Choose the telescope that’s right for your observing interests, lifestyle, and budget.

Craig Michael Utter / Sky & Telescope

A telescope is a popular gift, especially so during the holidays. It can be a portal to the universe and provide a lifetime of enjoyment.

But there's no one "perfect" telescope — just as there's no such thing as a perfect car. Instead, you should choose a telescope based on your observing interests, lifestyle, and budget. Many (arguably most) good starter scopes cost $400 or more, though some superb choices are available for under $250.

So here is a guide to help you make sense of the "universe" of telescope models available today. Armed with these few basic types of telescopes, you'll have a good idea what to look for (and what to avoid) when scouring the marketplace for your new scope. Get the one that's right for you!

The telescope you want has two essentials: high-quality optics and a steady, smoothly working mount. And all other things being equal, big scopes show more and are easier to use than small ones, as we'll see below. But don't overlook portability and convenience — the best scope for you is the one you'll actually use.

Aperture: A Telescope's Most Important Feature

The most important characteristic of a telescope is its aperture — the diameter of its light-gathering lens or mirror, often called the objective. Look for the telescope's specifications near its focuser, at the front of the tube, or on the box. The aperture's diameter (D) will be expressed either in millimeters or, less commonly, in inches (1 inch equals 25.4 mm). As a rule of thumb, your telescope should have at least 2.8 inches (70 mm) aperture — and preferably more.

Craig Michael Utter / Sky & Telescope

A larger aperture lets you see fainter objects and finer detail than a smaller one can. But a good small scope can still show you plenty — especially if you live far from city lights. For example, from a dark location you can spot dozens of galaxies beyond our own Milky Way through a scope with an aperture of 80 mm (3.1 inches). But you'd probably need a 6- or 8-inch telescope (like the one shown at right) to see those same galaxies from a typical suburban backyard. And regardless of how bright or dark your skies are, the view through a telescope with plenty of aperture is more impressive than the view of the same object through a smaller scope.

Avoid telescopes that are advertised by their magnification — especially implausibly high powers like 600×. For most purposes, a telescope's maximum useful magnification is 50 times its aperture in inches (or twice its aperture in millimeters) . So you'd need a 12-inch-wide scope to get a decent image at 600×. And even then, you'd need to wait for a night when the observing conditions are perfect.

Types of Telescopes

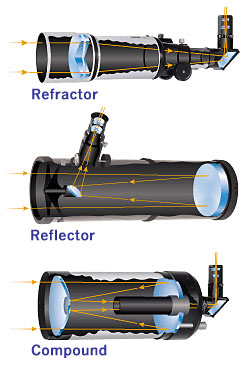

You'll encounter three basic types of telescopes:

Gregg Dinderman / Sky & Telescope

- Refractors have a lens at the front of the tube — it's the type you're probably most familiar with. While generally low maintenance, they quickly get expensive as the aperture increases. In refractor lingo, an apochromat offers better optical quality (and is more expensive) than an achromat of the same size. Watch an animation of light passing through a refractor.

- Reflectors gather light using a mirror at the rear of the main tube. For a given aperture, these are generally the least expensive type, but you'll need to adjust the optical alignment every now and then — more often if you bump it around a lot — but that adjustment (called collimation) is straightforward. Watch an animation of light passing through a reflector.

- Compound (or catadioptric) telescopes, which use a combination of lenses and mirrors, offer compact tubes and relatively light weight; two popular designs you'll often see are called Schmidt-Cassegrains and Maksutov-Cassegrains. Watch an animation of light passing through a compound telescope.

The objective's focal length (F or FL) is the key to determining the telescope's magnification ("power"). This is simply the objective's focal length divided by that of the eyepiece, which you'll find on its barrel. For example, if a telescope has a focal length of 500 mm and a 25-mm eyepiece, then the magnification is 500/25, or 20×. Most types of telescopes come supplied with one or two eyepieces; you change the magnification by switching eyepieces with different focal lengths.

The Mount: A Telescope's Most Under-Appreciated Asset

Your telescope will need something sturdy to support it. Many telescopes come conveniently packaged with tripods or mounts, though the tubes of some smaller scopes often just have a mounting block that allows them to be attached to a standard photo tripod with a single screw. (Caution: A tripod that's good enough for taking your family snapshots may not be steady enough for astronomy.) Mounts designed specifically for telescopes usually forgo the single-screw attachment blocks in favor of larger, more robust rings or plates.

