October 24, 2003

Contacts:

Alan MacRobert, Senior Editor

855-638-5388 x151, [email protected]

Marcy L. Dill, Marketing Director

855-638-5388 x143, [email protected]

Note to Editors/Producers: This release is accompanied by high-quality graphics and an animation; see details on page 2. Also, see below for information about this year's Leonid meteor shower on November 17–18.

On Saturday night, November 8–9, 2003, the full Moon will pass through the Earth's shadow for skywatchers throughout the Americas, Europe, and Africa, and in parts of Asia. For the Americas, this will be the second lunar eclipse of 2003; the first took place the night of May 15–16.

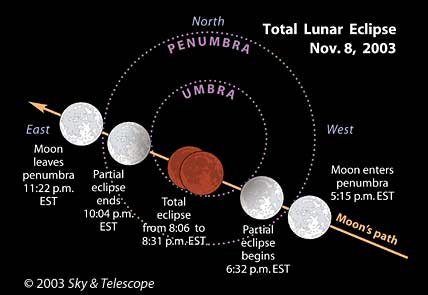

But the total phase of November's eclipse will be unusually brief, lasting only 25 minutes as the Moon skims barely inside the southern edge of our planet's dark shadow.

Skywatchers in eastern North America will see the entire eclipse during dark evening hours. Those living in the western half of North America will find the eclipse already in progress as the Moon rises around sunset.

All of Europe and most of Africa will see the eclipse in its entirety much later Saturday night. Observers in eastern and southern Africa, the Middle East, and southern Asia will see the eclipsed Moon set around sunrise on Sunday morning.

| Total Eclipse of the Moon, November 8–9, 2003 | |||||

| Eclipse stage | UT* | EST | CST | MST | PST |

| Moon enters penumbra | 22:15 | 5:15 p.m. | — | — | — |

| First shading visible? | 22:55 | 5:55 p.m. | 4:55 p.m. | — | — |

| Partial eclipse begins | 23:32 | 6:32 p.m. | 5:32 p.m. | — | — |

| Total eclipse begins | 1:06 | 8:06 p.m. | 7:06 p.m. | 6:06 p.m. | — |

| Total eclipse ends | 1:31 | 8:31 p.m. | 7:31 p.m. | 6:31 p.m. | 5:31 p.m. |

| Partial eclipse ends | 3:04 | 10:04 p.m. | 9:04 p.m. | 8:04 p.m. | 7:04 p.m. |

| Last shading visible? | 3:45 | 10:45 p.m. | 9:45 p.m. | 8:45 p.m. | 7:45 p.m. |

| Moon leaves penumbra | 4:22 | 11:22 p.m. | 10:22 p.m. | 9:22 p.m. | 8:22 p.m. |

| *UT stands for Universal Time, essentially the same as Greenwich Mean Time. | |||||

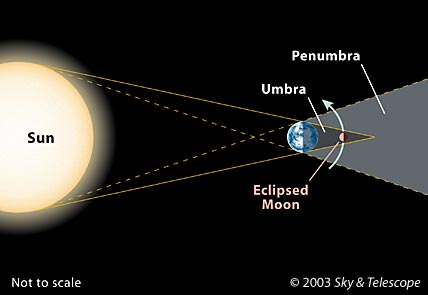

A total lunar eclipse occurs when the Sun, Earth, and Moon form a nearly straight line in space, so that the full Moon passes through Earth's shadow. Unlike a solar eclipse, which requires special equipment to observe safely, you can watch a lunar eclipse with your unaided eyes. Binoculars or a small telescope will enhance the view dramatically.

As the Moon moves into the outer fringe, or penumbra, of Earth's shadow, it will fade very slightly — imperceptibly at first. Only when the leading edge of the Moon is at least halfway into the penumbra is any shading visible at all.

The real show starts when the Moon's leading edge first enters the shadow's dark core, or umbra, and the partial eclipse begins. For the next hour and 34 minutes, more and more of the Moon will slide into dark shadow.

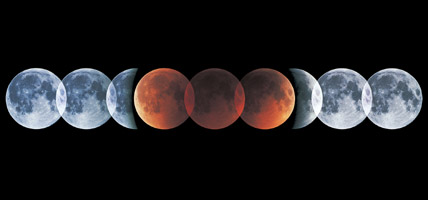

The total eclipse begins when the Moon is fully within the umbra. But it likely won't be blacked out. The totally eclipsed Moon should linger as an eerie dark gray or coppery red disk in the sky, as sunlight scattered around the edge of our atmosphere paints the lunar surface with a warm glow. This is light from all the sunrises and sunsets that are in progress around Earth at the time.

