December 7, 2004

Contact:

Alan MacRobert, Senior Editor

855-638-5388 x151, [email protected]

Marcy McCreary, VP Mktg. & Bus. Dev.

855-638-5388 x143, [email protected]

Note to Editors/Producers: This release is accompanied by two high-quality animations and an illustration; see details below.

A Line of Planets

For a few days in mid-December 2004, the planets Mercury through Pluto are arranged from east to west in Earth's sky in the same order that they're positioned outward from the Sun. This situation begins when Mercury passes inferior conjunction (between the Sun and Earth) on December 10th, and it ends when Pluto leaves the evening sky on the 13th. Only the planets Venus through Saturn are observable with the unaided eye on these nights, with Uranus and Neptune visible in binoculars and telescopes. Both Mercury and Pluto are hidden in the Sun's glare.

Such a lineup is rarer than a transit of Venus. Apart from a similar brief interval in November 2002, the planets have not been arrayed in their natural order westward from the Sun since before the invention of the telescope, and they won't be again for at least four centuries.

A line of planets stretching to the east of the Sun is equally rare. This occurred in late February and March 1801, and it won't happen again until April 2333!

December Meteors

Immediately after the planet parade, an old, reliable meteor shower heads our way. The annual Geminids should reach peak activity late on the night of December 13–14 (late Monday night and early Tuesday morning).

Along with the better-known Perseids of August, the Geminids are the strongest of the reliable annual meteor showers that hardly change from year to year. Sky & Telescope magazine predicts that late on the peak night, you might see a "shooting star" every few minutes on average.

The time to watch will be anytime from about 10 p.m. Monday evening, December 13th, until the first light of dawn on Tuesday morning. This year there's no glare from moonlight to worry about, because the Moon is a two-day-old crescent that sets early Monday evening.

You’ll need no equipment but your eyes. Find a dark spot with an open view straight up and no bright lights nearby to spoil your night vision. Bring a reclining lawn chair, bundle up warmly, and bring a sleeping bag; clear nights get very cold.

"Just lie back and watch the stars," says Sky & Telescope senior editor Alan MacRobert. "Relax and let your eyes adapt to the dark. Be patient."

With a little luck you’ll see a Geminid every few minutes on average. They’ll appear as often as once a minute if you have a dark sky far from the light pollution (skyglow) that hangs above populated areas.

Faint Geminids appear as tiny, quick streaks. Occasional brighter ones, often appearing yellow, may sail across the heavens for several seconds, leaving brief trains of glowing smoke.

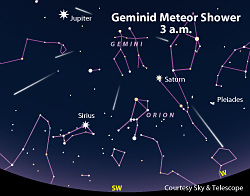

If you trace each meteor’s direction of flight backward far enough across the sky, you’ll find that the imaginary line you’re drawing crosses a spot in the constellation Gemini near the stars Pollux and Castor. This spot is the shower’s radiant, the perspective point from which all the Geminids would appear to come if you could see them approaching from the far distance. The radiant is well up in the east by 10 p.m., nearly overhead around 2 a.m., and high in the west by the first light of dawn. But you don’t have to look there. Just watch whatever part of your sky is darkest.

The Geminid shower is active for several days, not just on its peak night. You may see a few meteors for two or three nights beforehand and one night after.

The Geminid meteoroids (particles) are tiny, sand-grain- to pea-size bits of rocky debris that have been shed by a small asteroid named Phaethon. Over the centuries these bits have spread all along the asteroid’s orbit to form a sparse, moving "river of rubble" hundreds of millions of miles long. Earth’s own annual orbit around the Sun carries us through this stream of particles every mid-December.

The particles are traveling 22 miles per second with respect to Earth at the place where we encounter them. So when one of them strikes the Earth’s upper atmosphere (about 50 to 80 miles up), air friction vaporizes it in a quick, white-hot streak.

Amateur meteor watchers who have dark skies and are willing to follow careful guidelines can carry out scientifically valuable meteor counts, as described on Sky & Telescope's Web site at http://SkyandTelescope.com/observing/objects/meteors/article_98_1.asp.

Sky & Telescope is pleased to make the following illustration and animations available to the news media. Permission is granted for one-time, nonexclusive use in print and broadcast media, as long as appropriate credits (as noted in each caption) are included. Web publication must include a link to SkyandTelescope.com.

This is a reduced-size frame from Sky & Telescope's broadcast-quality QuickTime animation (TRT 13:00) simulating the appearance of the Geminid meteor shower at 3:00 a.m. on December 14th. Use anonymous FTP to download the complete animation (7 kilobytes) or a publication-quality JPEG version (206 kilobytes) of this illustration.

S&T: Gregg Dindermann

These are reduced-size frames from Sky & Telescope's broadcast-quality QuickTime animation showing how a meteor is formed when a speck of debris burns up in Earth's upper atmosphere. Click on the image to download the full animation (17 megabytes) by anonymous FTP.

S&T: Steven A. Simpson.

Sky Publishing Corp. was founded in 1941 by Charles A. Federer Jr. and Helen Spence Federer, the original editors of Sky & Telescope magazine. The company's headquarters are in Cambridge, Massachusetts, near the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. In addition to Sky & Telescope and SkyandTelescope.com, the company publishes Night Sky magazine (a bimonthly for beginners with a Web site at NightSkyMag.com), two annuals (Beautiful Universe and SkyWatch), as well as books, star atlases, posters, prints, globes, and other fine astronomy products.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.