Craig Michael Utter / Sky & Telescope

On some mounts the scope swings left and right, up and down, just as it would on a photo tripod; these are known as altitude-azimuth (or simply alt-az) mounts. Many reflectors come on an elegantly simple wooden platform, known as a Dobsonian, that's a variation of the alt-az mount. A more involved mechanism, designed to track the motion of the stars by turning on a single axis, is termed an equatorial mount. These tend to be larger and heavier than alt-az designs; to use an equatorial mount properly you'll also need to align it to Polaris, the North Star.

Some telescopes come with small motors to move them around the sky with the push of a keypad button. In the more advanced models of this type, often called "Go To" telescopes, a small computer is built into the hand control. Once you've entered the current date, time, and your location (and many newer models don't even require you to do that), the scope can point itself to, and track, thousands of celestial objects. Some "Go To"s let you choose a guided tour of the best celestial showpieces, complete with a digital readout describing what's known about each object.

But Go To scopes aren't for everyone — the setup process may be confusing if you don't know how to find the bright alignment stars in the sky. And lower-priced Go To models come with smaller apertures than similarly priced, entry-level scopes that have no electronics.

Remember . . .

Any telescope can literally open your eyes to a universe of celestial delights. With a little care in selecting the right type of telescope for you, you'll be ready for a lifetime of exploring the night sky!

If you still have questions or need more details, check out these additional resources:

- Detailed advice for choosing a telescope (online article)

- "What to Know Before You Buy" (PDF) from SkyWatch 2010

- Comparative review of three telescopes (PDF), each around $200

- Subscribe to Sky & Telescope

9

9

Comments

November 23, 2015 at 4:42 pm

"Aperture: A Telescope's Most Important Feature" Those three little paragraphs cleared up a lot questions and confusion I had.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Ramon-Casha

November 27, 2015 at 10:48 am

I would just add that the above apply mostly for visual observing. For astrophotography, the aperture is less important since you can make up for it with a long exposure, but you need a really good equatorial mount. It's common for a mount to cost more than the telescope on it.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Tony Flanders

September 20, 2020 at 7:59 am

This is a good point. Many beginners expect to do astrophotography right off the bat. The article should probably make it clear that although astrophotography is much easier than ever before, it is still not easy. And that it places much greater emphasis on the mount.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Philip-Sherman

November 30, 2015 at 11:03 pm

I believe that there's one additional factor that should always be considered: the capabilities of the intended recipient. I faced this factor last year when I decided to buy a first telescope for my 8-year old granddaughter. I ended up buying her a 76mm tabletop Dobsonian scope because this was one that she could carry in and out of the house herself and, when set on the back yard table, had the eyepiece at an appropriate height for her.

This scope was bought with the following rule in mind: The scope that gets used regularly is always a better scope than the one that rarely or never gets used.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

December 19, 2016 at 4:02 am

Great article. I wanted to mention that I picked up a 3" refractor with an alt-az mount at a thrift store for around $12 recently. The mount is collapsible, making it a great choice for a camping trip into the mountains (next summer). The store had a small reflector for $40 that I passed on.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

ajc

January 10, 2017 at 5:37 pm

“As a rule of thumb, your telescope should have at least 2.8 inches (70 mm) aperture — and preferably more.”

I can not agree with that. A 60mm F / 13 can be very useful in lunar and planetary observation.

“The most important characteristic of a telescope is its aperture”

Why? To observe variable stars, Moon and planets, in an urban sky, is an 85mm ED worse than a 114mm reflector?

These statements are disappointing. I expected something better.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Rcellison

April 21, 2017 at 2:17 pm

It's for beginners... that makes no sense to someone like myself who is just starting out.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Tony Flanders

September 20, 2020 at 8:08 am

A rule of thumb is not meant to take every possible exception and nuance into account. There is no doubt that 60-mm telescopes can be useful. But for the average beginner, a 70-mm scope (or bigger) is a much smarter choice.

Having said that, the article possibly should mention that refractors generally have somewhat higher performance per unit of aperture than reflectors or cats. Sadly, explaining precisely why that's true would make the article much longer, and brevity is this article's greatest strength.

To answer the question posed here, an 85-mm ED refractor is indeed worse than a 114-mm reflector of comparable quality, though not by as big a margin as the apertures would suggest.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

selnomeria

October 16, 2020 at 6:11 am

Let say telescope: 25mm(D=eyepiece)/500mm(F)

A) Magnification will be 500/25=20x

B) Maximum magnification is around 2 times of it's D, so 25x2 = 50x ?

Is this correct what I understood? So, could you describe difference between Magnification VS MAXIMUM MAGNIFICATION ?

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.