jr. and Helen Spence Federer, the original editors of Sky & Telescope magazine. The company's headquarters are in Cambridge, Massachusetts, near the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. In addition to Sky & Telescope and SkyandTelescope.com, the company publishes Night Sky magazine (a bimonthly for beginners with a Web site at NightSkyMag.com), two annuals (Beautiful Universe and SkyWatch), as well as books, star atlases, posters, prints, globes, and other fine astronomy products.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.