Imaging from Puerto Rico with a 12-inch telescope, Efrain Morales Rivera captured the supernova in M101 on August 29th when the outburst was still 12th magnitude. North is to the right.

Efrain Morales Rivera

The M101 supernova is still near its peak. Supernova 2011fe, which erupted in the nearby galaxy M101 three weeks ago, peaked out at about magnitude 9.9 for a week and is now barely starting to fade; it was 10.2 on the evening of September 19th. See an up-to-date light curve.

You'll almost certainly be using the supernova to find M101, not the other way around; the galaxy (off the handle of the Big Dipper) is diffuse and easily wiped out by any skyglow. To identify which tiny speck is the supernova, use the comparison-star charts that you can generate courtesy of the American Association of Variable Star Observers. Enter the star name SN 2011fe, and choose the "predefined chart scales" A, B, and C. Print out all three. The two brightest stars on the "A" chart are the last two stars in the the Big Dipper's handle.

This is the brightest supernova that's been visible from mid-northern latitudes in three decades. It's well within visual reach of a 4-inch scope. Although it looks like an ordinary star, it's at least 1,000 times more distant than any other star that's visible in amateur telescopes from northern latitudes. See our article, The M101 Supernova Shines On.

Friday, Sept. 16

Saturday, Sept. 17

Sunday, Sept. 18

Monday, Sept. 19

Tuesday, Sept. 20

Wednesday, Sept. 21

The waning Moon passes Mars and Regulus in the early hours of the morning.

Sky & Telescope diagram

Thursday, Sept. 22

Friday, Sept. 23

Saturday, Sept. 24

Want to become a better amateur astronomer? Learn your way around the constellations. They're the key to locating everything fainter and deeper to hunt with binoculars or a telescope.

For an easy-to-use constellation guide covering the whole evening sky, use the big monthly map in the center of each issue of Sky & Telescope, the essential magazine of astronomy. Or download our free Getting Started in Astronomy booklet (which only has bimonthly maps).

The Pocket Sky Atlas plots 30,796 stars to magnitude 7.6 — which may sound like a lot, but that's less than one star in an entire telescopic field of view, on average. By comparison, Sky Atlas 2000.0 plots 81,312 stars to magnitude 8.5, typically one or two stars per telescopic field. Both atlases include many hundreds of deep-sky targets — galaxies, star clusters, and nebulae — to hunt among the stars.

Sky & Telescope

Once you get a telescope, to put it to good use you must have a detailed, large-scale sky atlas (set of charts). The standards are the Pocket Sky Atlas, which shows stars to magnitude 7.6; the larger Sky Atlas 2000.0 (stars to magnitude 8.5); and the even larger and deeper Uranometria 2000.0 (stars to magnitude 9.75). And read how to use sky charts effectively.

You'll also want a good deep-sky guidebook, such as Sue French's new Deep-Sky Wonders collection, Sky Atlas 2000.0 Companion by Strong and Sinnott, the bigger Night Sky Observer's Guide by Kepple and Sanner, or the classic if dated Burnham's Celestial Handbook.

Can a computerized telescope take their place? I don't think so — not for beginners, anyway, and especially not on mounts that are less than top-quality mechanically. As Terence Dickinson and Alan Dyer say in their Backyard Astronomer's Guide, "A full appreciation of the universe cannot come without developing the skills to find things in the sky and understanding how the sky works. This knowledge comes only by spending time under the stars with star maps in hand."

This Week's Planet Roundup

With a diameter of only 4.9 arcseconds, Mars certainly isn't much to look at in a telescope by eye. But stacked-video imaging can work magic. On the morning of September 13th, Sky & Telescope's imaging editor Sean Walker assembled this shot using a 12.5-inch Newtonian reflector at f/44, a DMK 21AU618.AS video camera, and Astrodon RGB filters.

