Our solar system’s biggest planet is a captivating sight. Learn how to see Jupiter with your binoculars or telescope.

What's your favorite planet?

If it's Mars, you certainly have lots of company. The fascination with the Red Planet as a possible abode of life goes back well over a century. Or perhaps you're fondest of Saturn. Nothing compares to those wonderful rings.

Sean Walker

For me, however, it's Jupiter. What makes Jupiter such a treat is that it offers more to see in a telescope than any other planet. It's the only one that shows distinct features in even a fairly small scope. And it's got four large moons that hover nearby like bright fireflies, forever shuttling back and forth around Jupiter's glaring globe.

How to See Jupiter with Binoculars

Jupiter was king of the gods in Roman mythology, and when it's high in the sky, it rules unchallenged as the brightest "star" in the sky.

Before you track down this planet with your telescope, grab your binoculars and find a tree or wall to brace against while pointing them toward Jupiter. If your binoculars are good quality and magnify at least seven times (they'll be marked 7×35 or 7×50, for example), you'll see Jupiter as a tiny white disk.

Look closely to either side of Jupiter's disk — do you see a line of three or four tiny stars? Each of these is a satellite of Jupiter roughly the size of our own Moon. They only look tiny and faint because they're about 2,000 times farther away.

Hide-and-Seek Moons

Now put a low-power eyepiece in your telescope and center Jupiter. Focus carefully so that the planet's edge is as sharp as possible, let any vibrations settle down, and then take a good long look.

Sky & Telescope illustration

Depending on the size of your scope and the quality of the night's seeing, you'll see something like the view here. Now the moons are much more obvious. You'll probably see all four — but possibly only three depending on when you look. The count often changes from night to night (or if you're patient, even from hour to hour). That's because while orbiting Jupiter they sometimes glide in front of the planet, behind it, or through its shadow.

These hide-and-seek movements confounded Galileo Galilei when he first spied these "stars" in 1610. But he soon realized they were actually circling around Jupiter, forming a miniature solar system of sorts. We see their orbits almost exactly edge on.

The four are named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto — or, collectively, the Galilean satellites — and it's hard to tell which is which just by looking. Callisto is usually (but not always) farthest from Jupiter, and Ganymede is a little brighter than the others. Sulfur-coated Io has a pale yellow-orange cast. Still not sure? The answers are just a mouse clicks away, thanks to Sky & Telescope's handy guide to identifying the Galilean satellites at any time and date.

Earning Your Stripes

Now turn your attention to see Jupiter itself. Center its round disk in the middle of your telescope's view, then carefully switch to a higher-power eyepiece and refocus. Study the disk closely, and two things should be noticeable. First, the disk is not perfectly round. Among the planets, Jupiter has the fastest spin (once every 10 hours), rotating so quickly that its equatorial midsection bulges out a bit. It's 7% wider across the equator than from pole to pole.

Jupiter is a gas giant planet — it consists almost entirely of hydrogen and helium, nearly all the way down. The "surface" you see is actually the top layers of cloud decks floating near the top of an immensely deep atmosphere.

Anthony Wesley

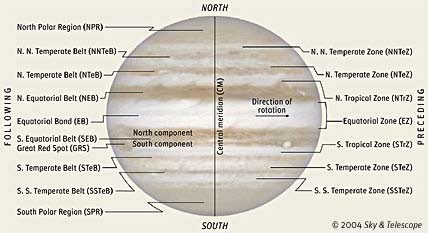

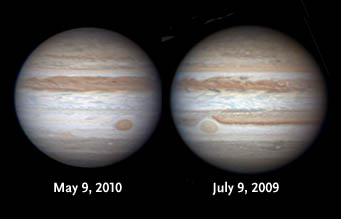

Look for at least two tawny-colored stripes running parallel to the equator. These darkish cloud bands are called belts, and the brighter cloud areas between them are called zones. The North and South Equatorial Belts, usually the most prominent, straddle the bright Equatorial Zone like a cream-filled cookie sandwich. If you're using at least a 6-inch telescope, you may be able to pick out a few belts and zones closer to Jupiter's poles.

The single most famous cloud feature on Jupiter is the Great Red Spot, an enormous, oval-shaped storm about twice the size of Earth. Astronomers have observed the Red Spot for at least 150 years, but there's still no agreement on what chemical compounds create its distinctive color. Like any big storm, the spot changes appearance over time. The intensity of its color has sometimes been brick red (very rarely), pale orange tan (more often), pinkish tan, or an almost invisible creamy yellowish. Changes usually happen over a year or two.

When the spot is so pale as to be invisible, you may be able to identify it indirectly by noting the indentation it makes in the south edge of the South Equatorial Belt: a feature dubbed the "Red Spot Hollow."

Be forewarned that seeing the Great Red Spot is a challenge in a small telescope. Your best prospects will be when the spot appears near the middle of Jupiter's disk — Sky & Telescope's online calculator helps you know when to look. The planet's rapid rotation means that these windows of opportunity last only a couple hours, so be prepared to search for the spot over several consecutive nights.

No matter how you look at it, Jupiter is so easy to see that it makes an irresistible telescopic target anytime it's visible in the night sky — and that's why it's my favorite planet.

7

7

Comments

Chris Schur

January 6, 2014 at 9:20 am

Very nice image Sean! Lots of wind in Arizona last night, could not even resolve the largest moon Ganymede. Noramlly with our 12 inch we can usually see the polar caps on this moon. Maybe tonight...

Chris

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Hope

January 9, 2014 at 1:50 pm

Hi,

Where to spot Jupiter in the southern hemisphere.

Thx

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Thanassis

January 11, 2014 at 1:46 am

Very informative article, I liked the stripes image. Also Jupiter comes Greek mythology and not Roman.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Mike Lynch

February 6, 2014 at 2:45 pm

Yes, I'm sure the cloud-tops of Jupiter truly are a sight to see...but the cloud-bottoms here on Earth (over Kentucky, at least!) are making Jove's features impossible to see!! Blaming our neighborhood groundhog!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Jeff

October 6, 2021 at 11:39 pm

Great article! As a late-comer to the site, I attempted to use the online calculator to find the best date/time to see the Great Red Spot. The link sent me to a broken/missing web page 🙁 Maybe a web master at S&T can fix that.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

J. Kelly BeattyPost Author

October 7, 2021 at 11:19 am

Jeff . . . thanks for pointing out that dead link. now fixed! so please try again.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.