Each total lunar eclipse is different. Sometimes the Moon looks like an orange glowing coal, while at other times it virtually disappears from view. Its brightness depends on the amount of dust in the Earth's upper atmosphere at the time, which influences the amount of sunlight that filters around the Earth's edges.

Because the Moon passes just inside the umbra, totality will be very short and the Moon's southern edge, in particular, should remain fairly bright. After only 25 minutes the leading edge of the Moon will emerge back into sunlight, and the eclipse is again partial. In another hour and 33 minutes the last of the Moon emerges out of the umbra.

Details about this event, and the solar eclipse visible from Antarctica, Australia, and New Zealand on November 23–24, appear in the November 2003 issue of Sky & Telescope magazine.

The next total eclipse of the Moon falls on May 4–5, 2004, and is visible from central and south Asia, the Middle East, and the eastern two-thirds of Africa. North Americans will see their next lunar eclipse on October 27–28, 2004.

November's astronomical highlights also include the Leonid meteor shower. After five consecutive years of intense, even storm-level displays, the shower should return to normal activity in 2003. That means no more than 10 to 20 meteors per hour under the best of conditions before dawn on Tuesday, November 18th. Complicating the picture, a bright last-quarter Moon will be high in the sky.

Despite their low numbers, the Leonids tend to be bright and leave persistent trains. For a report on last year's shower, see our online article "Leonids '02: A Sprinkle in the Moonlight". For general information about meteors, see SkyandTelescope.com's Meteors page.

Sky & Telescope is making two illustrations, two photographs, and one animation available to editors and producers. Permission is granted for one-time, nonexclusive use in print and broadcast media, as long as appropriate credits (as noted in each caption) are included. Web publication must include a link to SkyandTelescope.com.

A lunar eclipse occurs when the Moon passes through the shadow cast by the sunlit Earth. Like any shadow, it has two components: the outer, lighter penumbra and the inner, much darker umbra. When the Moon enters the penumbra, where just part of the Sun's light is blocked, it becomes only slightly dimmer. Only when it passes into the umbra does it look markedly different. But even when completely within the umbra, the Moon does not disappear altogether. Sunlight skims through the Earth's atmosphere and is refracted (bent) into the shadow, casting a reddish tinge upon the lunar surface. The diagram is not to scale. Click on the image to download a publication-quality JPEG (399 kilobytes) by FTP; the illustration is also available without labels (344 kilobytes).

Sky & Telescope illustration by Gregg Dinderman.

A lunar eclipse occurs when the Moon passes through the shadow cast by the sunlit Earth. Like any shadow, it has two components: the outer, lighter penumbra and the inner, much darker umbra. When the Moon enters the penumbra, it becomes only slightly dimmer. Only when it passes into the umbra does it look markedly different. On the night of November 8–9, 2003, the Moon crosses barely inside the southern part of the umbra, so even during totality the Moon's southern edge will likely appear fairly bright. Click on the image to download a publication-quality JPEG (503 kilobytes) by FTP; the illustration is also available without labels (300 kilobytes).

Sky & Telescope illustration by Steven Simpson.

On November 18-19, 1975, Sky & Telescope's Dennis di Cicco captured this image of the totally eclipsed Moon. Totality on November 8-9, 2003, may look a lot like this, as the geometries of the 1975 and 2003 eclipses are similar. Click on the image to download a publication-quality JPEG (3.4 megabytes) by FTP.

Sky & Telescope photograph by Dennis di Cicco.

Aligning his camera on the same star for nine successive exposures, Sky & Telescope contributing photographer Akira Fujii captured this record of the Moon’s progress dead center through the Earth’s shadow in July 2000. On November 8–9, 2003, another total lunar eclipse will be visible from North America. Click on the image to download a publication-quality JPEG (1.5 megabytes) by FTP.

Courtesy Akira Fujii and Sky & Telescope.

This 10-second animation of a total lunar eclipse consists of 291 black-and-white images taken on September 27, 1996. In this sequence, 1 second represents 30 minutes of elapsed time. Coloring has been added to simulate the Moon's appearance when it was completely within Earth's shadow; the totally eclipsed Moon has been brightened for clarity. During totality, dark, murky blobs are seen crossing the lunar disk — an effect caused by variations in the tiny amount of sunlight that leaks onto the Moon after being refracted (bent) through Earth's atmosphere. This can be viewed or downloaded by FTP as a broadcast-quality (3.7-megabyte) QuickTime animation.

Sky & Telescope animation by Craig M. Utter and Gregg Dinderman; images courtesy António Cidadão.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.