Contacts:

Diana Hannikainen, Observing Editor

855-638-5388 x22100, [email protected]

J. Kelly Beatty, Senior Contributing Editor

617-416-9991, [email protected]

| Note to Editors/Producers: This release is accompanied by publication-quality illustrations; see details below. |

If it’s clear the nights of Thursday and Friday, December 13th and 14th, step outside and look up — you may very well see streaks of light across the sky from the annual Geminid meteor shower.

Although the Perseids, which arrive each August, are better known, the Geminids often put on a better show. “Maybe because it’s cold for so many during this shower’s peak,” says Diana Hannikainen, observing editor at Sky & Telescope. “But the Geminids are often the best display of ‘shooting stars’ all year.”

Sky & Telescope predicts that the Geminids should peak around 7:30 a.m. EST (4:30 a.m. PST) on December 14th. So observers in North America will see the most meteors in the dark hours before dawn that day.

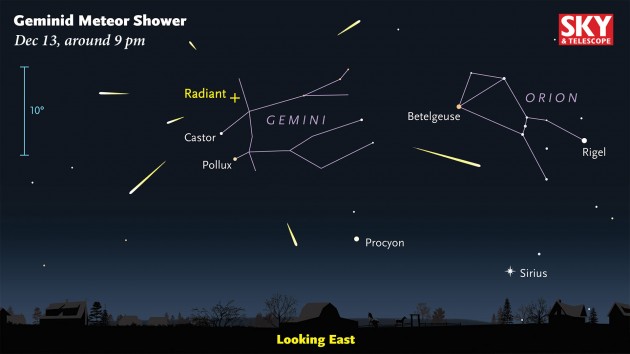

If you're not a "morning person," you can start looking a few hours after sunset on the 13th or 14th. The shower’s radiant — the perspective point in the sky from which all meteors appear to emanate — is near the relatively bright star Castor in the constellation Gemini. For viewers at mid-northern latitudes, the radiant is well above the eastern horizon by around 9 p.m. local time and stands highest around 2 a.m.

The waxing crescent Moon sets around 10:30 p.m. on December 13th and about a half hour later on the 14th. So if you’re looking for meteors before then, make sure you keep the Moon at your back as you scan the skies. If you can, get outside before dawn (or stay up late), so you can watch for meteors without interference from moonlight.

The number of meteors you see will depend very much on the darkness of your location, and what time you’re out looking for them. “If you’ve got a clear, dark sky with no light pollution, you might see a meteor streak across the sky every minute or two from 10 p.m. until dawn on the night of the peak,” says Hannikainen.

The shower’s maximum is broad, with lower counts on the nights preceding and following the peak — fainter meteors are more abundant ahead of the peak, brighter ones after the peak. So if you happen to be outdoors in the evenings or very early mornings during the week before and after December 14th, it’s worth casting your gaze skyward to see if you catch any Geminids.

How to Watch for Geminids

Meteor-watching is easy — you need no equipment other than your eyes. But you'll see more of them if you allow at least 20 minutes after going outside for your eyes to adapt to the darkness. Find a dark spot with an open view of the sky and no glaring lights nearby. Bundle up as warmly as you can in many layers. “Go out in the evening, lie back in a reclining lawn chair, and gaze up into the stars,” advises Hannikainen. “With the radiant rising in the evening, this is a good shower for younger observers who may have earlier bedtimes. But as always, it’s good to remember to be patient.”

Geminids can appear anywhere in the sky, so the best direction to watch is wherever your sky is darkest, probably straight up. Small particles create tiny, quick streaks. The occasional bright one might leave a brief train of glowing smoke. The few that you may see early in the evening will be longer, dramatic steaks continuing for a few seconds as they graze sideways through Earth's uppermost atmosphere.

The Source of the Geminid Meteors

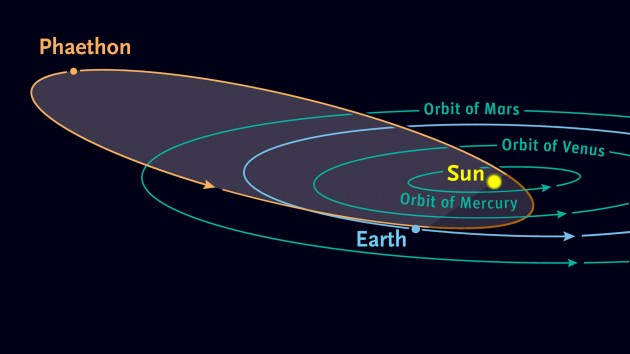

The last major meteor shower of the year is brought to us courtesy of 3200 Phaethon, a unique asteroid referred to as a rock comet since it shares characteristics with both asteroids and comets. The Geminids were first reported in 1862 and have been recognized as an annual phenomenon since then, but the source of the shower was unknown until 1983 when Phaethon was discovered.

Phaethon is small, only about 3 miles across, and it loops around the Sun every 1.4 years in an orbit that approaches the Sun closer than any other known asteroid. Rock comets eject material consisting of rocky dust rather than the ice-related vapors typical of comets. Phaethon sheds this dusty debris about the size of sand grains or peas each time it nears the Sun, when its surface gets heated to roughly 1,300°F (700°C).

Over the centuries, these bits of Phaethon have spread all along the asteroid’s orbit to form a sparse, moving “river of rubble” that Earth passes through in mid-December each year. The particles are traveling 22 miles per second (79,000 mph) with respect to Earth at the place in space where we encounter them. So when one of them dives into Earth’s upper atmosphere, about 50 to 80 miles up, air friction vaporizes it in a quick, white-hot streak.

More about Light Pollution

Light pollution in the sky doesn’t interfere just with meteor watching. It’s the bane of everyone from backyard nature lovers to professional deep-space researchers. But most light pollution is unnecessary. It results from wasted light beamed uselessly sideways or upward from all of the poorly designed and improperly aimed outdoor lighting for many miles around.

This waste can be prevented by installing modern, fully shielded fixtures, and by aiming fixtures more downward toward the ground where the light is wanted. These simple steps not only reduce light pollution in the sky but also allow great savings of electricity. "Be aware that some LED fixtures emit harsh, blue-hued light that makes it especially difficult to see the stars," notes S&T senior contributing editor Kelly Beatty. To avoid this harshness, the International Dark-Sky Association recommends that you install LEDs with a "color temperature" (marked on the packaging) that's no greater than 3000K.

Sky & Telescope is making a publication-quality illustration available to our colleagues in the news media. Permission is granted for one-time, nonexclusive use in print and broadcast media, as long as appropriate credit (as noted in the caption) is included. Web publication must include a link to SkyandTelescope.org.

Sky & Telescope / Gregg Dinderman

Sky & Telescope / Alan Dyer

Sky & Telescope diagram

0

0