South is up; note the north polar cloud hood at bottom. The brighter, sharper North Polar Cap should be emerging into view as the cloud hood clears off in coming weeks. The large, darkest diagonal mark near top is Mare Cimmerium. Near the center of the disk, bright Elysium is surrounded by dark features

S&T: Sean Walker

Mercury (about magnitude –1.5) is sinking down deep into the glow of sunrise. Early in the week you can try looking for it low in the east about 30 minutes before sunup. Binoculars help. It's very far below or lower left of Mars, Castor, and Pollux. Don't confuse it with twinkly Regulus, well to its upper right.

(To find your local time of sunrise, you can use our online almanac for your location. If you're on daylight saving time, make sure the Daylight Saving Time box is checked.)

Venus (magnitude –3.9) may be catchable in binoculars just above the horizon due west a mere 15 minutes after sunset. Good luck. If you detect it, you'll be one of a very select few to pick up Venus this early in its new apparition — compared to the billions of people who will see it as the Evening Star blazing in twilight as it moves higher in the coming months.

Mars (magnitude +1.3, crossing from Gemini into Cancer) rises around 2 a.m. daylight saving time. By the beginning of dawn it's in good view high in the east, below or lower right of Castor and Pollux. Farther right of Mars is Procyon. Much farther lower right of Procyon shines bright Sirius. In a telescope, Mars is a tiny blob only 5 arcseconds wide.

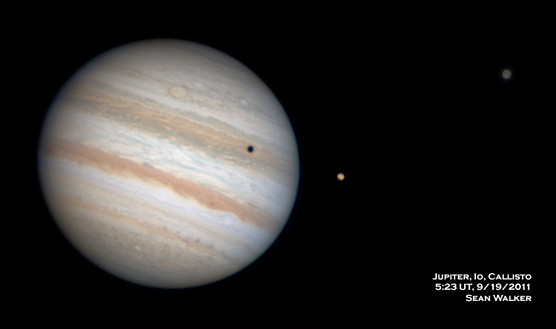

Jupiter (magnitude –2.8, in southern Aries) rises in the east-northeast around the end of twilight. Look above it for the stars of Aries and (once Jupiter is well up) closer below it for the head of Cetus, rather dim. Jupiter shines highest in the south in the hours before dawn, making this the best time to examine it with a telescope. It's now a big 47 arcseconds wide.

Io and darker Callisto were just east of Jupiter when S&T's Sean Walker imaged the scene on the morning of September 19th. South is up. Note the reddish Oval BA, "Red Spot Junior," just past the central meridian in the South Temperate Belt. Walker made this stacked-video image with the same telescope and setup as for the Mars image above.

S&T: Sean Walker

Saturn (magnitude +0.9) is disappearing for the season. Use binoculars to search for it low above the western horizon in bright twilight after sunset (upper left of even-lower Venus). Left of Saturn by 8°, look for Spica twinkling vigorously.

Uranus (magnitude 5.7, in Pisces) and Neptune (magnitude 7.8, in Aquarius) are well placed in the south and southeast by mid- to late evening. Use our printable finder chart for both, or see the September Sky & Telescope, page 53.

All descriptions that relate to your horizon — including the words up, down, right, and left — are written for the world's mid-northern latitudes. Descriptions that also depend on longitude (mainly Moon positions) are for North America. Eastern Daylight Time (EDT) equals Universal Time (also known as UT, UTC, or GMT) minus 4 hours.

NEW BOOK: Sue French's DEEP-SKY WONDERS! This long-awaited observing guide by Sky & Telescope's own Sue French is now available for pre-order from Shop at Sky. Big and lavishly illustrated, it contains Sue’s 100 favorite sky tours (25 per season) from her 11 years of writing the Celestial Sampler and Deep-Sky Wonders columns for S&T. Pre-order now and your book will ship on September 26th. Don’t miss it!

To be sure to get the current Sky at a Glance, bookmark this URL:

http://SkyandTelescope.com/observing/ataglance?1=1

If pictures fail to load, refresh the page. If they still fail to load, change the 1 at the end of the URL to any other character and try again.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.